On the evening of June 21, 1893, a nervous crowd gathered at Chicago’s Midway Plaisance. Above them, an impossible structure groaned to life: a 264-foot steel wheel carrying 2,160 passengers skyward in 36 gondolas. Engineer George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. stood below, watching his audacious answer to the Eiffel Tower complete its first revolution. In the same era, half a world away in the Jura Mountains of Switzerland, craftsmen were perfecting another rotating marvel—cylinders studded with pins that plucked steel combs to produce melodies without electricity, without musicians, without anything but precise engineering.

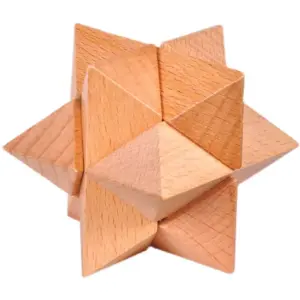

Both inventions shared something profound: the transformation of circular motion into wonder. Today, these two mechanical traditions converge in a single object that sits on your desk—a wooden Ferris wheel music box puzzle that you build with your own hands.

Act One: Origins — When Rotation Became Music

Long before George Ferris sketched his wheel on a napkin, humans had been obsessed with making objects spin and sing. The earliest known mechanical musical instrument emerged in 9th-century Baghdad, where the Banū Mūsā brothers built a hydropowered organ that played interchangeable cylinders automatically. By the 13th century, Flemish bell ringers had invented pin-studded cylinders to automate their tower carillons, freeing themselves from endless repetition.

The leap from church tower to parlor table took centuries. In 1796, a Geneva clockmaker named Antoine Favre-Salomon replaced the bells with something smaller and cheaper: a steel comb with tuned teeth. Each tooth vibrated at a specific pitch when plucked. Arrange enough teeth in ascending size, add a cylinder with precisely placed pins, and you had a portable orchestra.

Switzerland’s Sainte-Croix region became the epicenter of music box production. The Passaic County Historical Society notes that by the 1880s, Swiss workshops were producing music boxes with up to 25 tuned teeth, each screwed separately into position on the comb. Labor was cheap, materials abundant, and demand insatiable. These boxes weren’t toys—they were the only way ordinary people could hear complex music at home, decades before phonographs existed.

The mechanisms grew increasingly sophisticated. Some boxes featured interchangeable cylinders, allowing owners to swap melodies like changing records. Others added bells, drums, and even tiny organs. A single comb might contain over 100 teeth, capable of reproducing operatic arias with surprising fidelity. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History houses several Swiss orchestra boxes from this era, including one from 1885 featuring 63 comb teeth, nine bells, an eight-beater drum, and a 36-note organ.

But what made these machines truly remarkable wasn’t their complexity—it was their accessibility. Unlike pianos or violins, music boxes required no skill to operate. Wind the spring, release the mechanism, and music appeared as if by magic. For the first time in history, anyone could summon a symphony.

Act Two: Evolution — From Town Square Carillons to Pocket-Sized Wonder

The journey from cathedral bell tower to tabletop music box mirrors another transformation happening simultaneously: the miniaturization of rotating observation devices. Before Ferris, so-called “pleasure wheels” had existed for centuries as crude wooden contraptions at village fairs. Riders sat in baskets attached to a central hub, lifted briefly skyward by human or animal power.

The 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle changed everything. The Eiffel Tower proved that steel could reach impossible heights while remaining elegant. American fair organizers, planning Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, felt compelled to respond. According to the National Endowment for the Humanities, architect Daniel Burnham specifically sought “an innovative and striking attraction that would rival the Eiffel Tower.”

George Ferris answered the call. His design scaled up the pleasure wheel concept using the same steel construction techniques that had built the Eiffel Tower. The result was a 250-foot diameter wheel supported by two 140-foot steel towers, powered by two 1,000-horsepower steam engines. The wheel’s 45-foot axle weighed nearly 90,000 pounds and remains one of the largest single-piece steel forgings ever cast.

The parallels to music box engineering are striking. Both technologies depended on precision manufacturing that had become possible only in the Industrial Age. Both transformed simple circular motion—a cylinder rotating, a wheel turning—into experiences that felt transcendent. And both faced the same fundamental challenge: making something large enough to impress while keeping it balanced enough to function smoothly.

