A carpenter walks onto a building site and the first thing he checks is not the wood, not the soil, not the tools. He checks the sky. He consults a calendar. He calculates which celestial positions align with today’s date. Only then does he pick up a saw.

This sounds like superstition. It is not. Or at least, it is not only that. Behind the cosmological language lies one of the most rigorous systems of construction planning ever committed to paper — a system that forced builders to slow down, verify conditions, and treat every decision as consequential before a single joint was cut.

The records that describe this system survived because someone broke the unwritten rule of the craft and wrote everything down anyway.

The Red Bird and the Calendar of Doors

Among the oldest construction planning systems recorded in the Chinese building tradition is one called “Red-Beaked Vermilion Bird” — named after the southern constellation grouping in Chinese astronomy. It governed something specific: when and how to modify doors and gates.

The system cross-referenced the sexagenary cycle — a sixty-unit calendar combining ten Heavenly Stems and twelve Earthly Branches — with particular architectural actions. Renovating a front gate in the third month required checking one set of alignments. Modifying a rear door in the ninth month demanded another. Each month-action pair carried a designation: auspicious, dangerous, or prohibited.

Read charitably, this was a quality control system disguised as metaphysics. Every construction decision required consultation, cross-referencing, and verification before execution. In a world without building inspectors or engineering review boards, the cosmic calendar functioned as a mandatory pause — a forced breath between intention and action.

Anyone who has tried to rush through a traditional wooden puzzle and jammed a piece that would have slid easily with more patience has experienced the same principle in miniature. The old builders encoded it into their professional calendar.

The Dimension Ruler That Reads Like a Moral Code

The most practically influential tool in the old building records is not a saw or a plane. It is a ruler — but not the kind that simply measures distance.

Traditional builders used a specialized measuring device divided into eight named segments, each approximately one cun (about 3.3 centimeters) wide. The segments carried names that translate roughly as: wealth, illness, separation, righteousness, officialdom, disaster, harm, and prosperity. The total length of any door opening, window frame, or gate would fall on one of these segments, and builders adjusted their dimensions to land on favorable divisions.

The practical effect was this: builders could not simply make a door whatever size was structurally convenient. They worked within a constraint matrix that forced creative problem-solving and extreme measurement precision. Calculations were recorded down to fen — units of approximately three millimeters. Maintaining that accuracy across an entire structure required not just good tools but trained hands and disciplined attention.

This constraint-based approach to design produced buildings of remarkable proportional coherence. Nothing was arbitrary. Every element related to every other through a web of proportional relationships.

Modern designers call this “integrated design” and treat it as an advanced methodology. The writers who recorded these practices describe a different article on how puzzle design mirrors mechanical engineering principles — constraints that look limiting actually generate better outcomes.

