The first time I picked up a snake cube, it was February 2024. I was at a small hobbyist meetup in Vermont, and someone handed me what looked like a disorganized heap of wooden blocks held together by a prayer. “It’s a 3x3x3 cube,” they said. “Eventually.” Three hours later, after my coffee had gone cold and my fingers were slightly cramped from the tension of the elastic cord, the thing finally clicked into its final shape. I didn’t feel like a genius; I felt like I had just negotiated a peace treaty with a very stubborn piece of timber.

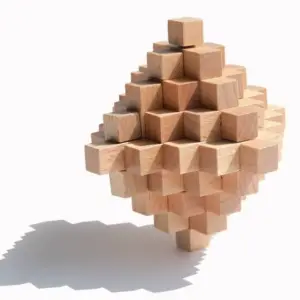

The snake cube is a deceptive beast. Unlike a Rubik’s Cube, where you’re rotating faces on fixed axes, the snake cube is a linear sequence of 27 small cubes connected by a single elastic string. To solve it, you aren’t just twisting; you are folding a one-dimensional line into a three-dimensional object. It is a lesson in spatial memory and the danger of “autopilot” solving. Most people fail because they try to force the pieces into a cube shape too early, ignoring the fact that the snake has its own internal logic—a “spine” that dictates exactly where every turn must happen.

The Anatomy of the Snake: Why Your Eyes Deceive You

Before you even attempt a fold, you need to understand what you’re holding. Every snake cube is composed of two types of pieces: “straights” and “corners.” A straight piece has the elastic string running through opposite faces. A corner piece has the string entering one face and exiting through an adjacent face at a 90-degree angle.

When you lay the snake out flat on your desk, you’ll notice a pattern of these corners and straights. This sequence is fixed. You cannot change the order. This is why the puzzle is actually a Hamiltonian path problem in graph theory—a path that visits every vertex exactly once. If you’re interested in the deeper mathematics behind how these paths are calculated, the Wikipedia entry on the Snake Cube offers a great breakdown of the permutations involved.

I’ve tested dozens of these, from cheap plastic versions that feel like they’ll snap to high-end hardwood versions. The tension of the internal cord is everything. If it’s too loose, the cube won’t hold its shape. If it’s too tight, you’ll feel like you’re fighting the wood. Finding that balance is key to a satisfying solve. This tactile feedback is something you also find in tactile magnets that snap into place, though the snake cube relies on friction rather than magnetism.

