The Quiet Rebellion of Hands That Need Something Real

There’s a particular kind of exhaustion that settles in after eight hours of screens. Not physical tiredness—more like a low-grade sensory deprivation. Your eyes have tracked thousands of pixels. Your fingers have tapped glass surfaces countless times. And somewhere in your brain, a small voice whispers: I haven’t actually touched anything today.

This isn’t new. Psychologists have studied the disconnect between digital interaction and tactile engagement for decades. But the cultural response is relatively recent: a surge of interest in objects that demand physical manipulation. Mechanical keyboards. Vinyl records. And, quietly, a resurgence of interlocking puzzles that date back centuries.

The puzzle toy category has seen renewed interest not because people suddenly care about brain training—though that’s a convenient narrative—but because hands remember what fingers have forgotten. There’s something grounding about an object that resists you, that requires rotation and pressure and patience before it yields.

Which brings us to a peculiar item: twelve miniature transparent puzzles, each designed around principles that predate electricity by roughly two millennia.

First Contact: Unboxing Twelve Tiny Engineering Marvels

The 12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set arrives without ceremony. Depending on packaging variants, you’ll find either a small box or a pouch containing a dozen acrylic puzzles, each roughly the size of a large grape or small walnut. Sizes range from 3.7cm to 5.5cm across. Weights span 5 grams to 12.8 grams per unit.

First impression: they’re lighter than expected. Wood has heft. Metal has presence. Acrylic has something closer to deliberate insubstantiality—like the material is trying not to interrupt your fingers.

The surfaces are smooth, almost slick. Each puzzle catches light differently depending on its color: translucent blues, greens, oranges, and pinks. The transparency isn’t cosmetic; it’s functional. You can see inside. Every notch, every protrusion, every interlocking geometry is visible through the acrylic walls.

This should make solving easier. It doesn’t.

The set includes twelve distinct mechanisms:

- 三通锁 (3-Piece Burr / T-Lock): 5×5cm, 5g

- 六片拼 (Six-Piece Burr / Chinese Cross): 4.7×4.7cm, 6.5g

- 鲁班球 (Luban Ball / Sphere Lock): 4.3×4.3cm, 9.2g

- 足球锁 (Football Lock / Soccer Ball): 4.5×4.5cm, 12.8g

- 潜伏 (Stealth Cube / Hidden Puzzle): 4.8×4.8cm, 8g

- 六根 (Six-Stick Cross / Traditional Burr): 4.7×4.7cm, 6.5g

- 墙角 (Corner Lock / L-Shape): 3.7×3.7cm, 8g

- 好汉锁 (Hero Lock / Cross Burr): 4.7×4.7cm, 6.5g

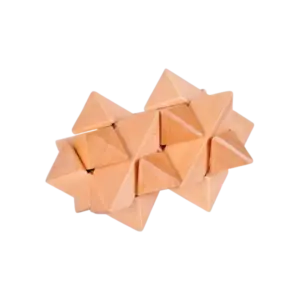

- 六方宝石 (Star Puzzle / 6-Point Crystal): 4.5×4.5cm, 9.5g

- 卫星锁 (Satellite Lock / Orbit Puzzle): 5.5×5.5cm, 7.2g

- 心心相印 (Heart to Heart / Dual Heart Lock): 4.2×4.2cm, 10.5g

- 太极锁 (Yin Yang Lock / Tai Chi Ball): 4.5×4.5cm, 7.5g

Each uses a different interlocking strategy. Some are straightforward once you understand the sequence. Others will occupy your desk for days.

The category these belong to—plastic puzzles—tends to get overlooked by enthusiasts who prefer the tactile warmth of wood or the satisfying weight of metal. That’s a mistake. Acrylic has its own merits: durability, precision molding, and—crucially—the ability to reveal internal structures without disassembly.

The Tactile Reality

Pick up the Luban Ball (鲁班球) first. It’s roughly 4.3cm across—fits in the palm without crowding. The acrylic feels cool initially, warming slightly as you manipulate it. The surface is slick but not slippery; your fingers maintain grip during rotation.

Now try to pull it apart.

The pieces resist. Not through friction alone—though that’s present—but through geometric interference. Curves interlock with curves. Press in one direction and something else blocks. The mechanism is visible through the transparent walls, yet the solution remains opaque.

This is the experience repeated across all twelve puzzles, with variations in geometry and difficulty.