The original Ferris wheel operated flawlessly throughout the exposition, carrying nearly 1.5 million passengers without incident. The University of Illinois notes that “a trip consisted of one revolution, during which six stops were made for loading, followed by one nine-minute, nonstop rotation.” Riders paid 50 cents—equivalent to roughly $17 today—for twenty minutes of gentle rotation and unparalleled views of Chicago.

After the fair, the wheel was dismantled, relocated twice, and finally destroyed with 200 pounds of dynamite in 1906. But the concept endured. Every observation wheel in the world traces its lineage to Ferris’s Chicago original, just as every music box descends from those Swiss comb mechanisms.

Act Three: Cultural Peak — The Golden Age of Mechanical Wonder

The late 19th century represented a unique moment in technological history. Electricity existed but hadn’t yet conquered every corner of daily life. Steam power dominated industry, but homes remained largely mechanical. Into this gap rushed an explosion of clockwork marvels: singing birds in gilded cages, automaton musicians, cylinder music boxes playing twelve tunes, and—towering above them all—rotating observation wheels.

The American Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association documents that by 1900, more people owned music boxes than any other automatic musical instrument. The mechanisms appeared everywhere: jewelry boxes, clocks, holiday novelties, children’s toys. Production expanded from Switzerland to Germany, England, Italy, and eventually America.

Music boxes of this era weren’t just functional—they were beautiful. Craftsmen favored rosewood and walnut cases because mahogany and oak “deadened sound.” They inlaid zinc, brass, and mother-of-pearl. They polished mechanisms until gears gleamed. The finest boxes commanded prices equivalent to several months’ wages, yet still sold briskly.

The same aesthetic philosophy drove fair architecture. The 1893 Chicago exposition’s “White City” featured neoclassical buildings with gleaming plaster facades, formal gardens, and electric lighting that made the grounds shimmer at night. The Ferris wheel, with its 36 wood-paneled gondolas and ornate iron framework, fit perfectly into this culture of mechanical elegance.

PBS’s Antiques Roadshow has appraised numerous Swiss cylinder music boxes from this period. A typical orchestra box from 1880-1890 might include a 43-tooth comb, eight interchangeable tunes, and a percussion section with bells, drums, and castanets. Appraisers note that condition matters enormously—a working mechanism with intact comb teeth commands premiums.

What ended this golden age? Thomas Edison’s phonograph arrived in 1877 but remained a curiosity for decades. The real death blow came from disc music boxes, which emerged in Germany in 1885. Discs were cheaper to produce than cylinders and easier to swap. But even discs couldn’t compete with recorded sound once gramophones improved. By 1920, the music box industry had largely collapsed.

The Ferris wheel, surprisingly, survived. Its descendants still spin at state fairs and amusement parks worldwide. The London Eye, the High Roller in Las Vegas, the Ain Dubai in the UAE—all trace their ancestry to that Chicago wheel. The mechanical music box, by contrast, became a curiosity, a collector’s item, a nostalgic artifact.

Until something unexpected happened.

Act Four: The Science of Building — What Happens When Hands Meet Mechanics

Modern science has begun explaining what Victorian craftsmen understood intuitively: working with mechanical objects does something valuable to human brains. Research published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience found that jigsaw puzzling “strongly engages multiple cognitive abilities,” including perception, constructional praxis, mental rotation, processing speed, flexibility, working memory, reasoning, and episodic memory.

The study, conducted at Ulm University with 100 adults aged 50 and older, measured performance across eight distinct visuospatial cognitive domains. Participants who solved puzzles for 30 days showed improved puzzle-solving skills, though the researchers noted that long-term puzzle experience showed stronger correlations with cognitive performance than short-term practice.

Another study in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry examined nearly 20,000 adults aged 50-93 and found that “the frequency of word puzzle use is directly related to cognitive function.” Those who engaged in puzzles regularly performed better on tests of focused attention, sustained attention, information processing, executive function, working memory, and episodic memory.

But puzzles aren’t just about cognition. Research published in PMC on stress and puzzle games found that puzzle-style activities “enhance the function of the prefrontal cortex, which plays an important role in cognitive abilities, such as thinking, decision making, concentration, and problem-solving.” The same research noted that puzzle games produced “logic stress”—a beneficial form of cognitive challenge without the harmful cortisol spikes associated with time pressure or fear.

Fine motor coordination—the precise hand movements required to assemble small parts—engages additional brain regions. The NIH’s StatPearls notes that “fine motor ability is usually synonymous with…the ability of an individual to make precise, voluntary, and coordinated movements with their hands.” Dr. Penfield’s famous homunculus demonstrates that hands occupy a disproportionately large region of the motor and sensory cortex relative to their physical size.

