There is a moment, familiar to anyone who has ever tried to assemble furniture without instructions, when the parts refuse to cooperate. You rotate a piece. Flip it. Try forcing it. Nothing. And then—without any new information—it clicks. The angle was always there. You just had to stop overthinking.

That moment has a lineage stretching back at least six centuries, to a manual that codified the exact dimensions, rituals, and hard-won logic of Chinese architectural joinery. The text is called the Lu Ban Jing—roughly, “The Classic of Lu Ban”—and it is one of the strangest technical documents ever written. Half of it reads like an engineering specification. The other half reads like a horoscope for buildings. Together, they reveal something that modern makers are only now rediscovering: precision and intuition are not opposites. They are collaborators.

The Carpenter Who Became a Legend

Lu Ban himself is a figure wrapped in more myth than sawdust. Tradition places him around 507 BCE in the state of Lu, during the fractious Spring and Autumn period. He is credited with inventing the saw (after cutting his hand on serrated grass), the carpenter’s square, the ink line, and—depending on which account you trust—a wooden bird that flew for three days straight.

The real Lu Ban, if a single man existed behind the name, was likely a master craftsman whose techniques became the template for generations of builders. But the manual that carries his name was compiled much later, during the Ming dynasty, probably in the fifteenth century. It gathered centuries of workshop knowledge—measurements, joinery methods, furniture specifications, and ceremonial protocols—into a single reference that carpenters passed down through apprenticeship lines.

What makes it remarkable is not just the technical content. It is the insistence that building well requires more than skill. It requires timing, orientation, awareness of the natural order, and a deep respect for materials. A carpenter consulting the Lu Ban Jing was not simply building a house. He was negotiating with forces—structural, spiritual, and practical—that demanded equal attention.

For anyone who has tried to understand why traditional wooden puzzles feel so different from modern plastic gadgets, this manual offers a clue. The wood was never just material. It was a partner.

Measurements That Meant More Than Numbers

The first thing that strikes a modern reader about the Lu Ban Jing is its obsession with exact dimensions. Every component of a building—the height of a hall, the width of a doorway, the depth of a corridor, the spacing between columns—is prescribed down to the fen, a unit roughly equivalent to a third of a centimeter.

A main hall, records describe, should stand with its central columns a specific number of chi tall, its side corridors proportioned at precise ratios. Water channels flanking the entrance follow their own dimensional rules. The front gate must be wide enough to convey dignity but not so wide that it dissipates energy. Even the number of lotus-leaf carvings on a bracket is stipulated.

But these are not arbitrary numbers. Traditional Chinese builders worked with a system called the Lu Ban Chi—a specialized ruler divided into eight sections, each assigned a meaning: wealth, illness, separation, righteousness, office, calamity, harm, and fortune. A doorway measuring within the “wealth” segment was considered auspicious. One falling in “illness” was not.

This sounds like superstition, and in one sense it is. But there is a subtler logic at work. The Lu Ban Chi forced builders to standardize proportions. By restricting acceptable dimensions to specific ranges, the system ensured that doors, windows, and rooms fell within ratios that happened to be structurally sound and visually balanced. The mystical framework served as a constraint system—a set of rules that guided builders toward good design without requiring them to understand the underlying geometry.

Modern designers call this “guardrails.” The Lu Ban Jing called it fate.