The Corner Lock (墙角) is the smallest at 3.7×3.7cm. It fits between thumb and forefinger, almost delicate. The L-shape configuration makes it one of the more approachable designs, but “approachable” doesn’t mean “trivial.” New users often attempt intuitive approaches—twisting, pulling, applying force—before discovering that the pieces only separate through specific sequential movements.

The Football Lock (足球锁), by contrast, fills the palm. At 12.8 grams, it’s the heaviest piece in the set, though still remarkably light compared to equivalent wood or metal puzzles. The hexagonal and pentagonal facets catch light differently as you rotate, creating a subtle visual play that wooden puzzles can’t replicate.

Sound and Silence

Wooden interlocking puzzles produce satisfying acoustic feedback: clicks, slides, subtle wooden taps. Metal puzzles ring and clank.

Acrylic is quiet. The sound profile is closer to plastic on plastic—a soft shush when pieces slide, a muted tap when they lock. For some users, this is a deficit; acoustic feedback helps confirm correct movements. For others—particularly those solving puzzles in shared workspaces—the silence is a feature.

The satisfying moment isn’t auditory. It’s haptic: the feeling when resistance suddenly disappears because pieces have aligned correctly, or when previously mobile components lock into rigid stillness because the key piece has rotated into position.

The Transparency Paradox: Why Seeing Everything Helps Nothing

Here’s what happens when most people encounter a transparent puzzle for the first time.

They pick it up. They rotate it. They observe the internal grooves and protrusions. They think: I can see exactly how this works. This should take thirty seconds.

Twenty minutes later, they’re still holding the same puzzle, increasingly frustrated.

The transparency paradox is a real phenomenon in interlocking puzzle communities. Visibility creates an illusion of understanding. You can see the notches. You can trace where pieces should slide. But mechanical puzzles aren’t about seeing—they’re about sequence. The order of operations matters more than the final configuration.

Consider the 六片拼 (Six-Piece Burr). This is the classic design, documented in puzzle literature since at least 1893 when it appeared in Hoffmann’s Puzzles Old and New as “The Nut Puzzle.” According to Wikipedia’s documentation on burr puzzles, the six-piece variant can theoretically be assembled in over 35 billion configurations—though only a fraction actually work.

You can see all six pieces inside the crystal version. You can identify the key piece (the one that rotates to lock or unlock the structure). You can observe the exact shape of every notch.

None of this tells you which piece to move first. Or second. Or third.

Friction points observed in this set:

- Sequence blindness: The correct assembly order isn’t intuitive from visual inspection

- Piece identification: After disassembly, remembering which piece came from which puzzle becomes challenging

- Tolerance variations: Some puzzles slide smoothly; others require precise alignment before pieces will move

- No included solutions: You’ll need external resources (online videos, guides) to solve the harder variants

Mitigations that work:

- Photograph each puzzle before disassembly

- Work one puzzle at a time—never mix pieces from different locks

- If a piece won’t slide, don’t force it; re-check alignment

- Tea-Sip’s six-piece burr puzzle guide covers the classic design in detail

The Mechanical Soul: 2,500 Years of Engineering in Your Palm

The term “Luban lock” (鲁班锁) refers to a legendary Chinese carpenter named Lu Ban, who lived around 507–440 BCE during the Spring and Autumn period. Whether Lu Ban actually invented these puzzles is historically uncertain, but his association with them speaks to the deep connection between interlocking puzzles and traditional Chinese woodworking.

The principle underlying every puzzle in this set is mortise-and-tenon joinery—a structural technique that predates written history. According to research published by NC State’s BioResources journal, mortise-and-tenon structures “utilize the natural friction of wood to create tight joints that prevent warping and loosening.” The same research notes that this joinery technique has been recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage.

What makes this relevant to a set of acrylic toys?

The crystal Luban locks translate wood joinery principles into a different material while preserving the core mechanical logic. Each puzzle relies on:

- Friction between mating surfaces: Pieces stay together because surfaces contact with enough resistance to hold position

- Geometric interference: Notches and protrusions create physical barriers that prevent incorrect assembly

- Sequential dependence: Each piece can only be inserted or removed in a specific order

The transition from wood to acrylic changes the tactile experience—smoother slides, less acoustic feedback—but the mechanical principles remain identical to puzzles built centuries ago.

For those interested in how these designs evolved, Tea-Sip’s blog covers historical context alongside solving strategies.

