The third time the small hardwood dowel slipped past my thumb and rattled onto the floor, I didn’t swear. I didn’t reach for a hammer. I set the half-assembled mess down, walked to the kitchen, and made a very slow cup of coffee. I’ve tested over 200 mechanical puzzles in the last decade, and if there is one thing I’ve learned, it’s that wooden puzzles don’t care about your IQ. They care about your blood pressure.

Most people approach these objects with the wrong kind of energy. They treat it like a math problem or a locked door. But a wooden puzzle is more like a conversation with a very quiet, very stubborn person. If you shout (or pull too hard), they shut down. The secret to how to solve wooden puzzle designs isn’t found in a manual; it’s found in the fingertips. It’s about learning to feel the “give” in the grain and the microscopic gaps where a piece is begging to slide.

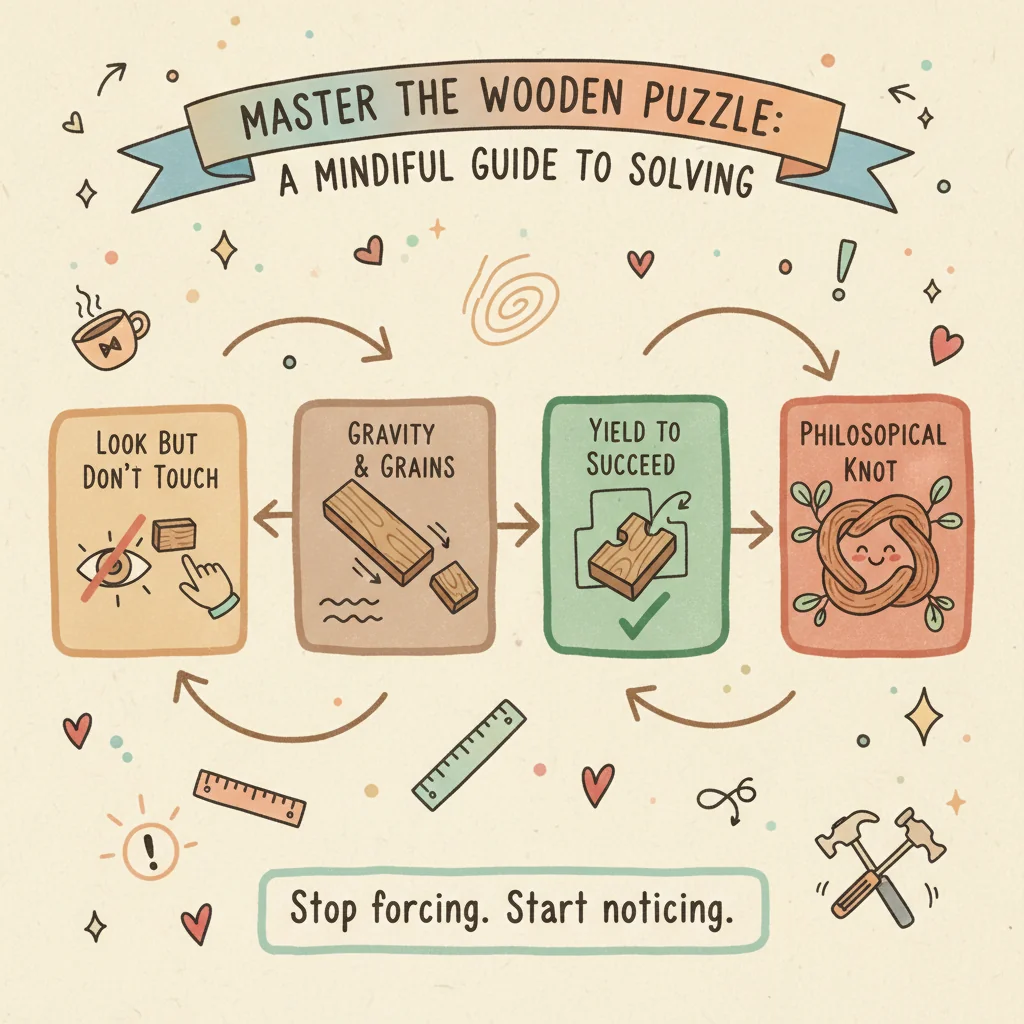

My thesis is simple: The best wooden puzzles are designed to punish impatience and reward observation. If you are forcing a piece, you aren’t solving it—you’re breaking it. True mastery comes from the “Wu Wei” approach—effortless action where you stop trying to make the pieces fit and start noticing where they want to go.

