A Royal Commission That Changed Music Forever

In the winter of 1560, a remarkable shipment left the Italian city of Cremona bound for the French court. Inside were 38 stringed instruments, commissioned by Catherine de’ Medici as a gift for her son, King Charles IX. Among them was a peculiar bass instrument—larger than a viola, smaller than the existing bass violins—painted with royal coats of arms and Latin mottoes proclaiming “PIETATE” (piety) and “IVSTICIA” (justice).

That instrument, crafted by Andrea Amati, would become the oldest surviving cello in the world.

Today, nearly five centuries later, “The King” cello resides at the National Music Museum in South Dakota, where researchers have used CT scanning to study its construction without disturbing its fragile surfaces. The instrument tells a story not just of music, but of engineering innovation, material science, and the human drive to create objects of lasting beauty and function.

This is the story of how that innovation unfolded—and why understanding it matters more than ever in our digital age.

Part One: The Birth of an Instrument

Cremona’s Golden Age

The cello did not evolve gradually from earlier instruments. It was invented.

According to Wikipedia’s comprehensive documentation, the violoncello emerged in Northern Italy around 1530, created as part of the violin family by master craftsmen working in and around Cremona. Andrea Amati (ca. 1505–1577) is credited with establishing the form we recognize today—an instrument that combined powerful bass tones with unprecedented expressiveness.

This distinction matters historically. The cello belonged to the viola da braccio family (“for the arm”), not the viola da gamba family (“for the leg”). Though both instrument families coexisted for over two centuries, they represented different construction philosophies and playing techniques. The cello was a deliberate creation, not an accident of evolution.

The Cremona workshops operated through a master-apprentice system that would influence instrument making for generations. Andrea Amati trained his sons, who trained Nicolò Amati (1596–1684), widely considered the most influential teacher of the dynasty. Nicolò’s students included two names that would become synonymous with the finest string instruments ever made: Antonio Stradivari and Andrea Guarneri.

This chain of knowledge transmission was so significant that UNESCO designated “Cremonese traditional violin craftsmanship” as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2012. The skills passed down in those Renaissance workshops still inform how fine instruments are made today.

The Problem of Size

Early cellos faced a fundamental challenge: physics.

To produce deep bass frequencies, string instruments need length. The longer the string and the larger the resonating body, the lower the pitch. This is why bass instruments throughout history—from ancient lyres to medieval viols—tended toward massive proportions.

The original cellos were considerably larger than modern instruments. “The King” Amati cello, for instance, was modified in 1801 by luthier Sebastian Renault, who reduced its body by approximately two inches to conform to emerging performance standards. Before this modification, the instrument would have been challenging for all but the largest performers to play.

This created a tension between acoustics and ergonomics. Composers wanted bass voices in their ensembles. But musicians needed instruments they could actually hold and play for extended periods. Something had to change.

The Bologna Breakthrough

The solution came not from Cremona, but from Bologna—and it wasn’t a new instrument design. It was a new kind of string.

Around 1660, Bolognese string makers developed wire-wound strings: thin gut cores wrapped with fine metal wire. This innovation sounds simple, but its implications were revolutionary. Wire-wound strings could produce bass frequencies from shorter lengths and smaller instruments than pure gut strings. Suddenly, cellos could shrink without sacrificing their voice.

Contemporary accounts confirm Bologna’s reputation. English composer Robert Dowland noted in 1610 that “the best strings for bass instruments were made at Bologna in Lombardy.” The city became not only a center for string manufacture but also for early cello composition. Masters like Domenico Gabrielli, Giuseppe Jacchini, and Domenico Galli produced some of the first works written specifically for solo cello.

Gabrielli’s Seven Ricercare for Violoncello Solo, written in 1689, represent among the earliest solo cello compositions—predating Bach’s famous suites by nearly three decades. The term “violoncello” itself first appeared in print in 1665, in the twelve trio sonatas by Giulio Cesare Arresti, also from Bologna. The name literally means “little violone,” distinguishing it from the larger bass instruments of the era.

Part Two: Standardization and the Golden Age

Stradivari’s Revolution

Antonio Stradivari (1644–1737) did not invent the cello. But he perfected it.

Working from his Cremona workshop, Stradivari produced instruments across all sizes of the violin family. His early cellos, made before 1702, followed the larger dimensions common at the time. Only three of these survive in their original configuration.

Then, around 1707—and definitively from 1710—Stradivari began building smaller cellos. According to Britannica, these instruments featured body lengths of approximately 75–76 centimeters, widths of 44 centimeters at the bottom bout, and rib heights of 11.5 centimeters. These proportions struck an ideal balance: small enough to play comfortably, large enough to project powerfully.