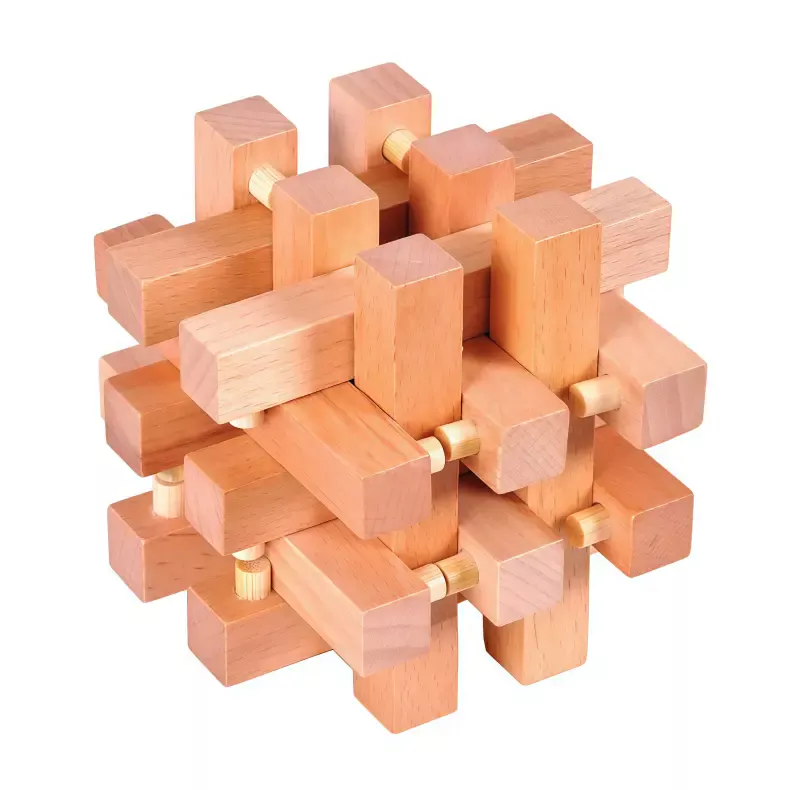

Joints That Hold Without Nails

The structural heart of the Lu Ban Jing is mortise-and-tenon joinery. Every major connection in traditional Chinese architecture—beam to column, bracket to eave, rail to post—relies on interlocking wood shapes rather than metal fasteners.

The manual describes dozens of joint types with exacting specifications. A tenon for a load-bearing beam might be prescribed at a specific width and depth, with tolerances tight enough that the assembled joint resists both compression and lateral shear. The key insight is that wood moves. It expands and contracts with humidity, shifts under load, and ages unevenly. A nail fights these forces. A well-cut joint accommodates them.

This principle—designing for movement rather than against it—is what makes traditional joinery so resilient. The Forbidden City in Beijing, built using methods consistent with the Lu Ban Jing, has survived more than two hundred recorded earthquakes over six centuries. Its wooden frame flexes where a rigid structure would crack.

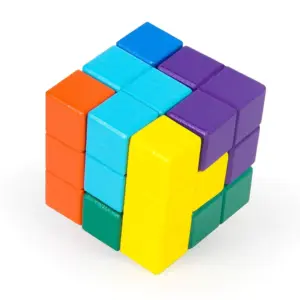

The same principle animates the interlocking puzzles that evolved directly from this joinery tradition. Anyone who has wrestled with a wooden brain teaser puzzle guide knows the sensation: pieces that seem impossible to separate are held together only by geometry. No glue, no pins, just the precise fit of wood against wood.

Luban Lock Set – 9 Piece

This is the most direct descendant of the Lu Ban Jing’s joinery principles available as a hands-on object. The set contains nine separate interlocking puzzles, each built on mortise-and-tenon logic. You disassemble them first—which feels easy—and then discover that reassembly is the real test. Difficulty ranges from the approachable Six-Way Cross to the Luban Ball, which has humbled more than a few confident engineers. Skip this if you want quick wins; the harder pieces in this set demand genuine spatial patience.

- 9 distinct interlocking puzzles

- Natural wood construction, no adhesives

- Difficulty range: beginner to advanced

- Price: $39.99

View the Luban Lock Set – 9 Piece →

12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set

Here is the same joinery logic made visible. These twelve mini Luban locks are cast in transparent acrylic, so you can see every notch and groove from the outside. Seeing the mechanism, however, does not mean solving it—a lesson the Lu Ban Jing would endorse. Each piece measures just 3.7 to 5.5 centimeters, making the set portable and desk-friendly. Not ideal if you prefer the tactile warmth of real wood, but perfect for understanding how interlocking geometry works at a glance.

- 12 transparent acrylic Luban locks

- Compact size for desk or travel

- Visual learning advantage

- Price: $28.88

View the 12 Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set →

When the Building Tells You When to Build

The Lu Ban Jing does not stop at measurements and joints. A substantial portion of the text is devoted to calendrical rules—prescriptions about when construction should begin, which days are auspicious for specific tasks, and which months to avoid entirely.

Records describe a system tied to the Chinese lunar calendar, with each month assigned specific heavenly stems and earthly branches. Certain days were designated for raising beams. Others were forbidden for setting foundations. The logic wove together astronomical observations, seasonal patterns, and a cosmological framework that treated the building site as a living intersection of time and space.

To modern eyes, this looks like the part to skip. But consider what it actually accomplished. By restricting construction to specific windows, the system prevented builders from starting projects during monsoon season, extreme cold, or harvest time when labor was scarce. The calendar rules also created natural pauses—rest periods built into the workflow—that reduced errors caused by fatigue or haste.