The “Look But Don’t Touch” Phase of the Solve

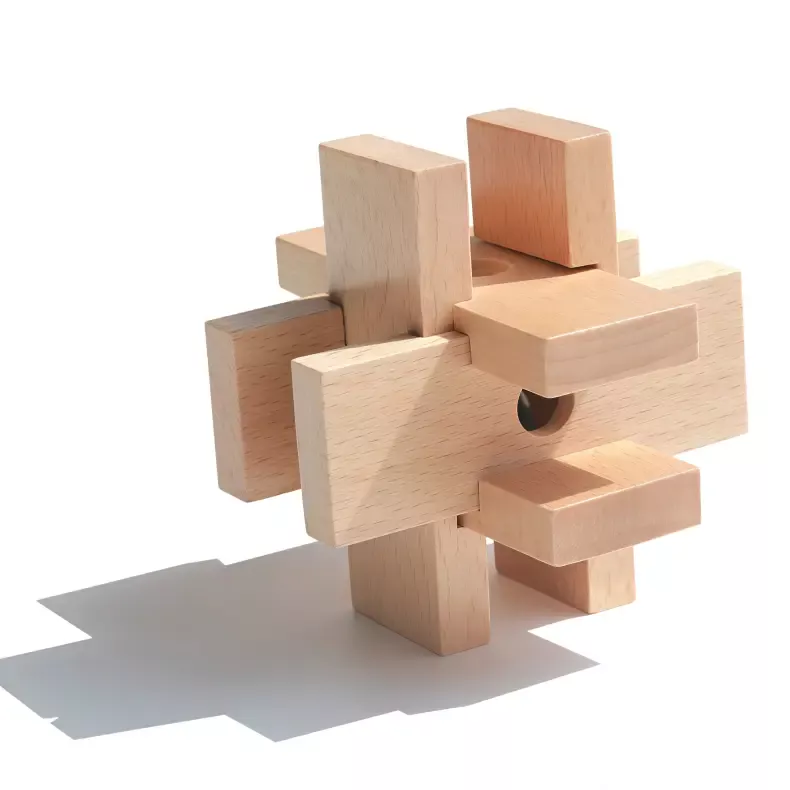

When you first unbox a challenge like the Six-Piece Burr ($17.99), your instinct is to start pulling. Don’t.

Six-Piece Burr — $17.99

I spent twenty minutes just staring at my first six-piece burr before I even moved a finger. You need to identify the “key” piece—the one that has no notches or the one that seems to have a fraction of a millimeter more wiggle room than the others. In the Six-Piece Burr, everything is held together by friction and geometric locking. If you can’t find the first move, you’re likely looking at the wrong axis.

A Burr puzzle is essentially a three-dimensional grid. Most beginners try to pull pieces “out” when they should be sliding them “across.” I’ve seen smart engineers get humbled by this because they assume the wood is rigid. Wood is an organic material; it breathes, it expands with humidity, and it has a “nap.” Learning to read the grain can actually tell you which direction a piece was intended to slide. If you find yourself struggling with the physical movement, navigating the nuances of secret compartments in other wooden designs can often provide the foundational logic you need to understand how wood interacts with wood.

Gravity is Your Secret Consultant

We often forget that puzzles exist in a world with gravity. If a piece won’t move, try turning the puzzle upside down. Some designs, like the Looking Back ($16.99), rely on internal pins or shifting weights that only disengage when the orientation is exactly right.

