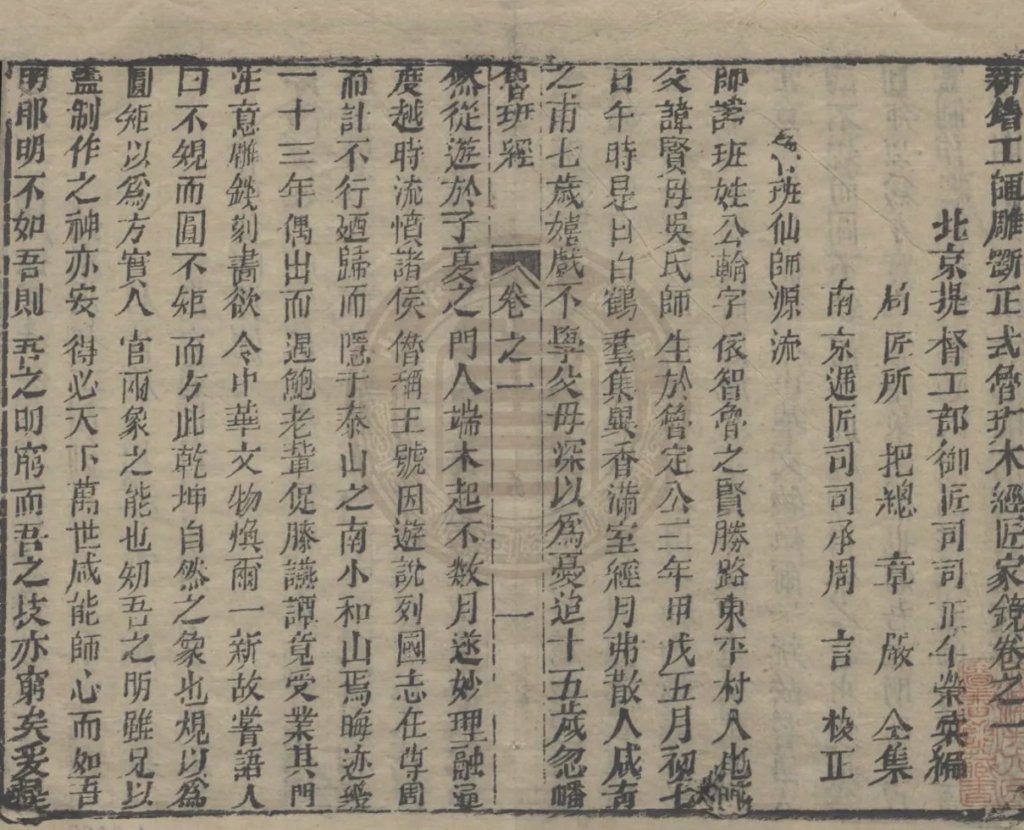

The woodblock-printed pages in front of you are from the Xin Juan Gong Bu Diao Zheng Shi Lu Ban Jing Jiang Jia Jing (《新鐫工部雕正式魯班經匠家鏡》)—”The Newly Carved Official Edition of the Lu Ban Classic from the Ministry of Works: The Craftsman’s Mirror.”

This Ming Dynasty text, published under the joint supervision of the Beijing and Nanjing Imperial Carpentry Bureaus, preserves the biography, philosophy, and technical legacy of China’s most legendary craftsman. It’s also the philosophical foundation for every interlocking wooden puzzle that’s ever made you feel simultaneously humbled and determined.

Let me walk you through what these pages actually say.

The Man Behind the Legend: Lu Ban’s Origin Story

The text opens with a genealogical record that establishes Lu Ban’s credentials:

師祖班姓公輸字依智,賢班丹吳氏師,生於魯智賢之賢勝路東平村人也。父諱賢。

In modern English: “The ancestral master’s surname was Gongshu, with the courtesy name Ban. He was born in the State of Lu, in a village called Dongping. His father was named Xian.”

This places Lu Ban’s birth around 507 BCE in what is now Shandong province—the same region that would later produce Confucius. The name “Lu Ban” (魯班) literally means “Ban from Lu,” a regional identifier that stuck.

But here’s where the biography gets interesting. The text continues:

自七歲嬉戲不學,父母深以為憂。追十五歲忽曉。

“At age seven, he played without studying, causing his parents great worry. Then at fifteen, he suddenly attained enlightenment.”