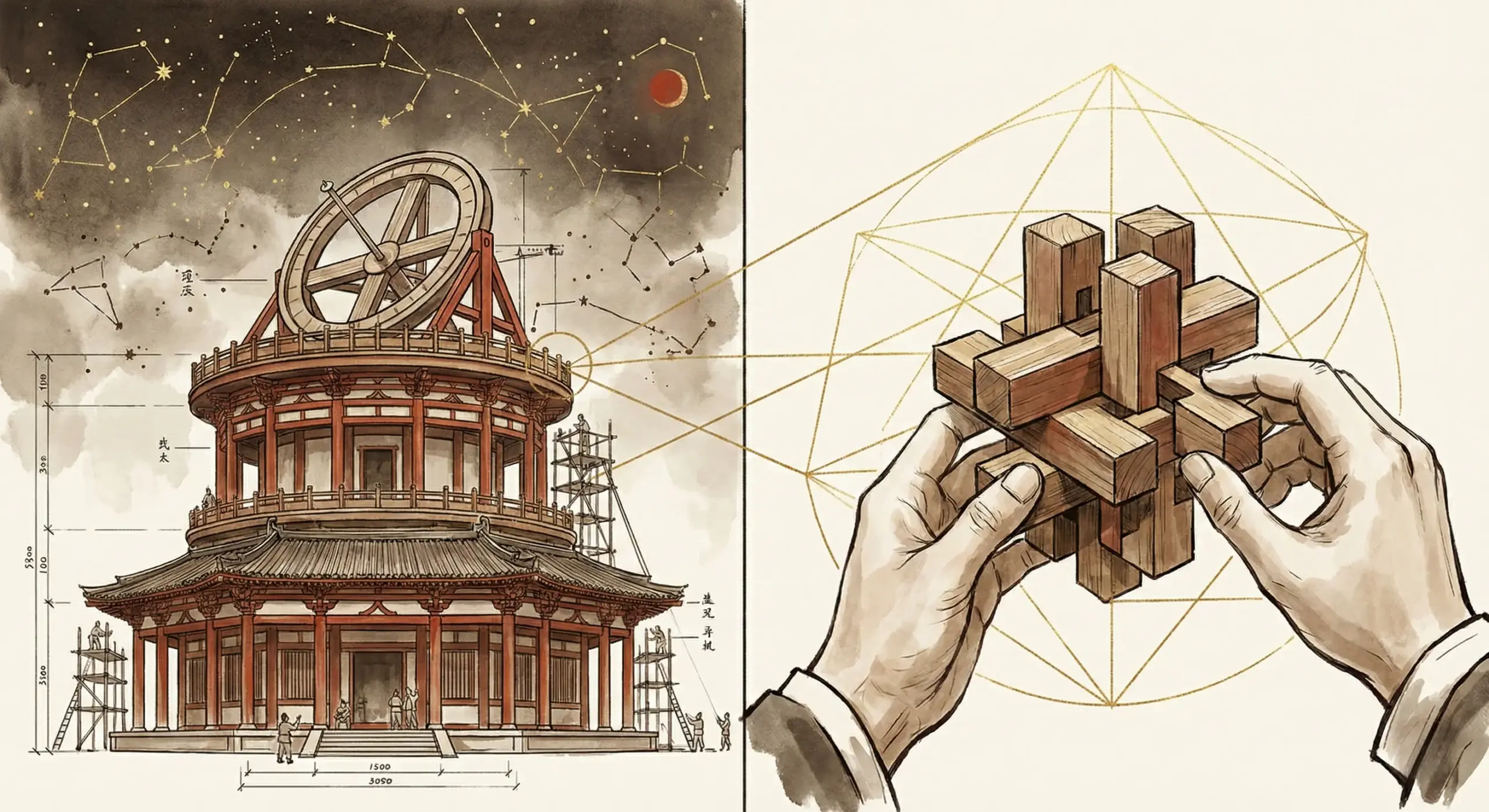

Building a Machine to Watch the Sky

The most technically ambitious passage in these records describes the construction of a Sitian Tai — a celestial observation platform. This was not a simple raised viewing deck. It was a precision instrument built from wood and stone, designed to track stellar and planetary positions with enough accuracy to maintain a functional calendar system for an entire empire.

The specifications are extraordinarily detailed. The platform required an octagonal base with columns at each vertex, multiple observation tiers, and a central rotating disc — the tianpan, or “heaven disc” — that could be turned to align with different stellar configurations. The disc had to be perfectly round, perfectly level, and smooth enough to rotate without wobbling under the weight of instruments mounted on its surface.

Consider what this demanded. Eight equal sides meant geometric precision at architectural scale. A rotating central platform meant understanding friction, balance, and weight distribution well enough to create a functional bearing from wood and bronze. Multiple tiers had to align vertically with sightline accuracy sufficient for astronomical observation in all cardinal and intermediate directions.

The text specifies that the builder was expected to understand astronomy — the positions of twenty-eight lunar mansions were to be marked on the platform’s eight faces. The builder was writing the sky into the bones of the structure. Each measurement served two purposes simultaneously: structural integrity and observational accuracy.

Luban Lock Set — 9 Piece

The same spatial logic that governed observatory construction survives in a form you can hold in two hands. This set of nine interlocking wooden puzzles recreates the designs attributed to Lu Ban himself — the legendary carpenter whose name became synonymous with Chinese building craft. Each puzzle uses mortise-and-tenon joinery with no nails, no glue, just geometry holding wood against wood.

The difficulty range spans from the approachable Six-Way Cross to the genuinely tricky Luban Ball. What makes the set useful rather than merely decorative is the variety — nine different spatial problems, each requiring a distinct approach to disassembly and reassembly.

- 9 interlocking wooden puzzles in one set

- Mortise-tenon joinery, no adhesives or fasteners

- Difficulty ranges from beginner to advanced

- Price: $39.99

View the Luban Lock Set 9 Piece →

Skip this if you want a single focused challenge rather than a survey course. Nine puzzles means breadth over depth — none of them individually will occupy you for more than an afternoon.

Water Reads the Land Before the Builder Does

Not everything in the old records concerns celestial timing. A substantial section addresses something more immediately practical: how to evaluate a building site by reading water flow, terrain, and natural drainage.

One passage describes tracing water paths around a potential site, noting where streams converge, where moisture pools, and where drainage moves naturally downhill. Another explains assessing rock formations and orienting a structure to work with the land’s natural water movement rather than against it.

