The third time the smallest cherry-wood disc slipped from my fingers and rolled under the radiator, I didn’t swear. I just sat there on the floor of my home office, staring at the three empty pegs, and realized I had forgotten move 114 of a 255-move sequence. That is the reality of the Tower of Hanoi. It is a puzzle that looks like a toddler’s stacking toy but possesses the mathematical teeth of a graduate-level recursion exam. After testing over 200 mechanical puzzles in my life, I’ve found that few things expose a person’s psychological hardware quite like these wooden rings.

The Tower of Hanoi is more than a desk toy; it is a diagnostic tool for your own patience. The thesis I’ve landed on after years of fiddling is this: The best wooden puzzles don’t just challenge your logic—they punish your ego and reward your rhythm. While digital versions of this game exist on every smartphone, they lack the “cost” of a physical mistake. When you’re moving actual timber, every error has weight. You feel the friction of the wood, the slight wobble of the pegs, and the mounting pressure of a stack that is supposed to be on the right, but is currently stuck in the middle.

The Legend of the 64 Golden Discs

Most people encounter the Tower of Hanoi in a computer science class or a doctor’s waiting room, but its history is steeped in a 19th-century marketing stunt that would make modern influencers jealous. In 1883, the French mathematician Édouard Lucas introduced the puzzle to the public under the pseudonym “N. Claus de Siam” (an anagram of Lucas d’Amiens). He accompanied the toy with a legend about the Temple of Brahma in Benares.

According to the story, priests were tasked with moving 64 golden discs from one diamond needle to another, following the same three rules we use today. The catch? Once the last disc is moved, the world will end in a thunderclap. Mathematically, 64 discs require $2^{64}-1$ moves. Even at one move per second, it would take roughly 585 billion years to finish. Britannica notes that this legend likely originated with Lucas himself to add a layer of mystique to his invention.

When you hold a tower of hanoi wooden puzzle, you aren’t just playing a game; you are engaging with a piece of mathematical folklore. The wood feels grounded, unlike the hypothetical gold of the Benares priests. I’ve found that the tactile feedback of a well-sanded peg makes the repetitive nature of the solve feel less like a chore and more like a meditative exercise.

Why Wood Beats Plastic for Recursive Logic

There is a specific “clack” that occurs when a wooden disc settles onto its new home. It’s a sound that signifies a commitment. In the digital versions, you can “undo” a move with a flick of a finger. In the physical realm, moving an eight-ring stack requires a physical investment of about ten minutes of focused work. If you mess up on move 200, you can’t just hit Ctrl+Z. You have to live with the mess or start over.

This physical cost is exactly what makes wooden puzzles superior for learning. You start to notice the cognitive benefits most puzzle sellers won’t mention, such as the development of “muscle memory” for recursive patterns. After the first 50 moves, your brain stops calculating “$2^n-1$” and your hands start to recognize the dance. It becomes a flow state.

The Architecture of Frustration: How the Rules Change You

The rules are deceptively simple:

1. Only one disc can be moved at a time.

2. Each move consists of taking the upper disc from one of the stacks and placing it on top of another stack or on an empty peg.

3. No larger disc may be placed on top of a smaller disc.

These constraints create a bottleneck. You quickly realize that to move the largest disc at the bottom, you first have to move every single disc above it to the “spare” peg. This is the essence of recursion. You solve a small version of the problem to solve a slightly larger version, repeating this until the entire tower has migrated.

I’ve watched engineers spend thirty minutes overcomplicating the logic, while my ten-year-old nephew figured out the alternating pattern in five. The puzzle doesn’t care how smart you are; it only cares how disciplined you are. This discipline is a common thread in other traditional designs, like the Luban Cube Puzzle, which costs $21.99 and requires a similar “one-way-only” logic to assemble.

Beyond the Rings: Expanding the Wooden Arsenal

If you’ve mastered the 8-ring Hanoi, you might think you’ve “solved” wooden puzzles. You haven’t. You’ve just finished the prologue. The Tower of Hanoi is a linear challenge—a sequence. The next step in a collector’s journey usually involves interlocking puzzles, where the challenge isn’t just the sequence, but the spatial geometry.