Looking Back — $16.99

The Looking Back is a fascinating example of how poetry and physics collide. Inspired by Xin Qiji’s legends, it uses 12 sticks of varying lengths. The “twist” mentioned in the description isn’t just a metaphor—it’s a literal mechanical requirement. I’ve handed this to friends who tried to pull it apart like a wishbone, only to realize that a gentle rotation was all that was needed. It’s a romantic design, but it’s also a lesson in humility. The noble is rooted in the humble, as the Taoists say, and the solution to this puzzle is usually rooted in the smallest, most overlooked movement.

If you’re the type who gets frustrated by gravity-based locks, you might find translucent geometry challenges a bit more predictable, as you can often see the internal pins through the plastic. But with wood, you have to listen. I often hold a puzzle to my ear and shake it gently. The sound of a wooden pin sliding is distinct—a soft, hollow thunk that tells you you’re on the right track.

Why Your First “Solve” Will Probably Be an Accident

There is a phenomenon I call the “Accidental Disassembly.” It usually happens when you’re fiddling with a puzzle while watching TV or talking to someone. Suddenly, the 6 Piece Wooden Puzzle Key ($12.99) falls apart in your lap, and you have no idea how you did it.

6 Piece Wooden Puzzle Key — $12.99

This is actually the best way to learn. The 6 Piece Wooden Puzzle Key is a masterclass in minimalism. When you stop overthinking the “how” and let your hands explore the “what,” the solution emerges. This is the essence of Wu Wei. Once the pieces are on the table, the real challenge begins: reassembly. I always tell people that taking a puzzle apart is only 10% of the job. Putting it back together is where you actually learn the geometry.

If your brain feels fried after a session of spatial reconstruction, taking a mental break with a digital numbers game can help reset your pattern recognition. Sometimes you need to step away from the 3D world to let the 2D logic settle.

The Peak Moment: The Logic of the Void

After testing everything from $5 stocking stuffers to $500 limited editions, I realized something that changed how I solve everything. You aren’t looking for the wood; you’re looking for the hole.

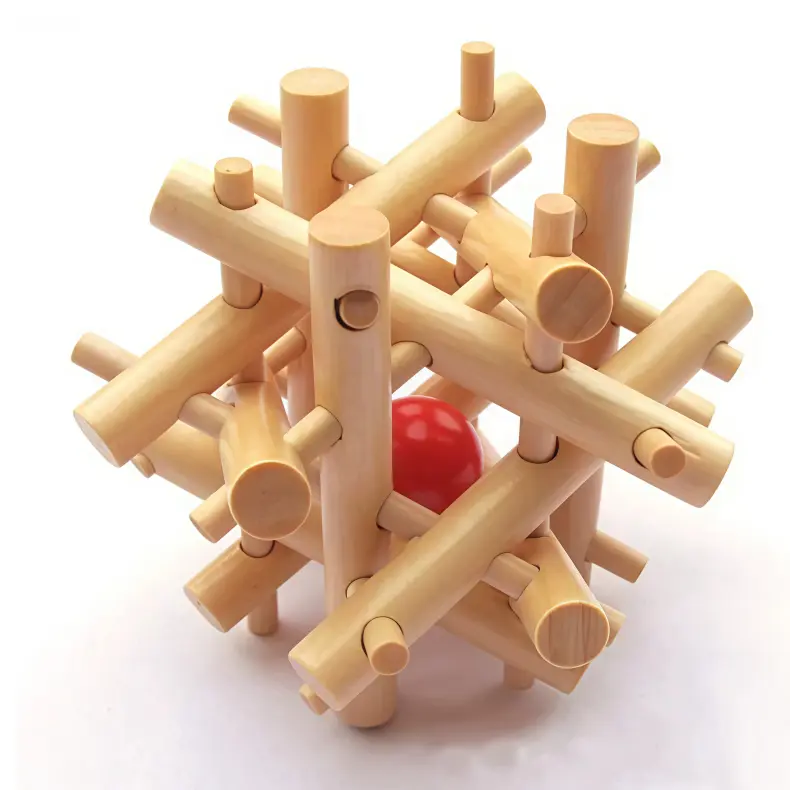

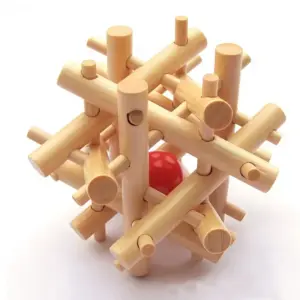

In a complex assembly like the Twelve Sisters Puzzle ($19.99), the “difficulty” is an optical illusion created by the density of the rods.