Perhaps most intriguingly, research on “flow states” suggests that activities matching skill level to challenge produce optimal psychological experiences. A study in PMC found that “more cognitively demanding activities elicited higher levels of flow for those with higher fluid ability.” Assembling a mechanical model—with its clear goals, immediate feedback, and graduated difficulty—creates ideal conditions for flow.

This scientific foundation explains something that Tea-Sip customers often report: building mechanical puzzles feels different from passive entertainment. It’s absorbing without being stressful, challenging without being frustrating, satisfying in ways that scrolling through screens never achieves.

Act Five: Modern Experience — Bringing Victorian Wonder to Your Desk

The screen fatigue of our era has created an unexpected hunger for tangible objects. We spend hours swiping glass rectangles, accumulating nothing physical, building nothing permanent. The appeal of mechanical models lies precisely in their physicality: real wood, real gears, real motion that you assembled with your own hands.

Contemporary wooden puzzle kits draw directly from both the music box and Ferris wheel traditions. Laser-cut plywood replaces hand-sawn lumber, but the fundamental engineering remains identical: rotating cylinders, tuned steel combs, gear trains translating motion between components. You build something that actually works, not a static display.

One couple we heard from started building these puzzles as a way to spend evenings together without screens. Four months later, they’ve finished eight kits and have a shelf dedicated to their collection. “We do one per month now,” they told us. “It’s become our thing.” That tracks with what researchers found about flow states—when challenge matches skill, time disappears. Apparently so do Netflix queues.

A science teacher in Austin uses her completed Ferris wheel in physics class to demonstrate gear ratios. Her 15-year-old daughter helped build it over a weekend, and watching the dual music movements layer their harmonics gave both of them something to geek out about. “You can actually see how the gear train translates motion,” she said. “Way better than a diagram.”

Not everyone nails it on the first try. One builder rushed through the gear alignment, skipping the wax application, and ended up with a wheel that stuttered instead of spinning smoothly. Her second build went perfectly after she followed every step—including the part where the instructions say “grease all gears.” The lesson here: the sandpaper and wax aren’t optional accessories. They’re problem-solvers.

The Ferris Wheel That Plays Music

One expression of this tradition is the Wooden Ferris Wheel Music Box Kit, which combines both engineering lineages in a single desktop object. The 235-piece assembly takes 2-3 hours—or closer to 4 if you’re the type who savors the process rather than racing to the finish.

What makes this particular model distinctive is the inclusion of two music movements rather than the single mechanism found in most music boxes. A retired aerospace engineer who’s built model aircraft for forty years called the dual-movement design “genuinely clever acoustic engineering.” When both mechanisms play simultaneously, the harmonics layer in ways that a single movement simply can’t produce.

The wheel rotates while the music plays, driven by the same hand crank that powers the melody. There’s also a hidden drawer in the base—small but functional, good for a spare key or folded note. Multiple builders have mentioned discovering the drawer mid-assembly and treating it like finding a secret room in a house.

Parents building with kids report mixed results depending on age. A dad who tackled the kit with his 6-year-old did most of the work himself while she helped with the simpler pieces. His honest assessment: “A child would need to be closer to 10 or 11 to do this on their own.” Meanwhile, a 12-year-old assembled one completely solo as a gift, then immediately asked for another kit. The 14+ age recommendation reflects fine motor precision requirements, but determined younger builders have proven it’s not a hard ceiling.

No glue is required; pieces interlock through tab-and-slot construction, with screws securing the music movements. The finished model stands 14 inches tall—substantial enough for display, compact enough for a desk corner. For those building collections of mechanical models, the Ferris wheel complements other music box designs like carousels, pianos, and cello models. The Wooden Puzzles collection includes similar builds at various difficulty levels.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does assembly actually take? The product specifies 2-3 hours. Community experience suggests this is accurate for focused builders following instructions carefully. Those who rush or skip steps may encounter gear alignment issues requiring rework.

Do I need glue or special tools? No glue required. The kit includes sandpaper for smoothing tight joints and a screwdriver for mounting music movements. Pieces connect through tab-and-slot interlocking.

Will the wheel actually rotate? Yes. The hand crank powers a gear train that rotates the wheel while simultaneously driving two music movements. All motion is synchronized.

What song does it play? Melody varies by production batch. Many music movements use well-known classical or popular tunes, but specific songs aren’t guaranteed unless explicitly stated.