Flow, Frustration, and the Space Between

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist who pioneered research on flow states, observed artists becoming so absorbed in their work that they ignored basic needs like food and sleep. His subjects described the experience through metaphors of being carried by a current—hence the term “flow.” According to the University of Chicago’s memorial for Csikszentmihalyi, his research demonstrated that “happiness is an internal state of being” achieved through activities that balance skill and challenge.

The 12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set occupies an interesting position on Csikszentmihalyi’s skill-challenge model.

When the challenge exceeds your skill—common during initial attempts with harder puzzles like the Luban Ball or Star Puzzle—you experience anxiety or frustration. When your skill exceeds the challenge—after solving the simpler locks multiple times—you drift toward boredom.

Flow occurs in the narrow band between: when you’re working on a puzzle just difficult enough to demand attention but not so difficult that progress feels impossible.

The set’s variety helps here. Twelve puzzles means twelve different difficulty levels. The 3-Piece Burr and Corner Lock are approachable for beginners. The Football Lock and Yin Yang Lock will frustrate experienced puzzlers. This range allows you to self-select challenges appropriate to your current skill level.

I should be clear: there is no medical or therapeutic claim here. Flow isn’t a treatment. But the experience of focused engagement—hands occupied, attention narrowed, time perception altered—is something these puzzles consistently produce.

Physics in Miniature: How These Actually Work

Let’s get specific about mechanisms.

The Key Piece Principle

Most puzzles in this set use a “key piece”—a component that, when correctly positioned, locks or unlocks the entire structure. In the Six-Piece Burr, the key is typically an unnotched stick that slides in last. Rotation of this piece in one direction locks everything tight; rotation in the opposite direction allows disassembly.

The key piece works because of geometric interference. When oriented correctly, its surfaces contact adjacent pieces in ways that prevent movement. When rotated, contact points shift, and previously locked pieces gain freedom to slide.

Friction Coefficients and Tolerance

Acrylic-on-acrylic friction is lower than wood-on-wood. This means crystal Luban locks slide more freely once pieces are correctly aligned—but also means they’re less forgiving of slight misalignment. Where a wooden puzzle might allow a slightly incorrect piece position to “stick” through friction, acrylic pieces either fit precisely or won’t fit at all.

Research on traditional mortise-and-tenon joints confirms that friction is the primary holding force in nail-free joinery. The same BioResources study cited earlier describes how “functionally, [mortise and tenon] utilizes the natural friction of wood to create tight joints.”

In acrylic, this friction is reduced but still operative. The puzzles hold together through a combination of friction and geometric trapping—pieces that physically cannot move because other pieces block their path.

The Mathematics of Impossibility

Here’s where burr puzzles become genuinely fascinating from an engineering perspective.

Mathematician Bill Cutler conducted an exhaustive computer analysis of six-piece burr possibilities in the late 1970s. His work, later discussed by Martin Gardner in Scientific American, revealed staggering numbers: there are 837 usable pieces that could be made using standard notch configurations. These pieces can theoretically combine to create over 35 billion possible assemblies—though only a fraction represent actual solvable puzzles.

The six-piece burr in this crystal set represents one of those valid configurations. Every notch placement, every protrusion depth, has been calculated to allow exactly one assembly sequence. The transparent material lets you see this precision engineering, even if you can’t immediately comprehend it.

Why Traditional Joinery Survived Earthquakes

The connection between Luban locks and Chinese architecture isn’t merely symbolic. Research on traditional timber frame structures has demonstrated that mortise-and-tenon joinery provides exceptional seismic resilience. Studies published in BioResources document how these joints allow controlled movement during seismic events—flexing rather than breaking.

The same principles apply to the puzzles in your hand. The pieces can move within their tolerances, absorbing minor impacts without damage. Drop a crystal Luban lock and the pieces might separate—but they won’t shatter like rigid ceramic or bend like soft plastic. The interlocking geometry distributes force across multiple contact points.

This durability is why these designs persist. Lu Ban’s joinery principles have been tested by millennia of practical use. The crystal versions inherit that mechanical robustness, translated into modern materials.

Curved Geometry: The Luban Ball and Football Lock

Two puzzles in this set—the Luban Ball and Football Lock—use curved pieces. This dramatically increases difficulty.

With straight-stick puzzles, movement is constrained to linear slides along axis-aligned paths. With curved pieces, movement can involve partial rotations and arcs. The solution space expands, making the correct sequence harder to discover through trial and error.

The Football Lock (足球锁) in particular combines curve-based interlocking with soccer-ball geometry: pentagonal and hexagonal surfaces reminiscent of a truncated icosahedron. It’s the heaviest piece in the set at 12.8 grams—still remarkably light—and arguably the most visually distinctive.