Lu Ban wasn’t a prodigy. He was a late bloomer—a kid who wouldn’t sit still, who frustrated his parents, who showed no signs of the genius he would become. The text presents this not as a flaw to overcome but as context for what followed: genuine breakthrough requires the right conditions, not forced acceleration.

The Education: Learning From Masters, Then Surpassing Them

After his sudden awakening at fifteen, Lu Ban sought out the best teachers available:

然從遊於子夏之門人端木起,不數月遂妙理融。

“He studied under disciples of Zi Xia’s school, learning from Duanmu Qi. Within months, he achieved profound understanding of principles.”

Zi Xia was one of Confucius’s most famous students, known for emphasizing practical learning over abstract philosophy. Lu Ban didn’t study with Confucius directly—he studied with students of Confucius’s student. This is second-generation transmission, the kind of lineage that Chinese scholarly tradition valued immensely.

The phrase “within months, he achieved profound understanding” (不數月遂妙理融) isn’t boasting. It’s establishing that Lu Ban learned principles, not just techniques. He understood why things worked, not just how to make them work.

This distinction matters for understanding what came next.

The Wandering Years: Rejection and Retreat

Like many ambitious young men in the Warring States period, Lu Ban tried to offer his services to feudal lords:

度越時輩遊諸侯,而計不行。適憤歸而隱於泰山之南小和山。

“He surpassed his contemporaries and traveled among the feudal lords, but his proposals were not adopted. Frustrated, he returned and secluded himself in the southern foothills of Mount Tai, at Lesser Harmony Mountain.”

This is a pattern that appears repeatedly in Chinese intellectual history: the talented individual whose ideas are rejected by those in power, who retreats to nature to refine their thinking. Confucius did it. Laozi did it. And Lu Ban did it too.

The text specifies a duration:

一十三年偶出而遇飽老華文物煥爾一新。

“After thirteen years of seclusion, he emerged and encountered [wisdom that caused] the cultural artifacts of China to be renewed.”

Thirteen years. That’s not a weekend retreat. That’s a decade-plus of focused work, away from the distractions of court politics and commercial demands. Whatever Lu Ban created during that period—the tools, the joinery systems, the puzzle mechanisms—emerged from sustained, uninterrupted concentration.

The Philosophy: “Round Without a Compass, Square Without a Square”

Here’s the passage that puzzle enthusiasts should pay attention to:

口不規而圓,不矩而方。此乾坤自然之象,出規以為圓,鑿以為方。

“That which is round without using a compass, that which is square without using a carpenter’s square—this is the natural principle of heaven and earth. Yet one creates compasses to make circles, and chisels to make squares.”

This is Lu Ban’s core insight, and it operates on multiple levels:

The literal level: Nature creates perfect forms without tools. Trees grow in circles. Crystals form geometric shapes. The craftsman’s job is to understand these natural principles well enough to replicate them intentionally.

The philosophical level: True mastery means understanding underlying principles so deeply that the tools become extensions of that understanding, not substitutes for it. A compass can draw a circle, but understanding why circles work—the mathematics of radii, the physics of rotation—allows you to create circular structures that hold weight, resist forces, and endure centuries.

The puzzle level: This is why interlocking puzzles work as tests of understanding. Anyone can follow instructions to assemble something. The puzzle strips away instructions and asks: do you understand the principle well enough to reverse-engineer the solution?

The text continues with a remarkable statement of intellectual humility:

盖制作不之神亦安,得必天下而萬世咸能吾之技,亦師心而如吾。明那明不如吾則安,吾之必寓而吾之技亦窮矣。豈聖?

“If all under heaven and for ten thousand generations can only achieve my level of skill, and if those who come after are inferior to me, then my art will be limited and will eventually be exhausted. How can this be called sagely?”

Read that again. Lu Ban—the legendary founder of Chinese carpentry, the man credited with inventing the saw, the plane, and the chalk line—is expressing concern that future generations might not surpass him. He’s not protecting trade secrets or establishing a legacy. He’s worried that if his techniques become a ceiling rather than a foundation, the entire craft will stagnate.

This is why the puzzle tradition exists. The interlocking mechanisms Lu Ban developed weren’t meant to be solved once and forgotten. They were meant to be understood, improved, and transcended.