The language uses feng shui terminology — literally “wind-water” — but the practical content reads like a modern site survey. Check drainage. Identify flood risk. Orient for moisture management. Avoid placing foundations where water collects. A particularly vivid line warns against building where water strikes sand and stone, breaking against rock faces — which is a flood-and-erosion risk assessment wrapped in vivid imagery.

Even psychological aspects of site selection appear. A building where visitors approach unseen creates unease. Internal pathways that confuse waste time and breed friction. A hall oriented so natural light falls on work areas without blinding occupants improves daily life. These observations read less like mysticism and more like the accumulated wisdom of people who paid close attention to how environments shape behavior — not unlike the careful observation explored in how collectors and solvers approach wooden puzzles differently.

Chinese Koi Puzzle Lock

Traditional Chinese locks embody the same principles as the building tradition: hidden internal logic, precise metalwork, and a mechanism that reveals itself only to patient hands. This koi-fish-shaped lock functions as both a working padlock and a puzzle — the unlocking sequence is not obvious, and brute force accomplishes nothing.

The fish form is not decorative whimsy. Koi symbolize persistence and upward progress in Chinese culture, and the lock’s mechanism echoes that theme: you must discover the correct sequence through trial and careful observation.

- Functional padlock with hidden puzzle mechanism

- Cast metal in traditional koi fish form

- Requires sequential discovery to unlock

View the Chinese Koi Puzzle Lock →

Skip this if you want a pure manipulation puzzle. This is as much a display piece as a brain teaser — and that is precisely the point for some buyers, but not for everyone.

Poems as Construction Code

Scattered throughout the records are short verses — mnemonics encoding construction principles. One describes parallel rooflines channeling water toward each other, warning that the space between will become a perpetual moisture trap. Another warns against placing a gate facing a direct approach path — metaphorically called a “hidden arrow” — which exposes the entrance to wind, noise, and psychological discomfort.

These were not literature. They were technology: a compression format for complex spatial reasoning, designed to survive in human memory through rhythm and imagery. A builder who memorized the verses carried a portable reference library of design failures to avoid.

The practice of encoding knowledge into memorable patterns hasn’t disappeared. It has just changed storage media. Puzzle solvers develop their own internal libraries of strategies, built through experience and refined by failure. The builders’ verse tradition and a modern solver’s muscle memory serve the same function — compress what you know into patterns you can access quickly when it matters. The shift from poetry to practice is something explored in a piece on what happens when puzzles become a daily practice.

The Hierarchy of Rooms

The old records make sharp distinctions between structure types. A family dwelling, a temple, and a government hall each required different proportions, materials, and ornamentation. The distinctions reveal how traditional Chinese society encoded social meaning into physical space itself.

A main hall (zheng ting) required columns of a specific minimum diameter, a roofline of a particular pitch, and door openings scaled to the building’s total footprint. Temples received more elaborate detailing — carved brackets, ornamental ridges, and specific interior arrangements for ritual purposes. Humble dwellings used simpler proportions but followed the same underlying geometric logic.

One passage describes a paifang — a decorative archway — with carved lions at the base, multiple tiers of upturned eaves, and a central tablet for inscriptions. The specifications cover everything from overall height to individual roof tile curvature. It reads less like architecture and more like a recipe: a precise sequence that, followed correctly, produces consistent results.

The confidence is what strikes a modern reader. No discussion of artistic inspiration. No invocations of genius. Just method, practiced until it becomes instinct. Mastery through repetition rather than revelation — a philosophy that also runs through the Yin-Yang logic game, where solutions emerge from systematic pattern testing rather than flashes of insight.