Is this appropriate for children? Recommended for ages 14+. The fine motor precision required and small parts involved make it challenging for younger builders. Teens and adults typically find it most satisfying.

How loud is the music? Classic music-box volume—charming and clear, but not room-filling. Think desk companion rather than speaker replacement.

What if pieces don’t fit? Use the included sandpaper to smooth snug joints. Alignment matters for smooth motion; small adjustments usually resolve friction issues.

Does the hidden drawer actually work? Yes. It’s small but functional—enough space for a spare key, coins, or folded notes.

Conclusion

That June evening in 1893, when Ferris’s wheel completed its first revolution, spectators understood they were witnessing something unprecedented. A structure that should have collapsed had instead proven graceful, stable, beautiful. The average worker who earned $1.50 per day couldn’t afford the 50-cent ticket, but those who did ride never forgot it.

The music boxes of that era produced similar wonder on a smaller scale. Winding the key, releasing the spring, hearing impossible melodies emerge from brass and steel—it felt like capturing magic in a wooden case.

Today, we can build both marvels ourselves. The wheel that once required 4,600 tons of steel now fits in 235 wooden pieces. The mechanisms that Swiss craftsmen spent lifetimes perfecting arrive pre-assembled, ready to install. What remains unchanged is the satisfaction of watching gears mesh, hearing pins pluck comb teeth, seeing rotation become music.

Perhaps that’s what both Ferris and those Geneva clockmakers understood: some experiences can’t be streamed, downloaded, or swiped. They must be built—slowly, carefully, with hands that remember the work long after the mechanism starts turning.

Explore more mechanical builds in the Puzzle Toys collection.

Authority Citations

| Source | Domain | Section | Key Fact | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Endowment for the Humanities | .gov | Ferris history | Original wheel was 264 feet high, served as blueprint for modern wheels | https://edsitement.neh.gov/media-resources/flight-1893-ferris-wheel |

| NEH Teacher’s Guide | .gov | 1893 World’s Fair | Burnham sought attraction to rival Eiffel Tower; Ferris was inspired by 50-foot roundabouts | https://edsitement.neh.gov/teachers-guides/1893-worlds-fair-and-first-ferris-wheel |

| Library of Congress | .gov | Ferris Wheel photos | 1.5 million paid 50 cents each; term “midway” coined at this fair | https://blogs.loc.gov/picturethis/2016/07/a-trip-around-the-ferris-wheel/ |

| National Park Service | .gov | Chicago inventions | Ferris wheel debuted at 1893 fair to rival Paris Exposition | https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/inventions-from-the-world-s-columbian-exposition.htm |

| University of Illinois | .edu | Ferris Wheel history | Trip consisted of one revolution with six stops, then nine-minute nonstop rotation | https://omeka-s.library.illinois.edu/s/idhh/page/worlds-columbian-exposition-the-white-city-midway-plaisance-and-ferris-wheel |

| University of Iowa Engineering Library | .edu | Ferris biography | Ferris born Valentine’s Day 1859; graduated Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute | https://blog.lib.uiowa.edu/eng/let-the-spinning-wheel-spin/ |

| PubMed Central | .gov | Cognitive research | Jigsaw puzzling engages eight visuospatial cognitive abilities | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6174231/ |

| PubMed | .gov | Puzzle frequency study | Word puzzle use directly related to cognitive function in adults 50+ | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30443984/ |

| PubMed Central | .gov | Flow states | Cognitively demanding activities elicit higher flow in those with higher fluid ability | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3199019/ |

| PubMed Central | .gov | Puzzle games stress | Puzzle games enhance prefrontal cortex function | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9985795/ |

| NIH StatPearls | .gov | Fine motor skills | Hands occupy disproportionate motor/sensory cortex region | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563266/ |

| Wikipedia | .org | Music box history | First mechanical musical instrument: 9th century Baghdad | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_box |

| Smithsonian | .edu | Music box collection | Swiss orchestra box from 1885 with 63 teeth, bells, drums, organ | https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_605787 |

| Passaic County Historical Society | .org | Music box industry | Swiss workshops by 1880s produced 15-25 tooth combs | https://lambertcastle.org/the-age-of-the-music-box/ |

| AMICA (Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors) | .org | Music box evolution | Carillon design adapted and miniaturized to become music box | https://www.amica.org/files/publications/History_of_the_Music_Box.pdf |