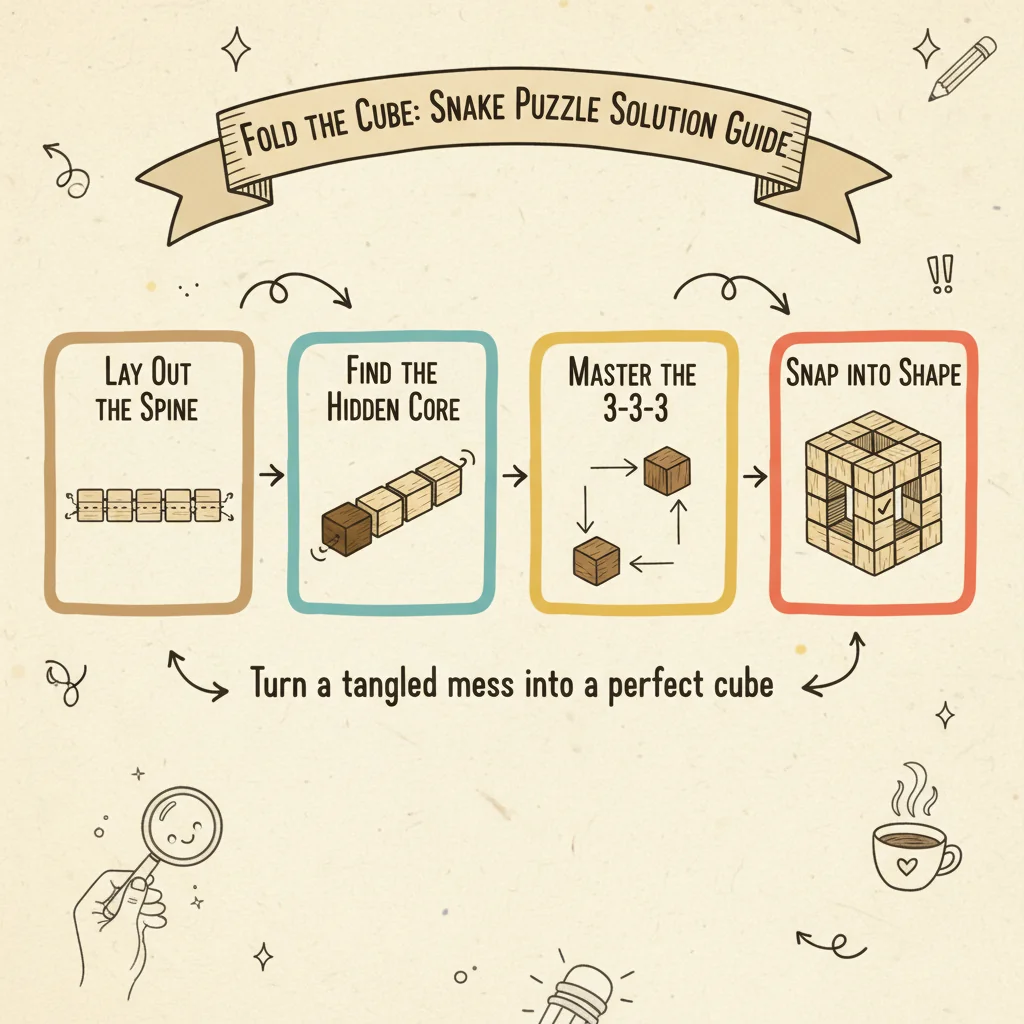

The “3-3-3” Strategy: Building the Foundation

The most common mistake is starting from the middle. You have two ends—two heads of the snake. One of them belongs in a corner of the finished cube, and the other belongs in the opposite corner. In my experience, the easiest way to solve this is to look for the longest “straight” sections. Most standard 3x3x3 snake cubes have a few sections where three cubes are in a straight line. These almost always form the edges of your 3x3x3 grid.

Start by identifying the “tail” that has a 2-cube straight section followed immediately by a corner. This is usually your starting block. You want to fold the snake so that you create a “U” shape with the first few pieces. This “U” will form the base layer. If you find yourself with a long tail of cubes and no way to turn them back into the main mass, you’ve likely missed a 90-degree pivot three or four steps back.