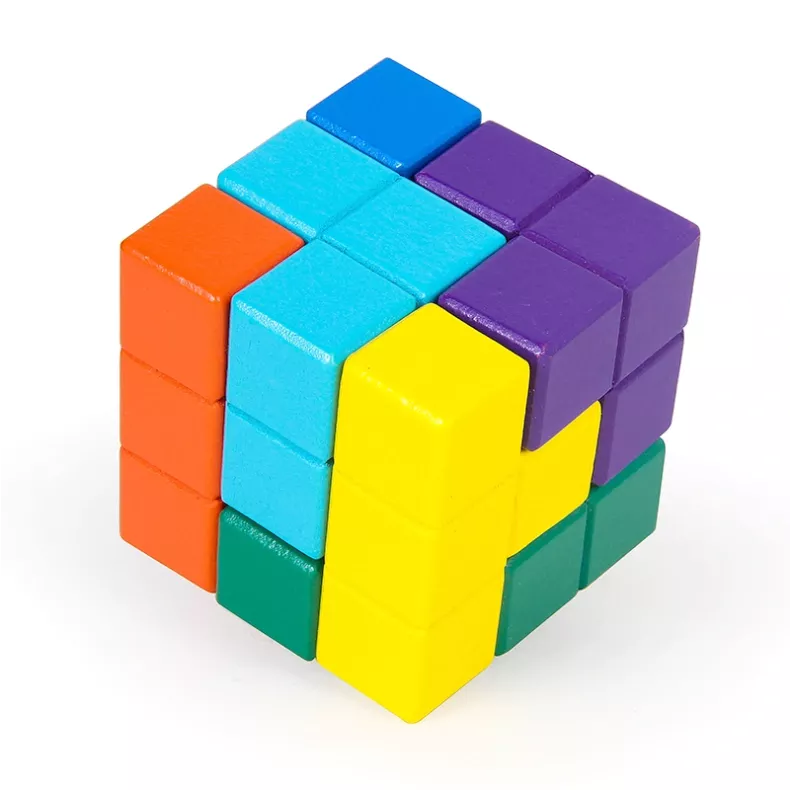

Luban Cube Puzzle

The Luban Cube Puzzle ($21.99) is the natural successor for anyone who found the Tower of Hanoi too “flat.” While Hanoi lives in a 2D plane of three pegs, this cube forces you into 3D spatial reasoning. It’s based on ancient Chinese mortise-and-tenon joinery—the same stuff that keeps temples standing without a single nail. When I first tried to reassemble this 3×3×3 block, I realized I had been relying too much on visual patterns and not enough on structural logic. Every piece has exactly one home. If you force it, you’re doing it wrong. It’s a beautifully sanded piece of hardwood that feels substantial in the hand, and at just over twenty dollars, it’s a steal for the sheer amount of “wait, how did I do that?” moments it provides.

The Barrel Luban Lock

For something that feels a bit more “finished” on a coffee table, The Barrel Luban Lock ($19.77) is my go-to recommendation. It’s a six-piece interlocking puzzle that forms a smooth, tactile barrel. The tolerances are surprisingly tight for a mass-produced wooden item. I’ve had this on my desk for three weeks, and it’s the one guests always pick up first. Unlike the Tower of Hanoi, which is a test of memory, the Barrel is a test of observation. You have to find the one “key” piece that slides out to release the others. It’s a lesson in the hidden mechanics of sequential discovery that defines the higher-end hobbyist market.

