The Day the Sky Opened

On the afternoon of November 21, 1783, roughly 400,000 Parisians craned their necks toward the garden of the Château de la Muette. Among them stood Benjamin Franklin, the American diplomat whose experiments with lightning had made him a scientific celebrity. But this day, everyone’s eyes were fixed on something else: a massive fabric sphere, decorated in royal blue and gold, rising slowly into the autumn air.

Inside a wicker gallery suspended beneath the balloon stood two men—Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis François d’Arlandes. They were doing something no human being had ever done before: flying.

The balloon drifted over Paris for twenty-five minutes, traveling nine kilometers before landing near the Butte-aux-Cailles. The two pilots celebrated with champagne—a tradition balloonists still observe today. That night, every salon in Paris buzzed with the same question: If humans could conquer the sky, what came next?

The answer would unfold over the next two and a half centuries, through hydrogen balloons and rigid airships, transatlantic crossings and catastrophic disasters, until the dream of flight crystallized into something unexpected: a retro-futuristic aesthetic called steampunk that reimagines what Victorian technology might have become.

Part One: Paper Manufacturers and the Birth of Aviation

The brothers who launched humanity into the sky weren’t scientists or engineers. Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier ran their family’s paper manufacturing business in Annonay, a small town in southeastern France. But they were tinkerers, obsessed with a simple observation: heated air rises.

The story of their invention has become legend. One version has Joseph watching his wife’s chemise billowing above a fire and wondering if that force could lift heavier objects. Another describes the brothers heating paper bags over flames and watching them float to the ceiling. Whatever sparked the idea, by December 1782 they had built something never seen before: a large fabric envelope that, when filled with heated air, rose into the sky and traveled nearly two kilometers before crash-landing.

Their first public demonstration came on June 4, 1783, in Annonay’s market square. The balloon—eleven meters in diameter, constructed from sackcloth reinforced with paper—rose to an estimated altitude of 1,800 meters. The flight lasted ten minutes. Witnesses reported being struck dumb with wonder.

According to Wikipedia, the news spread rapidly. King Louis XVI demanded a demonstration at Versailles. The Montgolfiers obliged on September 19, 1783, launching a balloon carrying the first air passengers: a sheep named Montauciel (“Climb-to-the-sky”), a duck, and a rooster. The sheep was chosen because its physiology roughly resembled that of humans. The duck served as a control—if a creature built for high-altitude flight survived, the air itself wasn’t deadly. The rooster provided additional data, being a bird that normally stayed close to the ground.

All three animals landed safely after an eight-minute flight.

But the real breakthrough came two months later, when de Rozier and d’Arlandes made their historic manned flight. For the first time in recorded history, humans had left the ground and returned safely. King Louis XVI raised the Montgolfier family to nobility. And a new word entered the French language: balloonomania.

Part Two: The Race to Steer the Skies

Balloonomania was no exaggeration. Within weeks of the first manned flight, balloon imagery appeared on plates, cups, clocks, snuffboxes, jewelry, and even—according to contemporary accounts—the interior of a porcelain bidet. Women styled their hair à la montgolfier; men wore balloon-printed waistcoats. In England, poet William Wordsworth opened “Peter Bell” with the image of a balloon boat.

But balloons had a fundamental problem: they went wherever the wind pushed them. To be truly useful—for exploration, for commerce, for war—flight needed to become steerable.

The challenge consumed inventors for the next century. In 1852, French engineer Henri Giffard achieved the first powered airship flight, traveling 27 kilometers in a steam-driven vessel. But steam engines were heavy and underpowered. The breakthrough wouldn’t come until the late 1800s, with the development of the internal combustion engine.

Enter Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Zeppelin was 65 years old in 1900 when his first rigid airship, the LZ-1, lifted off from a floating hangar on Lake Constance in southern Germany. His interest in flight dated back decades. According to Wikipedia, he had first ascended in a balloon during the American Civil War, where he served as an observer with the Union Army and witnessed Thaddeus Lowe’s reconnaissance balloons in action.

The LZ-1 represented something fundamentally different from the soft-skinned balloons that came before. Its design featured a rigid metal framework—rings and longitudinal girders—covered in fabric and containing multiple internal gas cells. This structure allowed for much larger vessels that maintained their shape regardless of gas pressure fluctuations. The LZ-1 measured 128 meters long and was powered by two 15-horsepower Daimler engines.

The first flight lasted just twenty minutes and ended with a hard landing that damaged the craft. But Zeppelin had proven his concept. Over the next decade, he refined his designs, and by 1910, something extraordinary happened: the world’s first commercial airline began operating.