Twelve Sisters Puzzle

This is one of my favorite desk toys because it looks impossible. You have 12 thick rods, 12 interlocking sticks, and a crimson sphere in the center. Most people look at the 25 pieces and see chaos. But if you look at the negative space—the holes in the rods—the entire structure reveals itself. Each rod has five precision holes. The “solve” is simply aligning the voids so the sticks can pass through.

When I first sat down with the Twelve Sisters Puzzle, I spent an hour trying to force the sticks into place. Then I realized that if I positioned the central sphere first and built around the void, the rods practically fell into place. It’s a metaphor for life: focus on the gaps, the opportunities, and the structure takes care of itself. At just under twenty dollars, the tactile feedback of the thick rods is incredibly satisfying—it has a “heft” that cheaper puzzles lack.

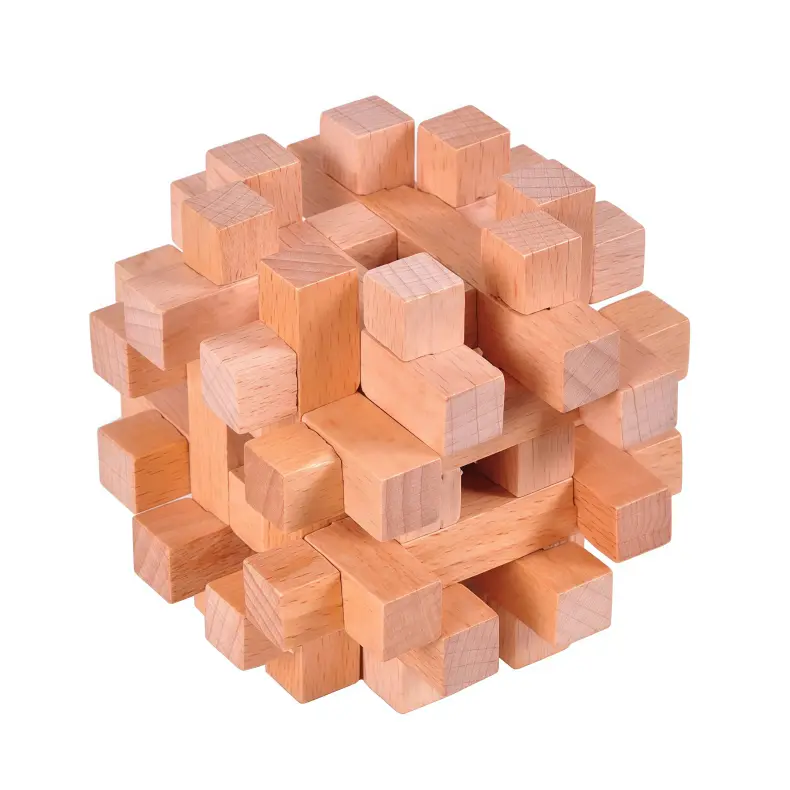

The Geometry of the Sphere: Luban vs. Molecular

Spherical puzzles are a different beast entirely. They don’t have the clear X-Y-Z axes of a burr. They require a “cradle” grip—holding the pieces together with three fingers of one hand while the other hand maneuvers the final locking piece.