The impact was immediate and dramatic. Instrument makers across Europe began converting their existing larger cellos to match Stradivari’s dimensions. This wasn’t minor modification—it involved literally sawing apart instruments and reconstructing them. The mass conversion lasted roughly a decade and left virtually no pre-17th-century cellos in their original large condition.

What drove this wholesale transformation? Performance demands. Composers were writing increasingly virtuosic music that required agility and endurance. The smaller Stradivari-style cellos made such music physically possible. Musicians who clung to larger instruments found themselves unable to execute the new repertoire.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art houses the “Batta-Piatigorsky” Stradivari cello from 1714, one of approximately 63 cellos the master produced. The instrument is occasionally featured in gallery concerts, allowing visitors to hear how these 300-year-old instruments perform music they were designed to play.

Bach and the Solo Cello

With standardized instruments and improved strings, composers began exploring what the cello could do alone.

Johann Sebastian Bach composed his six Cello Suites (BWV 1007–1012) between 1717 and 1723, during his tenure as Kapellmeister at the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. According to Wikipedia, he originally titled them Suites à Violoncello Solo senza Basso—Suites for cello solo without bass.

This was revolutionary. Previous bass instruments existed primarily to support other voices. Bach’s suites required the cello to create complete musical textures independently—melody, harmony, and rhythm from a single instrument. Each suite follows a dance structure: Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, paired dances, and Gigue. The sixth suite presents particular interest because Bach wrote it for a five-string violoncello piccolo, an instrument that has since fallen from standard use.

Music scholar Wilfrid Mellers described the suites as “monophonic music wherein a man has created a dance of God.” They remain among the most frequently performed works in the cello repertoire, studied by virtually every serious cellist.

Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805) extended these possibilities further. Beginning cello lessons with his father at age five, Boccherini made his professional debut at thirteen with a cello concerto. His technique astounded contemporaries—he could play violin repertoire on the cello at pitch, employing extensive thumb position and producing what witnesses described as a “singing tone.” He composed approximately 500 works, including the first string quintets featuring two cellos, effectively inventing a new chamber music format.

Part Three: What Building Teaches the Brain

The Science of Hands-On Learning

Here is where the cello’s story intersects with something unexpected: cognitive science.

For the past two decades, researchers have studied what happens in our brains when we engage in hands-on construction activities. The findings consistently demonstrate that building things—manipulating physical objects, solving spatial problems, creating three-dimensional structures—activates cognitive processes that passive observation cannot replicate.

A landmark study published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience (PMC6174231) examined 100 adults aged 50 and older who engaged in jigsaw puzzling for at least one hour daily over 30 days. Researchers from Ulm University found that puzzle skill showed an extremely high correlation (r = 0.80, p < 0.001) with global visuospatial cognition—the same spatial reasoning abilities that luthiers employ when shaping an instrument’s curves.

This relationship held across all eight measured cognitive abilities: perception, constructional praxis, mental rotation, processing speed, cognitive flexibility, working memory, reasoning, and episodic memory. Perhaps most significantly, lifetime puzzle experience predicted visuospatial cognition even after accounting for age, education, and other activities.

Stress, Cortisol, and Focus

The benefits extend beyond cognitive metrics.

Research published in Basic and Clinical Neuroscience (PMC8818112) measured physiological responses to puzzle-type activities. Participants showed significantly reduced salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase levels—objective biomarkers of decreased stress. Simultaneously, EEG measurements revealed increased attention markers, while neuropsychological testing confirmed improved sustained attention.

A follow-up study (PMC9985795) replicated these findings, with researchers concluding that puzzle activities can “strengthen and empower the perceptual-cognitive system and suppress the stress system.” The key distinction is that puzzles create what researchers term “logic stress”—the focused engagement of problem-solving—rather than “fear stress,” which elevates cortisol and impairs cognition.

The implications are significant. In an era of constant digital stimulation, activities that engage hands and mind together offer something increasingly rare: focused attention without anxiety.

Physical Puzzles vs. Digital Games

A 78-week randomized controlled trial from Duke University School of Medicine and Columbia University compared physical puzzles to computerized cognitive games in 107 participants with mild cognitive impairment. The results were striking.

Physical puzzles proved superior on cognitive measures at both 12 and 78 weeks. More remarkably, MRI scans revealed less brain shrinkage in the physical puzzle group. Dr. Murali Doraiswamy of Duke observed: “Hitting the trifecta of cognitive improvement, improvement in daily functioning and slowing brain shrinkage is like a holy grail in the field. To date, no drug in the Alzheimer’s field has hit all three endpoints.”

Harvard Health Publishing supports these findings, noting that mentally stimulating activities help the brain generate new cells and build “functional reserve” that provides protection against future cognitive decline. Activities combining manual dexterity with mental effort prove particularly beneficial.