DELAG (Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-AG) carried more than 10,000 passengers on over 1,500 flights before World War I without a single passenger injury. The era of passenger air travel had begun—not with airplanes, but with airships.

Part Three: Giants of the Golden Age

The 1920s and 1930s became the golden age of the great airships. According to Britannica, the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin—launched in 1928—became the most successful airship ever built. Under the command of Hugo Eckener (whom Hitler later declared persona non grata for his anti-Nazi views), the Graf Zeppelin logged over 1.6 million kilometers. It completed 590 flights, including 144 ocean crossings and the first circumnavigation of the globe by aircraft.

Passengers aboard the Graf Zeppelin experienced something no airplane of the era could match: smooth, quiet travel at relatively low altitudes where scenery could be appreciated. The airship’s lounge featured windows that could be opened during flight—no pressurization was necessary at cruising altitudes of 200-300 meters. Travelers dined on white-tablecloth meals, slept in private cabins, and watched the Atlantic glide past below.

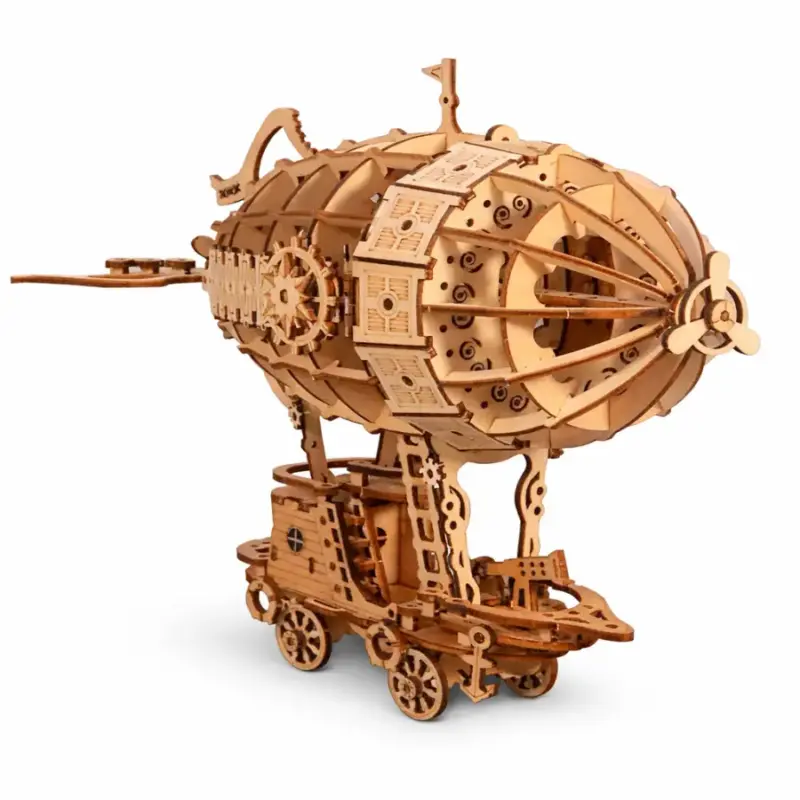

Steampunk Airship 3D Wooden Puzzle

What if Count Zeppelin had been born into a Jules Verne novel? This 160-piece steampunk airship imagines exactly that—a Victorian flying machine complete with spinning propeller, rolling wheels, and a captain’s cabin worthy of Robur the Conqueror. According to Wikipedia, steampunk reimagines 19th-century technology through a retro-futuristic lens, blending brass, gears, and steam-powered imagination. At just one hour of assembly time, you’ll have a conversation-starting desk piece that looks like it sailed straight out of 1886. Explore more wooden puzzles at Tea-Sip.

Even larger was the LZ 129 Hindenburg, launched in 1936. At 245 meters long, it remains the largest aircraft ever to fly. Its passenger accommodations—designed by the same firm that appointed Pullman cars and ocean liners—included a pressurized smoking room (the only safe place to light a cigarette aboard a hydrogen-filled vessel), a baby grand piano, and promenade decks with tilted windows offering views of the landscape below.

The Hindenburg completed 63 flights, including 36 Atlantic crossings. It could make the journey from Germany to the United States in roughly two and a half days—half the time required by the fastest ocean liners. The spire of the Empire State Building was even designed as a mooring mast for airships, though high winds made it impractical.

For a brief moment, it seemed the future of long-distance travel belonged to these majestic giants.

Then came May 6, 1937.