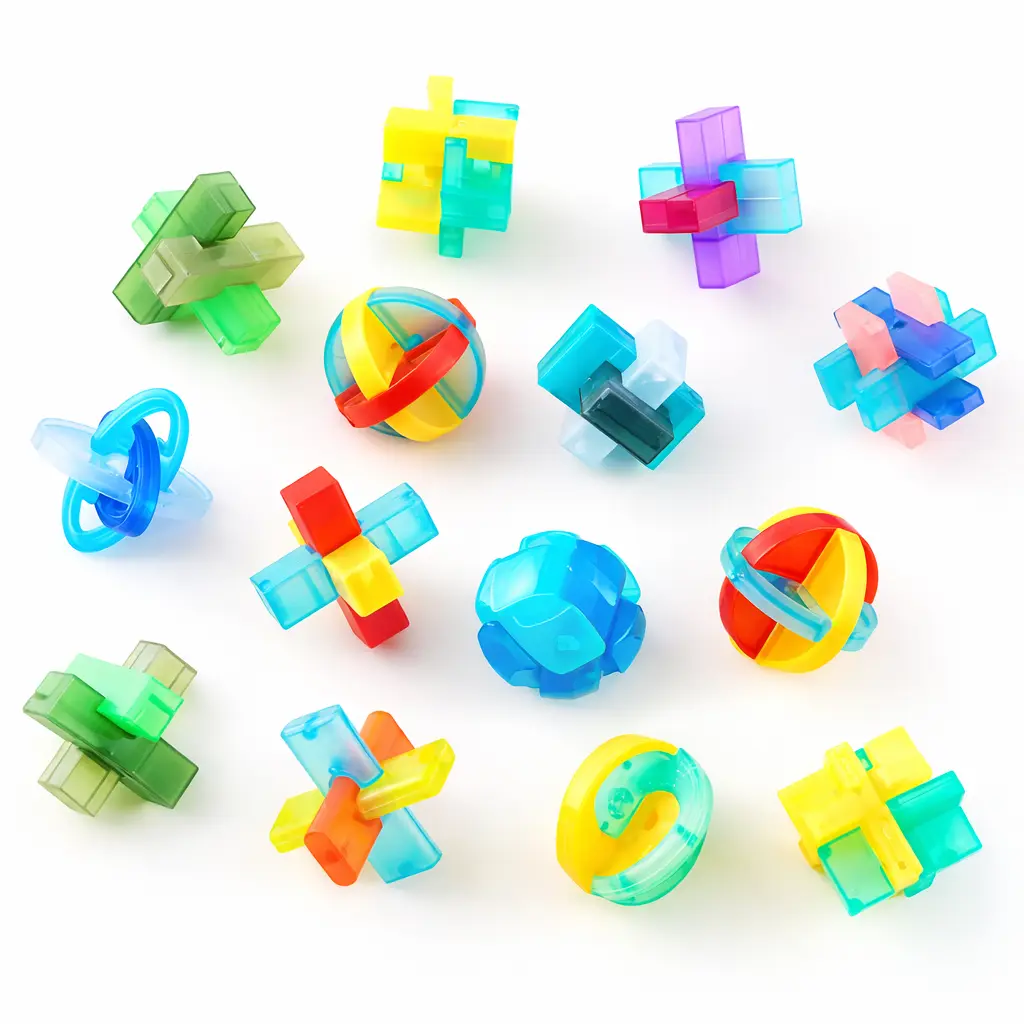

12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set

If the wooden Luban locks descend from the building tradition’s emphasis on concealed joinery, this crystal set adds a twist: you can see the mechanism clearly, and it still defeats you.

Each of the twelve mini locks (3.7–5.5 cm) is made from transparent acrylic, exposing every notch and groove. Visibility does not equal solvability. The internal geometry is complex enough that seeing the structure gives you less advantage than you’d expect — your hands still need to discover the correct disassembly sequence.

- 12 miniature transparent Luban locks

- Each measures 3.7–5.5 cm

- Visible internal mechanism

- Price: $28.88

View the 12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set →

Skip this if you prefer the tactile warmth of wood. Crystal acrylic feels different in the hand — lighter, cooler, less organic. For some that is a dealbreaker. For others, seeing the geometry is half the fascination.

Precision Down to Three Millimeters

The records contain page after page of specific dimensions — column heights, beam widths, door frame thicknesses, lattice spacing. Reading them feels like watching someone count threads in silk. Every measurement is recorded in traditional units with brief explanations of why that dimension matters.

A door frame might be specified at a particular width because that width falls on a favorable segment of the measuring ruler. A column height might be calculated to create a specific proportional relationship with room width. Every dimension served both structural function and aesthetic coherence simultaneously.

This dual-purpose measurement system is what gives traditional Chinese buildings their remarkable sense of unity. Nothing was arbitrary. Every element related to every other through proportional relationships that a trained builder could verify with ruler and eye.

The same kind of proportional integrity distinguishes well-made puzzles from mediocre ones. A 6-in-1 wooden brain teaser set at $38.88 demonstrates this — each puzzle in the set holds together through the same geometry-as-fastener principle the old builders used, and tolerances of a fraction of a millimeter determine whether pieces slide smoothly or bind uselessly.

What the Old Builders Knew About Attention

There is a deeper lesson running beneath the specific construction techniques, one that transcends its historical context: the quality of what you build depends on the quality of attention you bring to building it.

This is not a motivational platitude. It is an engineering observation. The observatory failed if the builder rushed the octagonal base. The door brought problems if the builder ignored dimensional constraints. The temple felt proportionally wrong — acoustically, visually, in the quality of light — if measurements were treated as approximate.