Part Four: Where Craftsmanship and Learning Converge

The Ancient Art of Mechanical Puzzles

The tradition of building three-dimensional puzzles is itself ancient.

According to Wikipedia, the oldest known mechanical puzzle is the Ostomachion, a 14-piece dissection puzzle attributed to Archimedes in the 3rd century BC. The Chinese Rings puzzle appeared in European documentation by 1500, when mathematician Luca Pacioli recorded it in his manuscript De Viribus Quantitatis.

Japanese craftsmen developed the Kumiki tradition—meaning “to join wood together”—creating interlocking puzzles that taught construction principles used in earthquake-resistant architecture. The Yosegi-zaiku craftsmen of Hakone have created geometric wooden puzzles for approximately 200 years, using over 40 species of naturally colored woods. Their Himitsu-Bako (secret puzzle boxes) require solving sequential movements to open—some designs demand 72 separate steps.

What connects these traditions across cultures and centuries is a common insight: we understand complex systems more deeply when we build them ourselves.

Understanding Through Construction

This brings us back to the cello.

A luthier apprentice learning to build string instruments doesn’t begin by reading about acoustics. They begin by handling wood, shaping curves, fitting joints. The theoretical knowledge comes through physical engagement with materials.

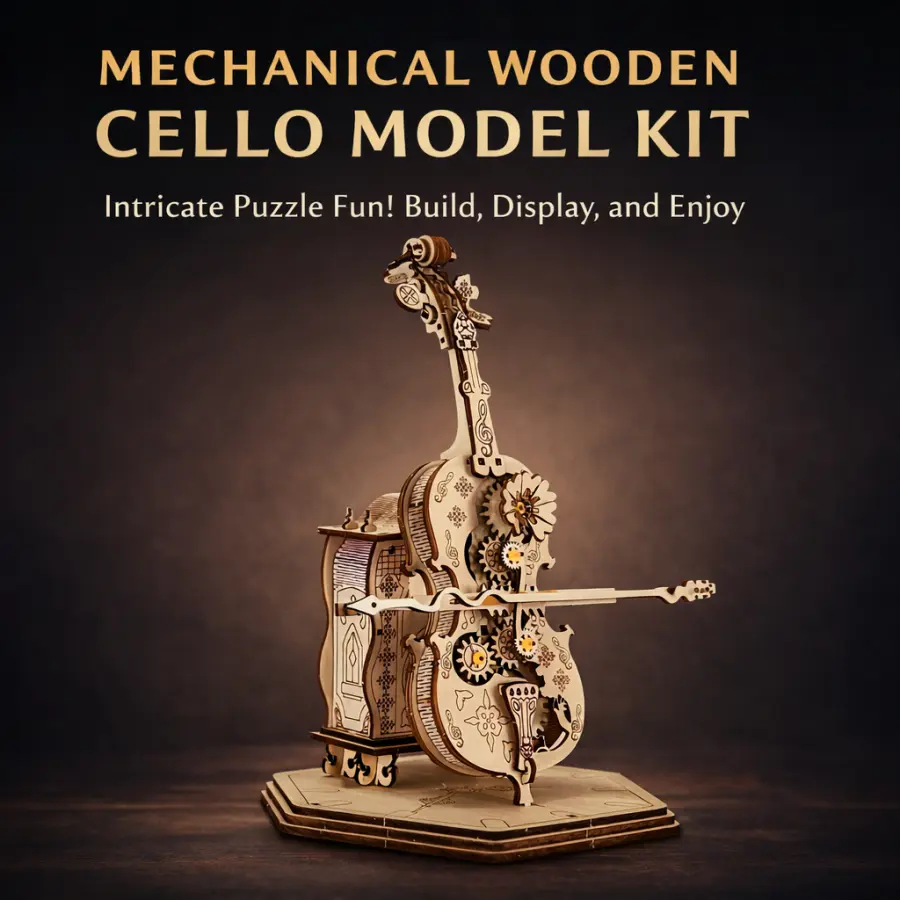

The same principle applies to understanding existing instruments. When you see a cello in a museum or concert hall, you observe its exterior. When you build a model, you engage with its structure—the arched top and back plates that create resonance, the C-bouts that define the instrument’s waist, the scroll that crowns the pegbox, the bridge that transmits string vibrations to the body.

Modern laser-cutting technology, evolved from Theodore Maiman’s first working laser at Hughes Research Laboratories in 1960, enables precision impossible with hand tools. Today’s CAD-controlled systems achieve tolerances under 0.1 millimeters, creating interlocking components that assemble without glue—echoing the mortise-and-tenon joinery that master luthiers have employed for centuries.

Part Five: Bringing History Home

The Value of Tangible Experience

We live in an age of abundant information and scarce experience.