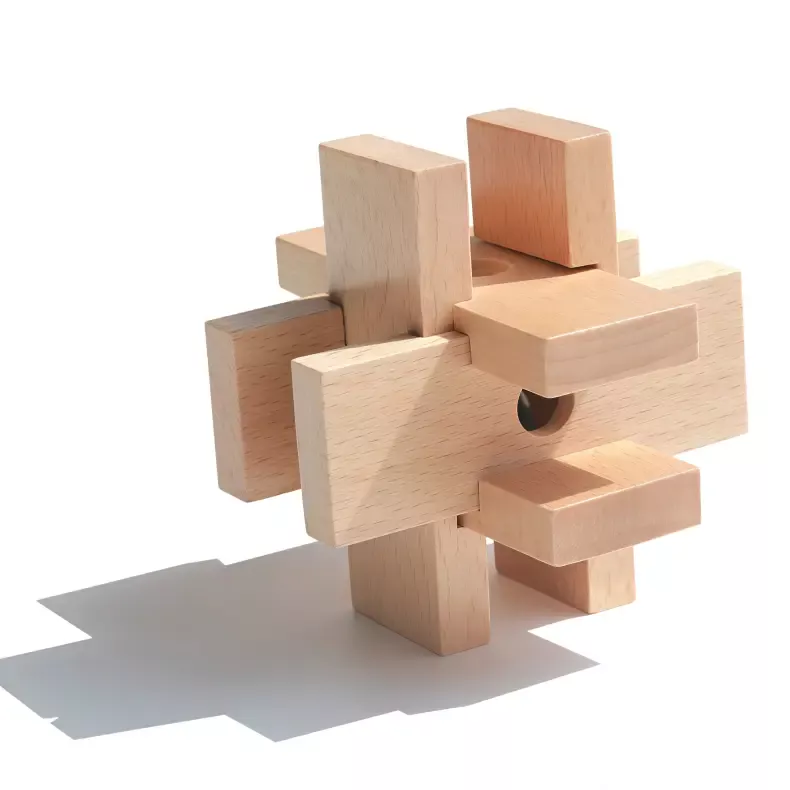

This process of visualizing the internal structure before you commit to a move is a hallmark of traditional Chinese engineering. It’s the same logic found in the Luban Lock Set 9 Piece, where geometry alone provides the structural integrity.

Luban Lock Set 9 Piece

This set, priced at $39.99, is essentially a masterclass in ancient joinery. While the snake cube uses an elastic cord to keep things together, these Luban locks rely on pure friction and mortise-tenon joints. I spent a rainy Saturday afternoon with the “Burr” style lock in this kit, and it’s a brutal reminder that modern puzzles often rely too much on “tricks” rather than pure spatial reasoning. Each of the nine puzzles in this set feels distinct—some are easy enough for a ten-year-old, while others will have a seasoned engineer questioning their career choices. The wood is unfinished and raw, which I prefer because it allows you to feel the grain as the pieces slide. If you can solve the entire set without looking at the solution sheet, you’ve officially graduated from “casual puzzler” to “obsessive.”

Why Your First Solve Will Probably Be an Accident

There is a specific moment in every snake cube solve where the pieces start to “clump.” You’ll have a 2x2x3 block formed, and you’ll feel a surge of hope. Then, you’ll realize the remaining six cubes are sticking out like a sore thumb with nowhere to go.

I call this the “Autopilot Trap.” We are conditioned to look for symmetry. We want the snake to fold neatly back and forth like a zig-zag. But the actual solution is often much more “loopy.” You might have to wrap the snake around the core you’ve already built. It’s a very different sensation than solving translucent challenges that rely on visual stacking, where you can see through the layers to understand the internal alignment. With the snake cube, the wood is opaque; you have to feel the path.

I’ve noticed that when I hand a snake cube to someone who plays the classic digital version of the slithering predator, they often try to move the “head” in a way that avoids the “body.” In the physical puzzle, the opposite is true: the head must constantly dive back into the body to fill the gaps.

The Peak Moment: Finding the “Core” Cube

After testing over 200 mechanical puzzles, I’ve found that almost every “impossible” challenge has a single “Aha!” moment. For the snake cube, that moment comes when you identify the 14th cube—the exact middle of the chain.

In a standard 3x3x3 solve, the middle cube of the chain almost always ends up as the center cube of one of the faces, or even the very center of the entire 3x3x3 block (the “heart” of the cube). Most people assume the center of the chain is just another piece, but if you can position that 14th cube correctly, the remaining two “tails” of the snake often fall into place with surprising ease.

I remember sitting on my porch last summer, struggling with a particularly stiff rosewood snake. I had been trying to solve it from the ends for forty minutes. I decided to stop, lay it flat, find the middle, and work outward from the center of the 3x3x3 grid. The puzzle was solved in under three minutes. It was like finding the key to a locking puzzle brain teaser—once you understand the internal mechanism, the external difficulty vanishes.

Comparing the Complexity: Wood vs. Metal vs. Motion

The snake cube belongs to a family of puzzles that prioritize “pathfinding.” While I love the tactile nature of wood, sometimes you need a break from the “fold and fail” cycle. If you’re feeling burnt out on the snake, I often recommend switching to a model kit. It uses the same spatial reasoning but with a clearer end goal.

For instance, the Galleon Ship 3D Wooden Puzzle Model Kit (check current pricing) requires you to think about how flat sheets of plywood become a curved hull. It’s a different kind of “fold.”