Attention, in this tradition, was a technical skill. Not an attitude. Not a personality trait. A skill — developed through practice, measured by results, and visible in the finished work.

The building tradition treated every apprenticeship as a long education in noticing. The first lessons were never about tools or materials. They were about learning to see what was already in front of you — the grain direction of a beam, the slight flex in a joint under load, the way morning light fell across a half-finished frame and revealed misalignments invisible at noon.

That education in perception is something the Yin-Yang algorithm of ancient systems thinking explores from a philosophical angle: the traditional Chinese insight that understanding comes from sustained attention to complementary forces, not from forcing a single perspective.

Three Brothers Lock Puzzle

Three interlocking metal pieces that look like they should come apart in seconds. They do not. The Three Brothers Lock requires you to find a specific rotational alignment before any piece will move — a small-scale version of the observatory builder’s challenge of aligning rotating elements with precision.

The metal construction gives it a satisfying weight, and the casting tolerances are tight enough that the puzzle rewards careful manipulation over brute force.

- Three interlocking cast metal pieces

- Rotational alignment required for disassembly

- Rated 4.80 out of 5

- Price: $11.99

View the Three Brothers Lock Puzzle →

Containers, Hidden and Open

The records describe buildings as containers for human life — shaped and proportioned to serve the activities within. Temples contain ritual. Halls contain governance. Homes contain family. Even the decorative elements served containment functions: carved screen walls inside compound gates controlled sightlines and airflow simultaneously, while ornamental lattice windows filtered light into patterns that marked the passage of hours across interior floors.

The same logic scales down elegantly. A 3D Wooden Puzzle Treasure Box is a miniature building whose purpose is to conceal and protect, using nothing but joinery and hidden mechanisms. Its sequential unlocking process mirrors the step-by-step construction sequences described in the building records — each element enabling the next, skipping steps impossible. You build your way into the box the same way a builder raised a structure: one verified step at a time.

For those drawn to the lock tradition specifically, the Chinese Old Style Fú Lock carries the “fortune” character and functions as both working hardware and puzzle object. The old builders would have recognized it instantly — a mechanism where form serves function serves meaning, all in one piece of metal.

And for a more portable encounter with constraint-based thinking, the Antique Bronze Metal Keyring Puzzle puts the challenge literally on your keychain — a small cast metal disentanglement that rides in your pocket and demands three-millimeter accuracy from your fingers every time you pick it up.

Who Should Walk Past All of This

Not everyone should spend time on objects descended from the old building tradition, and pretending otherwise would be dishonest.

If you want instant results, these puzzles will feel like punishment. The building records describe apprenticeships lasting years before a builder was trusted with independent work. The objects that descend from that tradition carry the same expectation: mastery comes from sustained engagement, not quick wins.

If ambiguity frustrates rather than motivates you, the hidden-mechanism puzzles — locks, boxes, sequential discoveries — will generate more anger than satisfaction. Their whole design philosophy depends on concealing the path forward.

If you dislike working with your hands, if tactile manipulation feels tedious rather than engaging, the entire category will miss its mark. These are objects that communicate through touch. Reading about them teaches you approximately nothing useful about solving them.

If you want a definitive, one-time challenge, a set like the Luban Lock Set may disappoint after the initial solve. The replay value depends on whether you find reassembly meditative or merely repetitive.

And if you primarily want display pieces — objects that look interesting on a shelf but never leave it — you will get more value from art than from puzzles. These objects exist to be handled. A puzzle lock collection gathering dust fails at its fundamental purpose.

The Rooms You Already Occupy

You probably cannot redesign your living space from scratch. But you can apply the old builders’ principle: every object in a space should be there for a reason, and that reason should serve the person using it.

A desk that holds only what the current task requires. A shelf arranged so frequently-used objects sit at hand height. A single well-chosen object that rewards close attention — something with a hidden mechanism, a satisfying weight, a geometry that reveals itself only through handling.

The building records describe structures where every dimension served both function and meaning. You can create the same coherence at desktop scale. The mechanical puzzle collection guide sorts options by the kind of thinking they develop rather than by price or novelty, which is a reasonable starting point for intentional selection.

The old builders would tell you to check the calendar first and make sure the timing is right. Between us — any time you choose to sit down and pay actual attention to something real is auspicious enough.

If you want to test your spatial reasoning in a quick, low-stakes way before committing to a physical puzzle, the memory match game offers a two-minute version of the same pattern-recognition challenge that the old builders trained for over years. It will not make you a carpenter. But it will tell you whether this kind of thinking appeals to you at all.