One old line from the tradition puts it this way: the carpenter who rushes to raise a beam on the wrong day will spend a lifetime repairing the mistake. Whether you read that as spiritual counsel or project management advice, the practical effect is identical.

If you enjoy the idea of testing your own sense of timing and balance, the yin-yang balance puzzle game offers a surprisingly apt digital analogy—placing elements in the right positions until the whole system reaches equilibrium.

Materials, Orientation, and the Art of Paying Attention

The Lu Ban Jing is particular about materials. Not all wood is equal. Craftsmen learned early that timber selection depended on the intended use: load-bearing columns demanded dense, straight-grained hardwoods, while decorative elements could use softer, more easily carved species. The text advises examining the grain direction, checking for hidden knots, and understanding how each species responds to the region’s climate.

Orientation matters equally. Buildings in the Lu Ban tradition face south to capture winter sunlight and deflect northern winds—a practice grounded in both feng shui philosophy and basic thermal logic. The manual specifies how the main hall should relate to its corridors, gates, and courtyards, creating a spatial sequence that controls airflow, light, and the psychological experience of moving through a structure.

This attention to orientation extends to smaller objects. The mechanical puzzle collection guide on Tea Sip touches on a similar idea: the way you approach a puzzle—literally the angle from which you first examine it—often determines whether you solve it in minutes or hours. Orientation is not decoration. It is strategy.

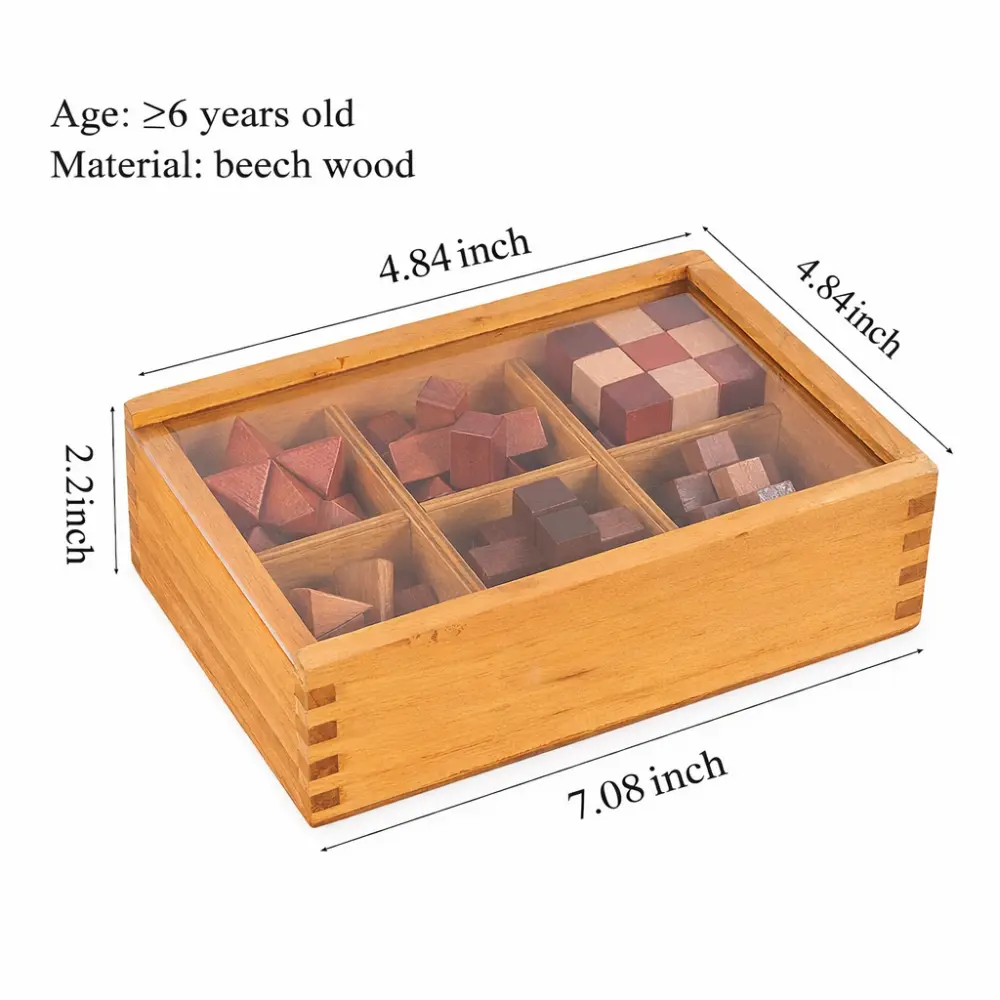

6-in-1 Wooden Brain Teaser Set

Six different interlocking puzzles in one box, each demanding a distinct approach to disassembly and reassembly. This set embodies the Lu Ban Jing’s principle that mastering one joint does not prepare you for the next. Each puzzle uses a different locking mechanism, forcing you to abandon what worked before and think fresh. Good for building a breadth of spatial skills. Less useful if you want depth on a single challenge type.