Anyone with internet access can read about Andrea Amati’s workshops, view photographs of Stradivari cellos, listen to recordings of Bach’s suites. This accessibility is genuinely valuable—it democratizes knowledge that was once restricted to specialists and the wealthy.

But information is not the same as understanding. Watching a video about cello construction differs fundamentally from handling pieces that correspond to actual instrument anatomy. Reading about spatial reasoning differs from exercising it.

The scientific literature suggests this distinction matters for cognitive health. The Duke University study specifically compared physical activities to digital alternatives, finding the physical versions superior. The NIH research measured objective biomarkers—cortisol levels, brain activity patterns—that changed in response to hands-on engagement in ways that passive consumption did not produce.

A Connection Across Centuries

When you build a 3D wooden cello model, you participate in a tradition that connects Andrea Amati’s Cremona workshop to your own hands. The proportions you assemble reflect decisions made by Stradivari three centuries ago. The curves you fit together echo forms that produced Bach’s solo suites and Boccherini’s virtuosic compositions.

This is not the same as playing the instrument or hearing it performed. But it offers something different and complementary: a tangible understanding of how the cello achieves its remarkable expressive range.

The wooden puzzles available today translate centuries of craft tradition into accessible formats. Each piece corresponds to actual instrument anatomy. Assembly builds the spatial reasoning skills that researchers at Ulm University measured in their cognition studies. Completion provides a lasting reference object—a three-dimensional diagram that makes the cello’s engineering principles permanently visible.

Conclusion: Past, Present, and Future

The cello’s five-century journey from Catherine de’ Medici’s court to modern concert halls represents one of humanity’s great craft traditions. Each generation of luthiers built upon predecessors’ knowledge, optimizing proportions, improving materials, expanding expressive capabilities. The wire-wound strings developed in 1660s Bologna enabled Stradivari’s dimensional standardization in 1710, which enabled Bach’s revolutionary solo suites and the virtuosic repertoire that followed.

That accumulated knowledge exists today not only in museums and performance halls but in our understanding of how hands-on construction benefits cognitive function. The same spatial reasoning that allows a luthier to shape an instrument’s curves develops through puzzle assembly. The focused attention required for complex model building reduces stress biomarkers while strengthening working memory.

For music students, a cello model offers tangible understanding of instrument construction. For puzzle enthusiasts, it represents a thematic variation on spatial challenges with historical depth. For anyone seeking screen-free, mindful engagement, assembly provides hours of focused activity with a lasting result.

The tradition continues. Explore the complete puzzle collection to discover how traditional craftsmanship and modern precision combine to create meaningful building experiences.

Authority Citations

- Wikipedia – Cello Comprehensive historical documentation of the cello’s origins, development, and cultural significance. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cello

- Wikipedia – Cello Suites (Bach) Detailed information about Bach’s revolutionary solo compositions and their historical context. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cello_Suites_(Bach)

- Britannica – Cello Authoritative reference confirming the cello’s development during the 16th century and its evolution as a solo instrument. URL: https://www.britannica.com/art/cello

- Wikipedia – Mechanical Puzzle Historical background on mechanical puzzles dating to ancient Greece, establishing the cultural context of puzzle-building traditions. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mechanical_puzzle

- Wikipedia – Museo del Violino Information about the Cremona museum preserving Stradivari workshop materials and UNESCO heritage designation. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museo_del_Violino

- National Music Museum – University of South Dakota Documentation of “The King” Amati cello, the world’s oldest surviving cello. URL: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/national-music-museum-university-of-south-dakota

- Metropolitan Museum of Art – Musical Instruments Collection Information about the Met’s collection including Stradivari instruments. URL: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503975

- National Institutes of Health (PMC6174231) Fissler et al., “Jigsaw Puzzling Taps Multiple Cognitive Abilities and Is a Potential Protective Factor for Cognitive Aging” – Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2018. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6174231/

- National Institutes of Health (PMC8818112) Aliyari et al., “The Effect of Brain Teaser Games on the Attention of Players Based on Hormonal and Brain Signals Changes” – Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 2021. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8818112/

- National Institutes of Health (PMC9985795) “Evaluation of Stress and Cognition Indicators in a Puzzle Game: Neuropsychological, Biochemical and Electrophysiological Approaches” – Archives of Razi Institute, 2022. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9985795/

- Duke University School of Medicine Press release documenting 78-week randomized controlled trial comparing puzzles to digital cognitive games. URL: https://medschool.duke.edu/news/study-shows-crossword-puzzles-beat-computer-games-slowing-memory-loss

- Harvard Health Publishing “12 ways to keep your brain young” – guidance on mentally stimulating activities for cognitive health. URL: https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/12-ways-to-keep-your-brain-young