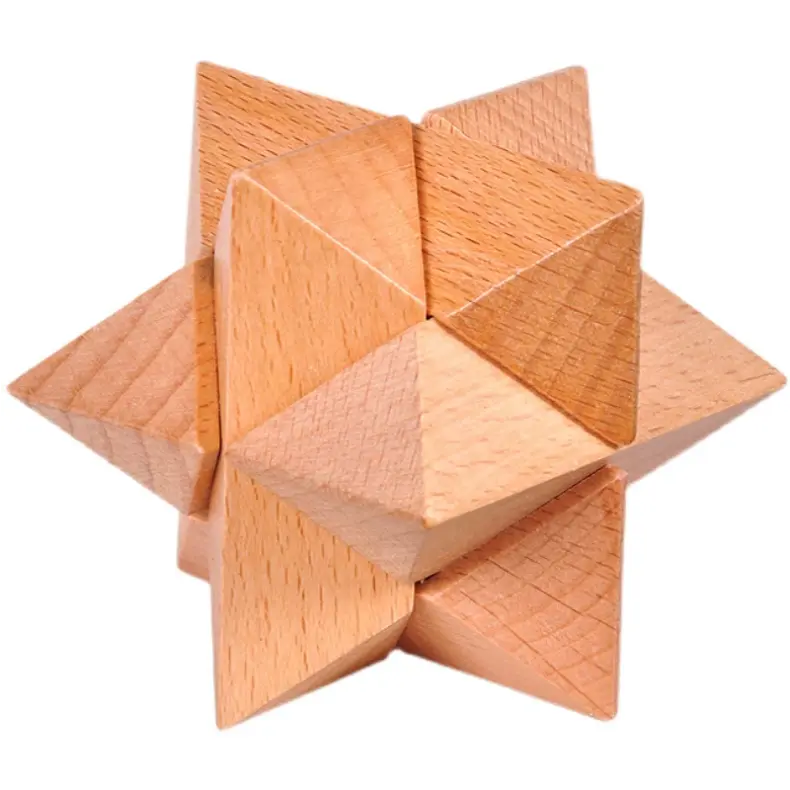

Kongming Ball Lock

If you prefer curves over corners, the Kongming Ball Lock ($20.99) is a sphere of frustration and joy. It uses a similar interlocking joint system as the cube, but the spherical shape makes it much harder to orient the pieces. I’ve found that this specific puzzle is great for people who tend to “brute force” their way through problems. The wood is polished to a high sheen, and if you try to pull it apart with too much strength, the friction will lock the pieces even tighter. It demands a gentle touch. It’s a fantastic example of the “Kongming” style, named after the legendary strategist Zhuge Liang.

The Peak: The Moment the Recursion Clicks

There is an unforgettable moment that happens to every serious Hanoi solver—usually around the fifth or sixth ring. I call it the “Recursive Epiphany.”

I was testing a premium 9-ring set last winter. For the first hour, I was counting moves in my head: Small to C, Medium to B, Small to B… It was exhausting. Then, somewhere around move 80, my brain just stopped “thinking” and started “seeing.” I realized that I wasn’t moving individual discs anymore; I was moving sub-towers. To move a 4-stack, I just had to move a 3-stack out of the way.

This is the “Peak” of the experience. It’s the transition from tactical thinking to strategic intuition. I handed the same puzzle to a mechanical engineer friend, and he immediately started drawing a tree diagram. Meanwhile, my neighbor—a professional drummer—solved it by finding the beat. This side-by-side comparison proved to me that the Tower of Hanoi isn’t a math puzzle; it’s a rhythm puzzle.

If you find yourself stuck in that “counting” phase, take a break. Go play a quick mental reset with digital classics to clear your head. When you come back to the wood, stop thinking about the numbers and start thinking about the shapes.

Balancing the Mind: Yin, Yang, and Geometric Harmony

Many of the puzzles I’ve reviewed lately bridge the gap between “toy” and “meditation tool.” The Tower of Hanoi has that repetitive, rosary-bead quality to it. Other puzzles in my collection take this philosophical angle even further.

Yin-Yang Taiji Lock

The Yin-Yang Taiji Lock ($15.88) is a four-piece challenge that embodies the concept of balance. It’s not particularly difficult—I solved it in about ten minutes—but that’s not really the point. The pieces are carved from aged hardwood and fit together with a satisfying “thunk.” It’s a meditative object. It’s the kind of thing you fiddle with while on a long Zoom call when you need to keep your hands busy so your mind can focus. It’s a reminder that sometimes the solution isn’t about complexity, but about finding how two opposing shapes can become a single circle.