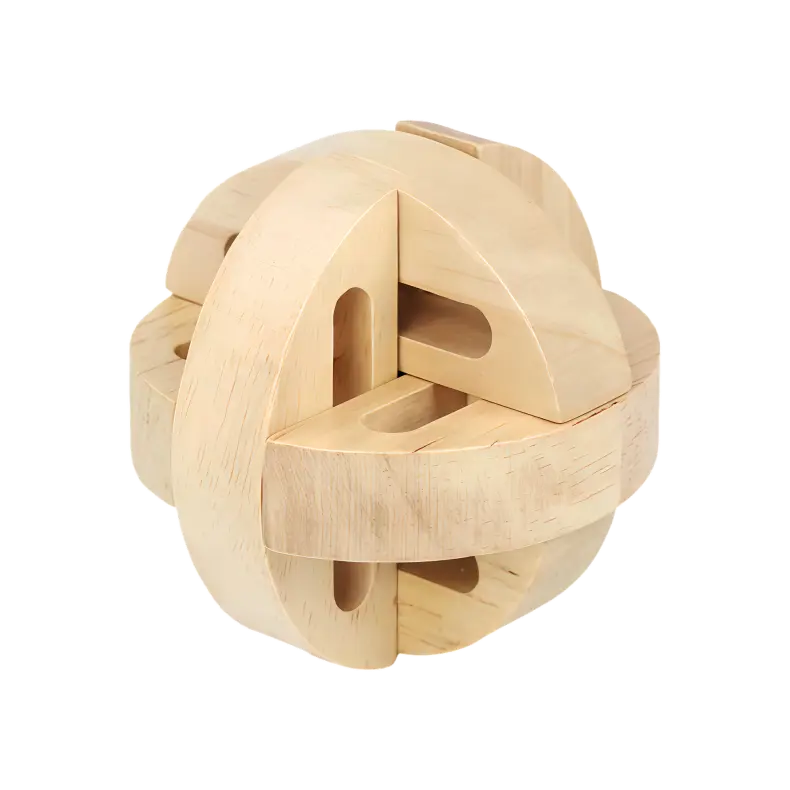

Luban Sphere Puzzle

The Luban Sphere Puzzle ($16.99) is a six-piece interlocking design that feels like a worry stone once solved. It’s smooth, fits in the palm, and has that classic “old world” aesthetic. The challenge here is that the pieces look identical, but they aren’t. One piece is the “master,” and if you don’t identify it, you’ll spend all afternoon trying to force a square peg into a round hole. I’ve had this on my desk for three weeks, and I still find the disassembly-reassembly process meditative. It’s not about the destination; it’s about the quiet wisdom of discovery.

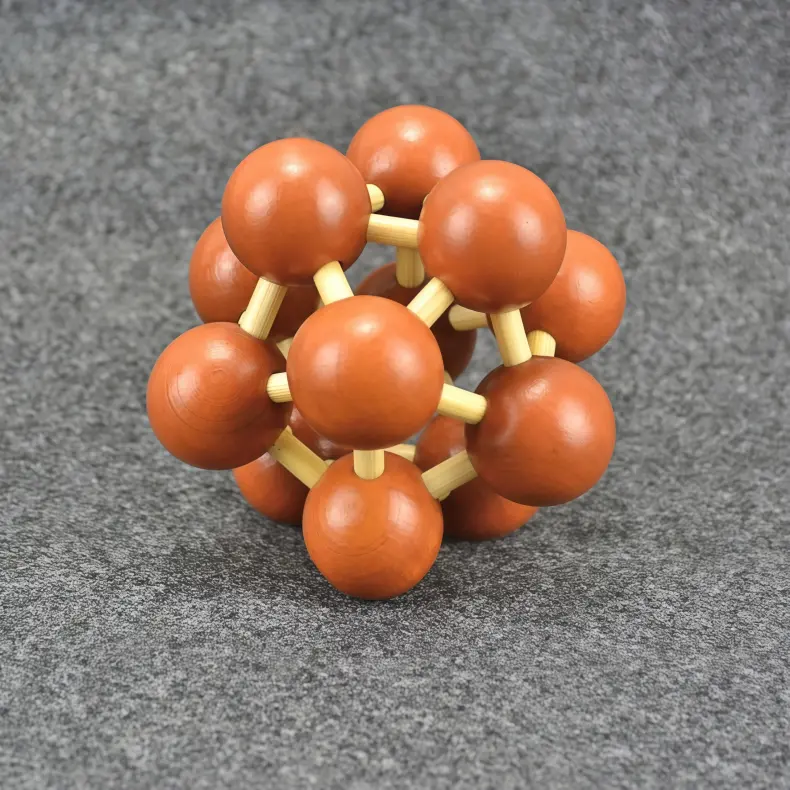

Compare that to the Molecular Ball Puzzle ($16.99), which uses rods and balls to create a similar shape.