Who Should Buy This (And Who Should Not)

This set works well for:

- Desk fidgeters: Something for your hands during calls or thinking time

- Puzzle collectors: Twelve distinct mechanisms in a compact, portable format

- Gift seekers: Unusual, screen-free, conversation-starting present

- Travel entertainers: Fits easily in bags; occupies time during waits

- Spatial reasoning enthusiasts: Genuine cognitive challenge without time pressure

This set may frustrate:

- Instant gratification seekers: Some puzzles take hours or days to solve

- Solitary workers without solution access: No manual included; you’ll need online resources for harder locks

- Young children: Recommended for ages 8+; some pieces are small

- Those who expect transparency to equal simplicity: It doesn’t

The wooden puzzle collection offers alternatives with more tactile warmth but less internal visibility. The metal puzzle collection provides greater weight and durability with a completely different aesthetic.

Honest Expectations: Learning Curve and Replayability

Let me set realistic expectations.

Day One: You’ll likely solve 2–4 of the easier puzzles. The 3-Piece Burr and Corner Lock are the most accessible starting points.

Week One: With patience and possibly some video guidance, 6–8 puzzles are achievable. The Six-Piece Burr variants and Hero Lock fall into this range.

Month One: The advanced puzzles—Luban Ball, Football Lock, Star Puzzle, Satellite Lock, Heart to Heart, Yin Yang Lock—may still be challenging. These reward extended engagement rather than quick wins.

Replayability is high but asymmetric. Once you’ve learned a puzzle’s sequence, reassembly becomes faster with each repetition. Eventually, you’ll solve familiar locks in seconds. But you can intentionally forget sequences (by not practicing) or challenge yourself with speed attempts.

The transparency feature affects replayability differently than opaque materials. With wooden or metal puzzles, you might forget internal structures over time. With crystal versions, the mechanisms remain visible—but sequence memory still fades, preserving some challenge on return attempts.

Comparisons Worth Making

How does this set compare to alternatives?

Against wooden Luban locks: Wood offers warmer tactile feedback, better acoustic satisfaction, and traditional aesthetics. Crystal offers visibility, modern appeal, and typically better tolerance consistency (injection molding is more precise than hand-carving). If you already own wooden versions, the crystal set provides a genuinely different experience of familiar mechanisms.

Against metal interlocking puzzles: Metal puzzles are heavier, more durable for rough handling, and often more complex in mechanism. The crystal set prioritizes visibility and portability over heft and durability. For desk use, crystal wins; for workshop or outdoor settings, metal might be more appropriate.

Against single puzzles: Buying individual puzzles allows targeted difficulty selection but increases per-puzzle cost and prevents variety-based engagement. The twelve-piece set provides a complete difficulty spectrum at a lower per-unit price point.

The Gift Consideration

This set works as a gift for specific recipients:

- Engineers and makers: People who appreciate mechanical elegance will recognize the craftsmanship

- Teenagers needing screen alternatives: Challenging enough to hold attention, portable enough for any setting

- Puzzle collectors: Fills gaps in collections, especially for those without acrylic versions

- Anxious fidgeters: Something productive for nervous hands without appearing unprofessional

It works less well for:

- Very young children: Small pieces, requires patience beyond typical toddler capacity

- Recipients who prefer instant gratification: This is a journey gift, not a destination gift

- Those who need solutions immediately: Pack an iPad alongside it, or prepare for frustration

The Verdict: Ancient Engineering for Modern Attention Spans

The 12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set is not a toy in the casual sense. It’s not something you pick up, solve once, and discard. It’s closer to a collection of mechanical koans: objects that reward attention, punish impatience, and reveal themselves gradually.

The transparency is both blessing and complication. You see everything and understand little until your hands learn what your eyes cannot teach. The variety—twelve distinct mechanisms—means the set grows with you rather than becoming obsolete after initial mastery.

For those seeking mindful diversions from screen-dominated days, this collection delivers. For those expecting quick wins and immediate satisfaction, different puzzles might suit better.

The puzzles ship worldwide via Tea-Sip’s standard process—same-day dispatch from China, typically clearing customs within a few days. Details on shipping timelines and policies are available via customer help and shipping policy pages.

Final assessment: If you appreciate mechanical elegance, have patience for sequential problem-solving, and want something your hands can work while your mind wanders or focuses—the 12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set is worth the investment.

Just don’t expect to solve them all on the first day. That’s not a flaw. That’s the point.