The Galleon is a desk-sized beast. Unlike the snake cube, which you can fiddle with while watching TV, the Galleon requires a dedicated workspace. The laser-cut waves and the rigging are surprisingly detailed. I found the assembly of the forecastle to be the most satisfying part—it’s where the engineering of the 16th century really shows through. It’s less of a “brain teaser” and more of a “patience tester.” If you enjoy the historical aspect of puzzles, this is a great companion piece to the Luban locks, as both celebrate the evolution of carpentry.

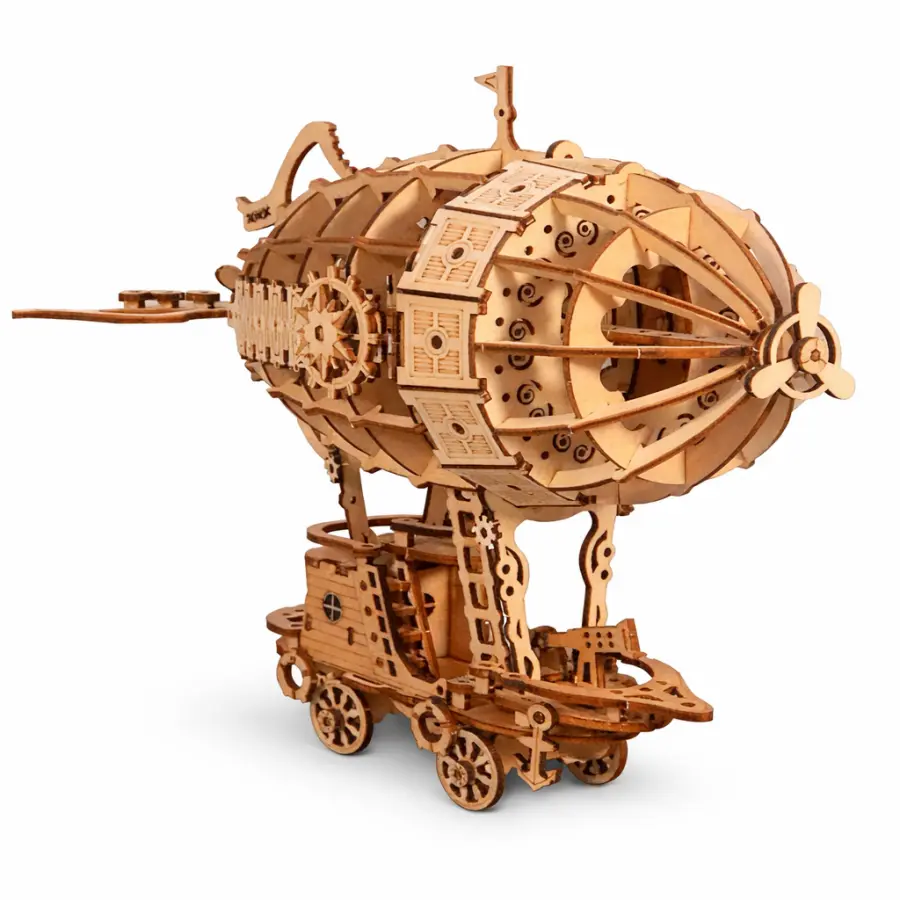

If you’re looking for something that moves once it’s finished, the Steampunk Airship 3D Wooden Puzzle ($26.66) is another excellent alternative.

I assembled this airship in about 70 minutes. It’s a 160-piece kit that leans heavily into the Victorian aesthetic. The spinning propeller is the highlight here. What I appreciate about this kit is that it doesn’t try to be overly complex; it’s a straightforward build that results in a great conversation piece. It’s a nice palette cleanser after a week of trying to solve the snake cube.

Advanced Techniques: The “Right-Hand” Rule

If you’re still stuck on the snake, try starting from the other end. This sounds like basic advice, but because of how the corner pieces are oriented, one end of the snake is often “easier” to visualize than the other. Reddit users in the r/puzzles community have often noted that piece 22 (counting from the left) is a frequent culprit for errors. If you start from the right, piece 22 becomes piece 5, making it much easier to track its position in the final 3x3x3 grid.

This kind of strategic positioning on a grid is exactly what you need to master the snake. You aren’t just moving pieces; you’re occupying coordinates.