7 Color Soma Cube Puzzle

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the 7 Color Soma Cube Puzzle ($21.88). While the Taiji lock is about simplicity, the Soma Cube is about infinite variety. It consists of seven non-convex polycubes that can be assembled into a 3×3×3 cube in 240 different ways. I’ve spent more time with this than almost any other puzzle on my shelf because it never feels “done.” Once you solve the cube, you start trying to build the “dog,” the “castle,” or the “sofa.” It’s a vibrant, tactile explosion of color that stands out against the more traditional wood-toned puzzles. It’s particularly good for developing the strategic depth of positional play often found in complex board games.

Why Quality Matters: The “Cheap Wood” Warning

I’ve bought $5 Hanoi towers from discount bins, and I’ve bought $100 artisan versions. The difference isn’t just in the aesthetics; it’s in the tolerances. If the pegs are too loose, the discs wobble and fall off. If the holes are too tight, the wood expands with humidity and the puzzle becomes literally unsolvable.

When looking for a tower of hanoi wooden puzzle, look for “sanded” and “unfinished” or “lightly waxed” wood. Heavy lacquer can make the discs sticky. You want a smooth glide. This same rule applies to interlocking puzzles like the

Luban Sphere Puzzle — $16.99

Luban Sphere Puzzle ($16.99). If the six interlocking pieces aren’t precision-cut, the sphere will feel “crunchy” when you try to disassemble it. A good wooden puzzle should feel like it was grown into its shape, not forced.

Inline Mentions of the Arsenal

For those who want a varied collection, I often suggest throwing in a few “quick solves” to balance out the heavy hitters. The

Wood Knot Puzzle — $16.99

Wood Knot Puzzle 2 ($16.99) is a classic six-piece cross that teaches you the basics of “key” pieces. If you enjoy that, the

Mortise-and-Tenon Soccer Ball Puzzle ($16.89) offers a similar challenge but with a much more complex external geometry.

For history buffs, the

Fuxi Eight-Corner Puzzle Ball ($19.99) is a beautiful conversation piece inspired by the “three-three” principle of Chinese mythology. And if you’re traveling, the

Big Three-Link Wooden Puzzle ($17.88) is durable enough to survive being tossed in a carry-on bag without losing its pieces.

Comparison of Top Wooden Challenges

FAQ: Everything You Wanted to Ask About Tower of Hanoi

How many moves does it take to solve an 8-ring Tower of Hanoi?

The formula for the minimum number of moves is $2^n – 1$, where $n$ is the number of discs. For an 8-ring tower, that’s $2^8 – 1$, which equals 255 moves. If you make even one mistake, that number can easily double as you try to backtrack. Most people assume they can “wing it,” but without understanding the recursive nature of the puzzle, you’ll likely get stuck in a loop. It’s a great lesson in efficiency.

Is the Tower of Hanoi good for kids?

Absolutely, but start small. A 3-ring or 4-ring tower is perfect for ages 5-8. It teaches them about size ordering and basic strategy. Once they hit 6 rings, it becomes a test of focus. I’ve seen kids use these wooden towers to learn about visual logic of crystalline structures and other geometric concepts without even realizing they’re “studying.” For adults, it’s more of a mental endurance test.

What is the “God’s Algorithm” for the Tower of Hanoi?

The most efficient way to solve it is to move the smallest disc on every odd-numbered move. On even-numbered moves, there is only one other legal move possible. If you follow this simple alternating rhythm, you will always reach the solution in the minimum number of moves. The challenge, of course, is remembering which direction to move the smallest disc (it depends on whether the total number of discs is even or odd).

Why do some versions have different colored rings?

While the classic version uses natural wood, colored rings are often used as a “training wheels” mechanism. It helps the brain track which disc is which in a high-ring-count stack. However, purists (myself included) prefer the uniform wood look. It forces you to rely on size recognition rather than color coding, which is a more pure form of the challenge.

Can the Tower of Hanoi be “unsolvable”?

Not if the rules are followed. It is mathematically proven to be solvable for any number of discs. However, if a peg is broken or a disc is missing, the logic breaks down. This is why I stress buying high-quality wood. If a peg snaps during a move, your 255-move journey ends in a very annoying trip to the hardware store.

How does the Tower of Hanoi relate to computer science?