The Hindenburg was attempting to dock at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, when its tail caught fire. In 34 seconds, the massive airship was consumed by flames. Thirty-five of the 97 people aboard died, along with one member of the ground crew. Radio announcer Herbert Morrison’s anguished eyewitness account—”Oh, the humanity!”—was broadcast across America the following day.

The cause of the fire was never definitively determined. The official investigation concluded that a static spark had ignited hydrogen leaking from a damaged gas cell. The investigation also found that the Hindenburg‘s outer fabric covering was insufficiently grounded—a design flaw that was quietly corrected on subsequent airships but never publicly acknowledged.

Whatever the cause, the disaster ended the age of the great passenger airships. The Graf Zeppelin was retired one month later. A nearly completed sister ship, the LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II, made thirty flights for surveillance purposes but never carried paying passengers. Both surviving airships were scrapped in 1940.

The dream of elegant sky-cruisers, drifting serenely over continents, had lasted less than thirty years.

Part Four: Why We Still Look Up

A curious thing happened after the airship era ended. The great vessels vanished from the skies, but they never vanished from the imagination.

Throughout the twentieth century, airships appeared in science fiction, fantasy art, and alternative-history novels. Writers like Jules Verne had anticipated them—his 1886 novel Robur the Conqueror featured a fantastical flying machine called the Albatross, which scholars now describe as “proto-steampunk.” By the 1980s, authors like K.W. Jeter, Tim Powers, and James Blaylock were creating entire fictional worlds where Victorian technology had evolved along different paths, where steam power and elaborate mechanical devices dominated a society that never transitioned to electronics.

They called it steampunk.

According to Wikipedia, steampunk reimagines 19th-century technology through a retro-futuristic lens, featuring “anachronistic technologies or retro-futuristic inventions as people in the 19th century might have envisioned them.” The aesthetic draws heavily on Victorian industrial machinery—exposed gears, brass fittings, riveted panels—while rejecting the sleek minimalism of modern design.

Why does this aesthetic resonate so powerfully? Why do airships, in particular, continue to capture the imagination long after they ceased to be practical?

Modern cognitive science offers some interesting answers.

Research published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology (PMC6174231) found that activities requiring visuospatial reasoning—mentally rotating objects, understanding how pieces fit together, visualizing three-dimensional relationships—engage multiple cognitive abilities simultaneously. The researchers specifically studied jigsaw puzzles and found they recruited perception, mental rotation, processing speed, flexibility, working memory, and reasoning. Moreover, lifetime engagement in such activities was associated with better cognitive function in adults over 50.

A separate study (PMC9985795) examined how puzzle-solving affects the brain physiologically. The researchers found that puzzle activities decreased cortisol and alpha-amylase levels—both markers of stress. Unlike horror or violent games, puzzles produce what the researchers called “logic stress” rather than “fear stress.” This activates the prefrontal cortex—the brain region responsible for thinking, attention, and decision-making—without triggering the fight-or-flight response.

Perhaps this explains part of steampunk’s appeal. In an age of invisible technology—algorithms, radio waves, processes we can neither see nor understand—steampunk offers machinery that makes sense. Gears turn. Levers pivot. Steam condenses. The relationship between cause and effect remains visible, comprehensible, within human scale.

There’s also something deeper happening: a connection to human heritage. When we engage with historical machines—whether real or imagined—we’re participating in a conversation that spans generations. The Montgolfier brothers, Count Zeppelin, the engineers who built the Hindenburg—they all faced the same fundamental challenge: how do you make a heavier object float in air? Their solutions differ from ours, but the question remains timeless.

Part Five: Holding History in Your Hands

The story of human flight didn’t end with the Hindenburg. Airplanes became faster, safer, more economical. Rockets carried humans to the moon. Today we fly across oceans in pressurized cabins at 35,000 feet, watching movies and eating pretzels, barely aware of the miracle happening outside our windows.

But something was lost in that transition. The great airships moved slowly enough that passengers could watch the landscape unroll beneath them. Their exposed structures revealed how they worked. Their very existence seemed improbable—these enormous whale-shaped vessels drifting silently through clouds.

Steampunk culture has kept that sense of wonder alive. Its practitioners create clothing, jewelry, gadgets, and art that blend Victorian aesthetics with imaginative technology. Many enthusiasts describe themselves as “makers”—people who build things with their hands, who value craftsmanship and mechanical transparency over mass production.

This maker ethos connects to what cognitive researchers have discovered about hands-on activities. Building something—understanding how its parts relate, fitting pieces together, solving spatial problems—engages our brains in ways that passive consumption cannot. A study published in Developmental Psychology (PMC3289766) found that children who engaged in puzzle play showed better spatial transformation skills later in childhood. The benefits of working with our hands, it seems, begin early and persist throughout life.