Molecular Ball Puzzle — $16.99

The Molecular Ball Puzzle is less about “trick” movements and more about pure mechanical logic. It’s an excellent choice for someone who finds the “hidden key” style of puzzles frustrating. Here, everything is visible. It’s an honest challenge. If you enjoy this kind of structural building, you might also find that nostalgic gaming sessions offer a similar kind of “block-by-block” satisfaction.

When Wood Becomes a Lock: The Art of the “Key” Piece

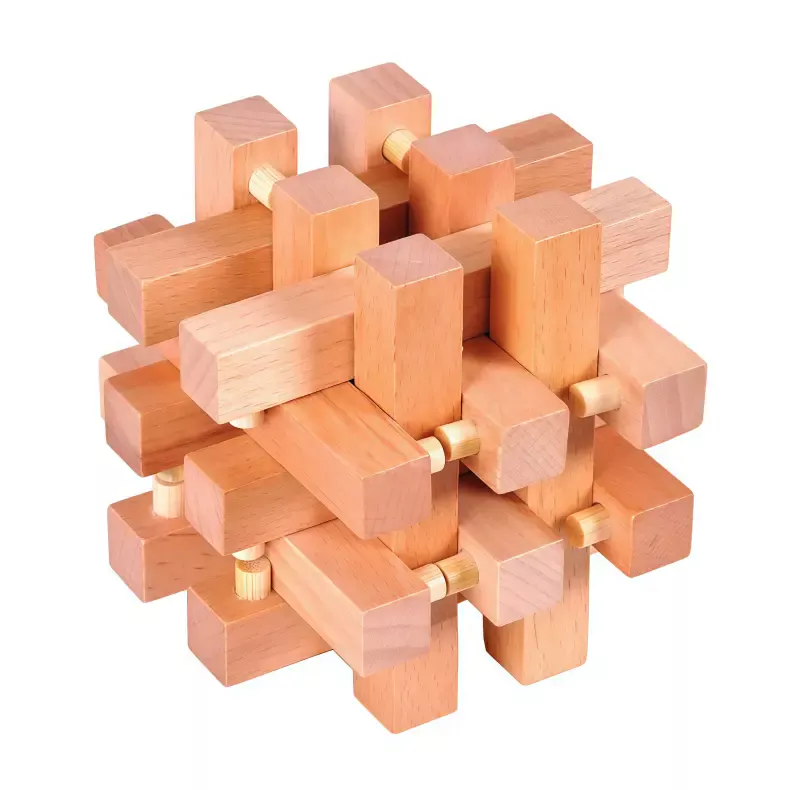

Some puzzles aren’t just shapes; they are mechanisms. The 18 Piece Wooden Puzzle ($16.99) is the “final boss” for many hobbyists.

18 Piece Wooden Puzzle

Seventeen identical pieces and one “key” piece. That is the formula for a headache if you aren’t prepared. The tolerances on this are tight—zero wiggle room. I’ve found that the best way to approach the 18 Piece Wooden Puzzle is to lay the pieces out in a grid first. You need to visualize the final cube before you start interlocking.

The “key” piece is usually slightly different in weight or has a microscopic chamfer on one edge. Finding it is the first victory. I once spent an entire Saturday afternoon with this puzzle, only to realize I had the “key” piece in my left hand the whole time. It teaches you that true knowledge reveals itself through action, not announcement. If you can solve this in under an hour on your first try, you have better spatial reasoning than 90% of the population.