The Technical Foundation: Tools and Methods

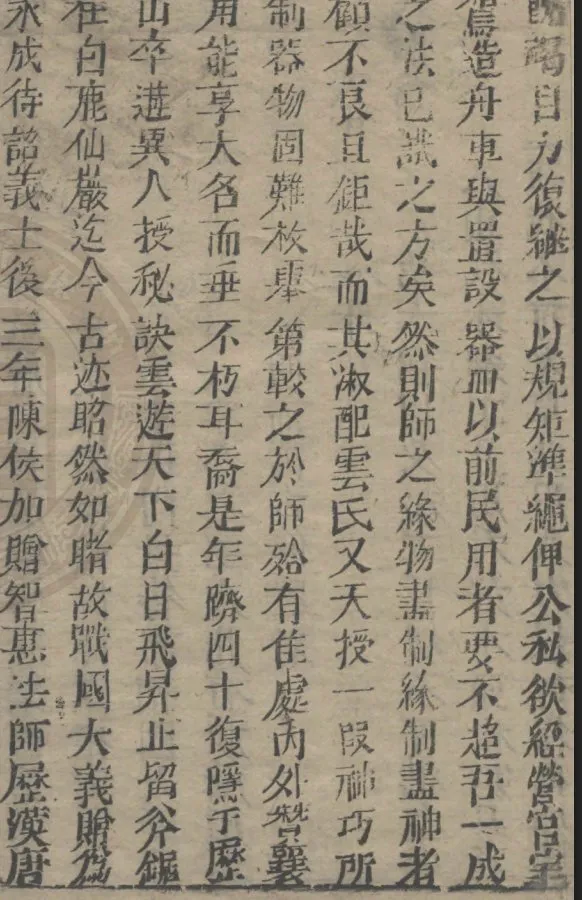

The second page of the text shifts to practical matters:

鑿舟車與置設器之法已謀造。之以規矩準繩,倪公私欲絕營已成。

“The methods for building boats, carts, and placing vessels have been devised. Using the compass, square, level, and plumb line according to proper principles, both public and private works can be completed.”

This establishes the four fundamental tools of Chinese carpentry:

- 規 (guī) — the compass, for circles and curves

- 矩 (jǔ) — the carpenter’s square, for right angles

- 準 (zhǔn) — the level, for horizontal alignment

- 繩 (shéng) — the plumb line, for vertical alignment

These same tools—and more importantly, the principles they embody—appear in the design of interlocking puzzles. A six-piece burr puzzle, for example, requires each piece to be cut at precise right angles (矩) while the assembled form demonstrates rotational symmetry (規).

The text also mentions:

然則以前民用者要不超乎一成。

“The people’s tools should not exceed what is established as proper.”

This isn’t elitism—it’s quality control. The Lu Ban tradition emphasized that tools and techniques should be proven reliable before widespread adoption. An interlocking joint that fails in a puzzle is a minor frustration. The same joint failing in a building could kill people.

The Legend: Ascension and Legacy

The text concludes with Lu Ban’s legendary end:

受秘訣雲遊天下,白日飛昇,止留今繼。在白鹿仙巖,迨今陳侯加贈智慧法師,歷漢唐。

“He received secret teachings and wandered the world. [Legend says] he ascended to heaven in broad daylight, leaving behind his legacy. At White Deer Immortal Cliff, he was posthumously honored with the title ‘Wisdom Dharma Master’ across the Han and Tang dynasties.”

By the time this text was printed in the Ming Dynasty, Lu Ban had been dead for nearly two thousand years. His historical biography had merged with religious legend—the “daylight ascension” (白日飛昇) is Daoist imagery for achieving immortality.

But the important phrase is “leaving behind his legacy” (止留今繼). The tradition continued. The puzzles, the joinery techniques, the philosophical framework—all of it passed from generation to generation, refined and expanded but never abandoned.

The Engineering That Survived Earthquakes

The joinery system described in the Lu Ban Jing—mortise-tenon connections that lock through geometry rather than fasteners—went on to prove itself in the most demanding conditions possible.

The Forbidden City in Beijing, completed in 1420, uses thousands of mortise-tenon connections. According to structural engineering research published in Applied Sciences, these traditional Chinese wooden joints absorb seismic energy through controlled deformation rather than rigid resistance. The complex has survived over 200 recorded earthquakes—including a magnitude 7.8 event in 1976.