6 Piece Wooden Puzzle Key

At $12.99, this is one of the most affordable “gateways” into the world of interlocking puzzles. It’s a small, hardwood “key” made of six pieces. The philosophy here is “Wu Wei”—effortless action. If you find yourself forcing the pieces of the snake cube, you’re doing it wrong. This key puzzle teaches you that same lesson. When the pieces are aligned correctly, they slide together with zero resistance. If you have to push, you’ve made a mistake. I keep one of these on my coffee table; it’s the perfect thing to hand to a guest who says, “I’m good at puzzles.” Watching them struggle with six simple pieces of wood is a reminder that complexity is often an illusion.

The Sensory Experience: Why Wood Matters

There is a reason the snake cube is almost always made of wood. The “clack” of the cubes as they hit each other and the slight resistance of the elastic cord create a sensory loop that plastic simply can’t replicate. It’s a meditative practice.

For those who want a break from the organic feel of wood, there are crystal alternatives that offer a completely different tactile experience. The 3D Crystal Rose Puzzle ($19.99) and the 3D Crystal Apple Puzzle ($18.88) are great examples.

3D Crystal Rose Puzzle — $19.99

The Crystal Rose is a 44-piece translucent challenge. I’ll be honest: I usually prefer wood, but there’s something about the way this catches the light on a windowsill that makes it worth the hour of assembly. It’s less about “solving” and more about “stacking.” It’s a great gift for someone who finds the traditional wooden puzzles a bit too “stuffy.”

3D Crystal Apple Puzzle — $18.88

Similarly, the Crystal Apple is a solid desk accessory. It’s also 44 pieces and stands about the size of a real Gala apple. The difficulty is low, but the visual payoff is high. I gave one of these to my daughter’s teacher last year, and it’s still on her desk. It beats another “World’s Best Teacher” mug any day of the week.

Comparison of Top Mechanical Challenges

To help you decide which path to take, I’ve put together this quick comparison of the spotlight products we’ve discussed.

Beyond the Snake: Exploring Interlocking Puzzles

If you’ve managed to solve the snake cube, you’ve essentially mastered the concept of “interlocking geometry.” The logical next step is the world of Burr puzzles. These are the “boss level” of wooden brain teasers.

Six-Piece Burr Puzzle

This $17.99 puzzle is the quintessential brain teaser. It’s based on Daoist principles of balance and non-force. When I first tried a six-piece burr, I spent twenty minutes trying to pull it apart before I realized that one piece slides in a direction I hadn’t even considered. It’s a great follow-up to the snake cube because it removes the elastic cord. There is no “safety net.” If you let go of the pieces before they are locked, the whole thing collapses. It’s high-stakes puzzling for the patient mind.

Interlock Puzzle Sphere

Also priced at $17.99, the sphere is the “final exam” of this category. It takes the six-piece burr concept and applies it to a curved surface. This is significantly harder than the snake cube because the pieces don’t have flat edges to guide your eyes. You have to rely entirely on the internal notches. I’ve found that this puzzle is the ultimate “ego-checker.” You think you’re good at puzzles until you’re holding five pieces of a sphere and can’t find where the sixth one fits. The wood is smooth and has a weight to it that makes the eventual “click” of the final piece incredibly rewarding.

For a more artistic approach to the same mechanical principles, I often point people toward the 3D Wooden Cello Puzzle Model Kit ($29.99).

The Cello isn’t a “puzzle” in the sense that you take it apart and put it back together, but the assembly process is a puzzle in itself. It uses Victorian-style mechanical gears and intricate engravings. Research has shown that these types of visuospatial activities support cognitive health, and building something as elegant as a cello certainly feels like a workout for the brain.

FAQ: Everything You Wanted to Know About Snake Cubes

How many steps does it take to solve a 3x3x3 snake cube?

A standard solution usually involves 16 to 18 distinct “folds.” However, because each fold can involve rotating a section of the snake multiple times to find the right orientation, the actual number of movements is much higher. I usually tell people to expect about 50 individual twists for their first successful solve. If you’re looking for a faster “fix,” you might enjoy the DIY Castle Music Box Night Light Shadow Box Kit ($33.99), which offers a more linear, step-by-step assembly process.