The “Yield to Succeed” Principle

In the world of mechanical puzzles, we often talk about “The Tao of Solving.” This is most evident in the Double Cross Cage Puzzle ($18.88) and The Mystic Orb Lock ($16.99).

Double Cross Cage Puzzle

This thing is a beast. Twenty-four identical pieces that create a cage-like structure. It’s a tactile meditation on ancient wisdom. The strength of the cage comes from the geometric balance, not from glue or screws. When you try to pull it apart, it resists. But when you find the one piece that “yields,” the whole thing collapses with a very satisfying clatter. I’ve found that the finish on this wood is particularly smooth, which is important when you’re dealing with two dozen pieces that all need to slide simultaneously.

The Mystic Orb Lock

If the Double Cross is about strength, The Mystic Orb Lock ($16.99) is about vulnerability. It consists of six semi-circular pieces. Two of them are special locking pieces that control the whole structure. It’s a physical manifestation of the idea that there is always a “place where death cannot enter”—a hidden weakness that, when found, unlocks everything.

The move here is a “push-slide-snap” sequence. I’ve seen people try to pry this open with their fingernails, which is a great way to ruin a $17 puzzle. Instead, hold it loosely. Let the pieces settle. Often, the weight of the pieces themselves will reveal the gap. If you’re a fan of this kind of “hidden trigger” logic, the mental gymnastics required for trick boxes will feel very familiar to you.

The Wood Knot: A Philosophical Practice

Finally, we have the Wood Knot Puzzle ($16.99). This is the one I keep on my coffee table for guests.

Wood Knot Puzzle — $16.99

The Wood Knot Puzzle is pure geometric harmony. It embodies the Taoist teaching that “great form has no shape.” It looks like a solid knot of wood, but it’s actually six precisely crafted pieces. It’s a great “entry-level” puzzle because the solution is logical but not obvious. It’s the kind of object that makes people stop talking and start fiddling.

I’ve noticed that people who are good at jigsaw puzzles often struggle with the Wood Knot because they are looking for “edge pieces.” In 3D wooden puzzles, every piece is an edge piece. Every piece is a center piece. Everything is connected.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I know if a wooden puzzle is solved or just stuck?

If you have to apply more pressure than you would use to pop a grape, it’s stuck, not locked. Wood-on-wood friction is high, especially if the puzzle has been sitting in a humid environment. I’ve had puzzles “lock up” because the wood expanded by just a few microns. Try placing the puzzle in a dry, cool area for a few hours. If a piece still won’t budge, look for a sliding movement on a different axis. Never, ever use tools to pry a wooden puzzle apart.

What should I do if I lose the instructions?

Toss them anyway. Most wooden puzzle instructions are poorly translated or use diagrams that are more confusing than the puzzle itself. The real “instruction” is the symmetry of the pieces. If you’re really stuck, search for the puzzle’s name on YouTube or Reddit. The puzzle community is incredibly helpful. For instance, if you’re struggling with structural logic, navigating the nuances of secret compartments often uses similar interlocking principles that you can find explained in detail online.

Are wooden puzzles better than metal ones?

They are different. Metal puzzles, like those from the Hanayama series, are about precision and often involve “tricks” like hidden magnets or gravity pins. Wooden puzzles are about geometry and friction. Wood feels warmer in the hand and provides more tactile feedback, but metal is more durable. If you find yourself getting bored with wood, translucent geometry challenges can offer a nice change of pace.

My puzzle has a small “bulge” on one piece. Is it a defect?

Probably not. In many Chinese-style puzzles, a small protrusion or a slightly off-center hole is the “key” that allows the final piece to lock into place. Before you call it a manufacturing error, try to see if that bulge fits into a corresponding notch on another piece. These “defects” are often the most important part of the solve.

How do I maintain my wooden puzzles?

Keep them out of direct sunlight and away from high humidity. If a puzzle becomes too difficult to slide, you can use a tiny amount of dry lubricant like beeswax or a graphite pencil on the friction points. Avoid liquid oils, as they can cause the wood to swell and ruin the puzzle forever.

Are these suitable for children?