It is the “Hello World” of recursion. It’s used to teach students how a large problem can be broken down into identical smaller problems. If you can solve a 3-disc tower, you can technically solve a 100-disc tower—you just need more time. This concept of self-similarity is a fundamental building block of modern software engineering.

Is wood better than metal for this specific puzzle?

For Hanoi, yes. Metal discs tend to be noisy and can be slippery. Wood has a natural “grip” that makes stacking easier. However, for interlocking puzzles, metal often allows for tighter tolerances. I’ve reviewed dozens of metal cast puzzles that are incredible, but for the Tower of Hanoi, the warmth of wood is unbeatable.

How do I clean a wooden puzzle?

Never soak it. Use a slightly damp microfiber cloth to wipe away dust and skin oils. If the wood starts to feel “dry” or the pieces don’t slide well, a tiny amount of food-grade mineral oil or beeswax can restore the finish. Avoid furniture polish, as the scents can be overpowering when you’re holding the puzzle close to your face for an hour.

What’s the best age to start with complex interlocking puzzles?

Most “Luban” style locks are rated for 8+, but that’s more about the fine motor skills required to not drop the pieces. Intellectually, they can challenge anyone from 8 to 80. I’ve found that seniors particularly enjoy the Yin-Yang Taiji Lock ($15.88) because it’s tactile and rewarding without being frustratingly difficult.

Why is it called “Kongming”?

It’s named after Zhuge Liang (styled Kongming), a legendary chancellor and strategist of the Three Kingdoms period in China. While there’s no historical proof he invented these specific wooden locks, the name carries the weight of “genius-level strategy.” It’s a bit of ancient branding that has survived for nearly two thousand years.

Can these puzzles help with ADHD or anxiety?

I am not a doctor, but I can tell you from personal experience that “fidgeting” with a purpose is incredibly grounding. The Tower of Hanoi requires enough focus to quiet the “background noise” of a busy brain, but it’s repetitive enough to be soothing. It’s a form of active meditation.

What happens if I lose a piece?

This is the tragedy of wooden puzzles. Unlike a deck of cards, you can’t really play with an incomplete set. I keep my “active” puzzles on a lipped tray so pieces can’t roll away. If you do lose a piece of something like the 7 Color Soma Cube Puzzle ($21.88), you’ve essentially turned a puzzle into a collection of very pretty wooden blocks.

Are these puzzles sustainably sourced?

Most reputable sellers, including tea-sip.com, use sustainably sourced hardwoods like maple, walnut, or bamboo. Wood is naturally more eco-friendly than plastic, and a well-made wooden puzzle can last for decades, whereas plastic ones often end up in a landfill when a peg snaps.

Why are some puzzles so much more expensive than others?

It comes down to labor and precision. A puzzle with six pieces that all look identical but have different internal notches requires much higher machining standards than a simple stacking toy. You’re paying for the “fit.” If the pieces don’t slide perfectly, the puzzle is a failure.

What should I buy after the Tower of Hanoi?

If you liked the sequential nature, go for a puzzle box. If you want to test your spatial skills, get the Luban Cube Puzzle ($21.99). It’s the perfect “Level 2” for any budding enthusiast.

What 40 Hours of Timber and Tension Actually Taught Me

After a few decades of this hobby, I’ve realized that the Tower of Hanoi is the “North Star” of the puzzle world. It’s the one we all go back to when we want to remember why we started. It doesn’t hide its secrets behind trick panels or magnets; it lays everything out in the open and simply asks, “Do you have the discipline to finish?”

If you’re sitting there with a messy desk and a wandering mind, start with the Luban Cube Puzzle ($21.99). It taught me more about patience in one afternoon than any “self-help” book ever could. There is a profound satisfaction in the moment the last piece of wood slides into place—a click that you feel in your bones as much as you hear with your ears.

The journey of a puzzle enthusiast usually starts with a simple stack of rings and ends with a shelf full of complex enigmas. If this clicked for you, the hidden mechanics of sequential discovery go deeper into how these objects can actually change the way you perceive physical space. Don’t rush the solve. The reward isn’t the completed tower; it’s the quiet, focused version of yourself you find along the way.