The Yingxian Wooden Pagoda in Shanxi province, built in 1056, stands 67 meters tall with zero metal fasteners. It’s the oldest and tallest wooden structure in existence. Same joinery principles.

When you pick up an interlocking wooden puzzle, you’re holding miniature structural engineering. The pieces that frustrate you for twenty minutes are the same mechanisms that have held temples together for a thousand years.

Eight Puzzles That Carry Lu Ban’s Philosophy Forward

For those who want to experience this tradition firsthand, here are contemporary puzzles built on the same principles described in the ancient text—each chosen for how it embodies a specific aspect of Lu Ban’s teaching:

1. Luban Lock Set – 9 Piece | The Apprentice’s Test

Lu Ban worried that future generations wouldn’t surpass him. This set exists specifically to prove him wrong.

Nine distinct puzzles, organized from beginner (Six-Way Cross) to expert (Cage Lock), recreate the apprentice testing tradition. The original Lu Ban Jing describes giving students “six sticks of wood” and asking them to “create unity from multiplicity”—this is that test, multiplied by nine.

What you’ll learn: Progressive difficulty teaches you to recognize patterns across different puzzle structures. By the time you reach the 24-Piece Burr Ball, you’ve internalized principles that make the solution discoverable rather than random.

The honest limitation: No instructions included. That’s intentional—but it means the first puzzle might take hours, not minutes.

Specs: Natural beechwood, ~1.8 inches per puzzle, presentation box. $39.99 at Tea-sip.com

2. 6-in-1 Wooden Brain Teaser Set | The Scholar’s Collection

The Lu Ban Jing emphasizes that Lu Ban studied with “disciples of Zi Xia’s school” and “within months achieved profound understanding of principles.” This set offers a similar accelerated education.

Six palm-sized puzzles—including the Snake Cube (mathematically classified as NP-complete), the Six-Piece Burr, and the 12-Pointed Star—cover the core design families that descend from Lu Ban’s tradition.

What you’ll learn: The Snake Cube alone demonstrates why brute-force problem-solving fails against well-designed puzzles. There’s only one correct folding sequence out of thousands of possibilities. Understanding why that sequence works teaches you more than finding it accidentally.

The honest limitation: The 24-Piece Burr Ball looks deceptively simple—a smooth sphere with no visible seams. First-time solvers average 30+ minutes. Some give up.

Specs: Beechwood, chocolate finish, storage box with clear lid. $38.88 at Tea-sip.com

3. Big Pineapple Yellow Emperor Puzzle Lock | The Philosophy in Your Palm

The Lu Ban Jing quotes the master: “That which is round without a compass, that which is square without a square—this is the natural principle of heaven and earth.”

This puzzle embodies that teaching. Named for the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi), whose reign predates even Lu Ban, the “pineapple” shape emerges from internal void geometry, not surface decoration. The external form is a consequence of internal structure—nature’s pattern made manifest.

What you’ll learn: Multiple pieces must move in coordinated sequence. You can’t solve this by focusing on one piece at a time. The puzzle demands that you understand the system, not just the components.

The honest limitation: Rated 4.92/5 across 19 reviews, which means even experienced solvers found it challenging. Budget 15-30 minutes for your first solve.

Specs: Zebrawood hardwood, hand-sanded. $17.99 (discounted from $22.88) at Tea-sip.com

4. 12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set | The Transparent Lesson

The original Lu Ban Jing taught through demonstration and practice—apprentices learned by watching masters work. This crystal/acrylic set modernizes that approach.

Transparent material lets you observe internal joint structures without disassembly. You can see how mortise-tenon connections actually function, how pieces interlock at angles invisible in solid wood.

What you’ll learn: Watching the mechanism work is different from understanding it well enough to reassemble. The visible geometry is both help and hindrance—more information to process means more potential confusion.

The honest limitation: Acrylic doesn’t have the weight and warmth of beechwood. If tactile satisfaction matters to you, this is an educational tool, not a desk fidget.