Are all snake cubes the same?

No. While the 3x3x3 is the most common, there are 4x4x4 and even 5x5x5 versions. Furthermore, the internal sequence of “straights” and “corners” can vary. There are actually over 100,000 possible Hamiltonian paths for a 3x3x3 grid, though only a handful are used for commercial puzzles. If you find a “unique” snake, you can’t rely on standard YouTube tutorials. You have to map the sequence yourself. This is the ultimate test of mechanisms that hide their secrets.

What do I do if the elastic string snaps?

Sadly, if the string snaps, the puzzle is usually toast. You can try re-stringing it with a heavy-duty elastic cord and a long needle, but getting the tension right is nearly impossible without factory tools. This is why I always tell people: never force a turn. If the wood is resisting, it’s because you’re trying to make an illegal move.

Is there a mathematical formula for the solution?

Yes, but it’s not something you can do in your head. Computer scientists use backtracking algorithms to solve these. They represent the snake as a string of characters (L for Left, R for Right, U for Up, etc.) and let a script find the path that doesn’t intersect itself. For us humans, it’s better to rely on landmarks—like the 3-cube straight sections I mentioned earlier.

Can a child solve a snake cube?

The snake cube is generally rated for ages 8 and up. However, it requires a level of frustration tolerance that many adults lack. If you’re looking for something for a younger child, I’d suggest starting with something more visual, like the 3D Crystal Apple Puzzle ($18.88), which is much more forgiving.

How do I store my snake cube?

Always store it in its solved “cube” state. Leaving it as a long “snake” for months can actually cause the elastic cord to lose its “memory,” leading to a loose, floppy puzzle that won’t stay together when you finally do solve it.

Why is my snake cube “impossible”?

Check piece 22. As mentioned in the Reddit “User Voice” section, there are some rare variants where the sequence is slightly different, making the standard “U-wrap” solution fail. If you’re stuck, try starting from the opposite end of the snake. Sometimes the “head” and “tail” are swapped in the manufacturing process.

Is the snake cube related to the Rubik’s Cube?

Only in name and shape. The Rubik’s Cube was invented by Ernő Rubik in 1974. He also invented the Rubik’s Snake, which is a different beast entirely—it’s made of triangular prisms and doesn’t have an internal cord. The wooden snake cube is a traditional design that predates the 1970s “cube craze.”

Does solving puzzles actually make you smarter?

While I’m not a doctor, I can tell you that my focus and patience have improved significantly since I started this hobby. It’s about building “cognitive endurance.” If you can sit with a piece of wood for two hours without checking your phone, you’re already ahead of most people.

What’s the best wood for a snake cube?

I prefer Samanea Saman (Monkey Pod wood). It’s durable, has a beautiful two-tone grain, and holds up well to the friction of the cubes rubbing against each other. Avoid the painted versions; the paint eventually chips and gets into the internal mechanism, making the turns feel “crunchy.”

The One Puzzle That Teaches You How All the Others Work

Whenever I’m asked where someone should start their collection, I always point back to the basics. The snake cube is a rite of passage. It’s the bridge between simple toys and complex mechanical engineering. It teaches you that the solution isn’t always a straight line—sometimes you have to go backward to go forward.

After years of fiddling with these, I’ve realized that the frustration is the point. The moment of “Aha!” only exists because of the forty minutes of “Oh no.” If you’re ready to start your own journey into the world of mechanical enigmas, start with the 6 Piece Wooden Puzzle Key ($12.99). It taught me more about the philosophy of problem-solving than any textbook ever could. It’s a quiet, humble little object that rewards observation over brute force.

Once you’ve mastered the key and tamed the snake, you’ll find that you start seeing the world a bit differently. You’ll look at a bridge or a building and see the “locks” and “straights” that hold it together. And that, more than any solved cube on a shelf, is the real prize. If this clicked for you, the world of sequential discovery is the next logical step in your obsession.

The wood doesn’t lie; it only waits for you to understand it.