For those drawn to the golden age of airships, wooden puzzles offer a way to engage with that history directly. When you assemble a model airship—fitting its framework together, attaching its gondola, mounting its propeller—you’re working through the same spatial relationships that occupied Zeppelin’s engineers. The scale is different, but the principles remain.

A steampunk airship model captures something of both the historical reality and the imaginative elaboration. Its design echoes the rigid airships of the early twentieth century—the elongated envelope, the suspended cabin, the rear propeller—while adding the decorative flourishes of steampunk aesthetics: visible gears, exposed framework, details suggesting impossible machinery beneath the surface.

Building such a model isn’t just recreation. It’s a form of engagement with a remarkable chapter in human history—a period when determined dreamers proved that humans could fly, when elegant sky-ships crossed oceans in style, and when the limits of possibility seemed infinitely expandable.

Conclusion: The Thread That Connects

Nearly two and a half centuries have passed since that November afternoon in 1783 when de Rozier and d’Arlandes drifted over Paris in their balloon. The technology has changed beyond recognition. But something essential remains constant: the human impulse to reach for the sky.

Every generation reimagines flight according to its own dreams. The Montgolfiers saw hot air as the key. Zeppelin envisioned rigid frameworks filled with hydrogen. Today’s makers and steampunk enthusiasts imagine alternative histories where brass and gears and steam power evolved along different paths.

What draws us to these visions isn’t nostalgia for a lost past. It’s something more fundamental—a recognition that the question of how to fly has never been truly answered, only temporarily settled. The great airships represented one possible future that didn’t quite happen. Steampunk imagines what might have been if it had.

When we engage with these visions—whether through reading, making, or building—we’re participating in a conversation that began in an Annonay marketplace in 1783 and continues today. The thread that connects Pilâtre de Rozier to Count Zeppelin to every child who has ever watched a balloon rise into the air is the same thread that connects us: wonder at what humans can accomplish when they refuse to accept that the sky is off-limits.

Explore more hands-on ways to connect with this history in our puzzle toys collection.

Authority Citations

- Wikipedia – Montgolfier Brothers Comprehensive overview of the Montgolfier brothers’ invention of the hot air balloon and the first manned flights in 1783. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montgolfier_brothers

- Wikipedia – History of Ballooning Detailed timeline of balloon development from Chinese sky lanterns through modern hot air balloons. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_ballooning

- Wikipedia – Zeppelin History of Ferdinand von Zeppelin and the development of rigid airships, including commercial operations and the Hindenburg disaster. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeppelin

- Britannica – Zeppelin Historical account of the first Zeppelin’s maiden flight and subsequent development of the airship industry. URL: https://www.britannica.com/technology/zeppelin

- Wikipedia – Hindenburg Disaster Detailed account of the May 6, 1937 disaster, including investigation findings and various theories about the cause. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster

- Wikipedia – LZ 129 Hindenburg Specifications and operational history of the largest passenger airship ever built. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LZ_129_Hindenburg

- Wikipedia – Hugo Eckener Biography of the master airship commander and his conflict with the Nazi regime. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugo_Eckener

- Wikipedia – Steampunk Definition and history of the steampunk subgenre, including its relationship to Victorian technology and aesthetics. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steampunk

- Wikipedia – Robur the Conqueror Overview of Jules Verne’s 1886 “proto-steampunk” novel featuring a fantastical flying machine. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robur_the_Conqueror

- PMC – Jigsaw Puzzles and Cognitive Function (PMC6174231) Research study on how jigsaw puzzling engages multiple visuospatial cognitive abilities and may protect against cognitive aging. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6174231/

- PMC – Puzzle Games, Stress, and Cognition (PMC9985795) Study examining how puzzle games reduce cortisol and alpha-amylase levels while improving cognitive function. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9985795/

- PMC – Brain Teaser Games and Attention (PMC8818112) Research on how puzzle games enhance prefrontal cortex function and improve sustained attention. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8818112/

- PMC – Early Puzzle Play and Spatial Skills (PMC3289766) Developmental study showing the relationship between children’s puzzle play and later spatial transformation abilities. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3289766/

- Wikipedia – Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier Biography of the first human to fly, including his later death attempting to cross the English Channel. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-François_Pilâtre_de_Rozier

- Wikipedia – Balloonomania Description of the cultural phenomenon that followed the first balloon flights in 1783. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balloonomania