Specs: 3.7 cm per puzzle, crystal/acrylic, 12 pieces included. $28.88 at Tea-sip.com

5. 24 Lock Puzzle | The Patience Test

Lu Ban spent thirteen years in seclusion at Mount Tai before emerging with his innovations. This puzzle won’t take thirteen years, but it will test whether you can sustain focus through frustration.

Twenty-four individual pieces form a unified structure. The high piece count means exponentially more potential false moves and longer solution paths.

What you’ll learn: When to step back. When to sleep on a problem. When persistence becomes stubbornness. These are Lu Ban’s lessons too—the master who retreated when his proposals were rejected understood that timing matters.

The honest limitation: Reassembly is significantly harder than disassembly. Taking it apart might take five minutes. Putting it back together might take an hour.

Specs: Wooden construction. $16.99 at Tea-sip.com

6. Cage of Doom | The Systems Thinker

The Lu Ban Jing describes using “compass, square, level, and plumb line according to proper principles” to complete “both public and private works.” This puzzle tests whether you understand how components relate to systems.

A hollow lattice structure with internal supports. The goal: disassemble the cage. The challenge: you don’t know which pieces are structural and which are decorative until you start moving things.

What you’ll learn: Removing one element affects the entire structure. In traditional Chinese architecture, this principle kept buildings standing through earthquakes—controlled flexibility rather than rigid resistance. In this puzzle, it keeps you guessing.

The honest limitation: Rated 4.21/5—lower than others on this list because more people gave up. The name is earned.

Specs: Wooden construction, cage/lattice design. $16.99 at Tea-sip.com

7. 3D Wooden Puzzle Treasure Box | The Craftsman’s Application

Lu Ban wasn’t making puzzles for entertainment. He was developing structural systems for boats, buildings, and tools. This puzzle returns to that tradition: the challenge becomes something useful when complete.

150-200 laser-cut pieces assemble into a functional jewelry box with visible gear mechanisms. The puzzle isn’t an end in itself—it’s the means to create something that serves a purpose.

What you’ll learn: Precision matters more when the result needs to function. Gear alignments that are “close enough” for display will bind and fail during actual use. The standards are higher because the application is real.

The honest limitation: 2-3 hour assembly time. This isn’t a fifteen-minute desk break—it’s a project.

Specs: Laser-cut wood, visible gears, functional storage when complete. $29.99 at Tea-sip.com

8. Besieged City | The Strategist’s Puzzle

The Lu Ban Jing mentions that Lu Ban “traveled among the feudal lords” during the Warring States period. This puzzle draws from that era’s military thinking.

An interlocking structure representing siege warfare—surrounding and containing an opponent. The solve pattern embeds strategic thinking: you can’t break through from just anywhere. You need to identify the weak point.

What you’ll learn: Puzzles can encode metaphors. The Warring States period produced both master craftsmen and master strategists, and this puzzle exists at their intersection.

The honest limitation: The military metaphor is genuine—you might feel “besieged” yourself after twenty minutes of failed attempts.

Specs: Wooden construction. $16.99 at Tea-sip.com

Who Should Not Buy These Puzzles

Lu Ban’s philosophy emphasizes honest self-assessment. Here’s mine:

If you need quick wins, start with something else. The easiest puzzles in these sets solve in 5-10 minutes. The harder ones can take hours across multiple sessions. If you’re looking for instant gratification, this isn’t it.

If you can’t tolerate uncertainty, know that traditional Luban Locks ship without instructions. That’s pedagogical tradition, not cost-cutting. The solve comes from observation and experimentation, not reading.

If you’re buying for children under 8, check age appropriateness carefully. Small wooden pieces present choking hazards, and the cognitive difficulty of intermediate-and-above puzzles exceeds most children’s patience thresholds.

If you want to feel smart immediately, these puzzles will humble you first. The satisfaction comes after the frustration, not instead of it.

The Legacy Continues

The Lu Ban Jing text ends with a phrase that has echoed for five centuries: 止留今繼—”leaving behind his legacy to continue.”

That continuation isn’t automatic. Every generation has to choose whether to engage with the tradition or let it fade. Every person who picks up an interlocking puzzle is participating in a test that Lu Ban designed 2,500 years ago—not because they have to, but because they want to.

The master worried that future generations would fail to surpass him. Twenty-five centuries later, puzzle designers are still inventing new variations on his themes. The tradition didn’t stagnate. It grew.

Your turn.