Most of the puzzles mentioned here, like the Luban Sphere Puzzle ($16.99), are great for kids aged 8 and up. They help build spatial reasoning and patience. However, puzzles with many small pieces, like the 18 Piece Wooden Puzzle ($16.99), might be frustrating for younger children. It’s better to start them with something like the Molecular Ball Puzzle ($16.99).

Why do some puzzles feel “loose” while others are tight?

This comes down to the tolerances of the manufacturing process. A loose puzzle is easier to solve but can feel “cheap.” A tight puzzle feels premium but can be frustrating if the wood expands. I personally prefer a slightly tighter fit, as it forces you to be more precise with your movements.

Can I solve these by just trial and error?

You can, but you won’t learn anything. Trial and error is the “brute force” method. The “elegant” method is to study the pieces, understand the locking mechanism, and then execute the solve in one continuous motion. If you find yourself just randomly moving pieces, stop. Take a breath. Try taking a mental break with a digital numbers game to clear your head, then come back and look for the pattern.

Is it okay to use a “cheat sheet” or video solution?

There’s no “cheating” in a solo hobby, but you do rob yourself of the “Aha!” moment. If you must use a guide, use it to get past the one piece you’re stuck on, then try to finish the rest yourself. The goal isn’t just to have a solved puzzle on your shelf; it’s to have a sharper brain.

Why are some wooden puzzles so much more expensive than others?

It usually comes down to the type of wood and the precision of the cuts. Hardwoods like rosewood or ebony are more expensive and harder to machine than softwoods like pine. A high-end puzzle will have perfectly flush seams, while a cheaper one might have visible gaps.

What is a “Burr” puzzle exactly?

A burr puzzle is an interlocking puzzle consisting of notched sticks, which combined make a three-dimensional, usually symmetrical object. The name “burr” likely comes from the finished puzzle’s resemblance to a seed burr. They are the foundation of traditional Chinese woodworking.

Can solving these puzzles help with memory or focus?

Absolutely. Solving mechanical puzzles engages both the left (logical) and right (creative) hemispheres of the brain. It requires sustained focus and “working memory” to keep track of the moves you’ve already tried. It’s a great way to unplug from the digital rush and practice mindfulness.

What if my puzzle is glued?

I’ve seen this on Reddit—someone buys a puzzle and thinks it’s glued because it won’t move. It’s almost never glue. It’s usually just friction or a very clever locking mechanism. If you suspect glue, look for residue around the seams. If there’s no residue, it’s just a very good puzzle.

How many pieces is too many?

For a beginner, 6 to 12 pieces is the sweet spot. Once you get to 24 pieces, like in the Double Cross Cage Puzzle ($18.88), the complexity increases exponentially. Don’t start with the 18 or 24-piece monsters unless you have a lot of patience.

Where can I find more advanced challenges?

Once you’ve mastered the basic interlocking designs, you should look into sequential discovery puzzles. These are puzzles that hide tools (like a small key or a pin) inside themselves, which you must find and use to unlock the next stage. They are the peak of the puzzle-solving world.

The One Puzzle That Teaches You How All the Others Work

If I had to go back to the beginning—back to that afternoon where I was frustrated by a simple six-piece cross—I would tell myself to start with the Luban Sphere Puzzle ($16.99). It’s the perfect baseline. It teaches you about symmetry, the “key” piece, and the importance of a gentle touch.

Wooden puzzles are a reminder that in a world of instant gratification and digital shortcuts, some things still require time, touch, and a little bit of silence. The “click” you hear when a final piece slides into place isn’t just wood hitting wood; it’s the sound of your brain finally aligning with the physical world.

If you’re ready to start your own collection, the Twelve Sisters Puzzle ($19.99) is my top recommendation for 2026. It’s beautiful enough to sit on a bookshelf and challenging enough to keep you occupied for a full Sunday afternoon. Once you’ve mastered the rods and sticks, the the mental gymnastics required for trick boxes will be your next logical step.

Put the phone down, clear your desk, and listen to the wood. The solution is already there; you just have to stop trying so hard to find it.