- 6 distinct wooden interlocking puzzles

- Natural wood construction

- Ranges from beginner to intermediate

- Price: $38.88

View the 6-in-1 Wooden Brain Teaser Set →

The 6 Piece Wooden Puzzle Key operates on a related principle—a single object whose six components must be understood individually before the whole makes sense. It is a miniature lesson in the kind of part-to-whole thinking the Lu Ban Jing demanded from every apprentice.

Taboos, Warnings, and the Honesty of Constraints

Perhaps the most surprising sections of the Lu Ban Jing are its taboos. The text forbids specific actions during construction: do not cut timber on certain days, do not position a beam in certain directions, do not allow certain activities on the building site. Some prohibitions seem purely ritualistic. Others contain embedded safety logic.

The injunction against eating certain foods on the construction site, for instance, may have served a hygienic purpose in an era before refrigeration. The warnings against building during specific weather conditions prevented workers from handling heavy timber on wet, slippery ground. Even the prohibition against certain verbal expressions on-site—a superstition about unlucky words—effectively enforced a culture of focus and seriousness in a dangerous working environment.

Constraints, it turns out, are not the enemy of creativity. They are its scaffold. The Lu Ban Jing understood that a carpenter freed from all rules is a carpenter who makes expensive mistakes. Every prohibition was a lesson someone paid for with a collapsed beam or a ruined season of timber.

This is the same reason puzzle designers build in limitations. A puzzle with infinite moves is not challenging—it is boring. A puzzle with tight constraints forces invention within boundaries, which is where the satisfaction lives. The blog post on puzzle design through the lens of mechanical engineering explores this idea in detail: every good puzzle is a set of rules that makes one specific solution feel like a discovery.

Bridges, Pavilions, and Things That Must Be Beautiful to Work

The Lu Ban Jing does not treat function and beauty as separate concerns. Bridge specifications include not just load calculations but aesthetic prescriptions—the curve of an arch, the proportion of railings to span, the visual weight of end posts. Pavilion designs balance structural requirements with the experience of sitting inside them: how much sky is visible, how wind moves through the open sides, how the roof line frames the surrounding landscape.

This integration of the functional and the beautiful is the Lu Ban Jing’s most transferable idea. A well-made object should work properly. But it should also reward attention. The grain of the wood, the precision of the fit, the proportion of one part to another—these are not extras. They are the reason someone keeps an object instead of discarding it.

The Galleon Ship 3D Wooden Puzzle Model Kit captures this dual quality. Building it requires following structural logic—hull ribs, mast connections, deck layers—but the finished object is genuinely handsome. It functions as both a construction challenge and a display piece, which is exactly what the Lu Ban tradition demanded of every built thing.

Similarly, the 3D Wooden Puzzle Treasure Box merges mechanical joinery with a practical purpose. The box locks and unlocks through interlocking wooden mechanisms—no metal hardware—and stores small items once opened. Craft and function, fused into one object.

Who Should Skip This Entirely

Not everyone needs the Lu Ban Jing’s worldview, and not everyone will enjoy the objects it inspired. If you want puzzles that can be solved in under a minute, interlocking wooden sets will frustrate you. If you prefer digital entertainment to physical manipulation, a wooden Luban lock will collect dust. If the idea of spending twenty minutes rotating a six-piece assembly with no instruction manual sounds like punishment rather than recreation, this tradition is not for you.

There is also a personality mismatch to consider. The Lu Ban Jing rewards patience, repetition, and comfort with ambiguity. If your approach to problems is to brute-force solutions quickly, these puzzles—and this philosophy—will feel needlessly slow. That is not a flaw in the tradition. It is a feature, designed for people who find satisfaction in the process rather than the result.

For those who do enjoy that kind of slow, tactile problem-solving, the blog post on when a puzzle becomes a practice articulates it well: there is a difference between solving something and understanding it.

The Modern Workshop: Carrying Forward What Still Works

The Lu Ban Jing was written for professional builders constructing halls, temples, and bridges. Its direct applicability to modern life is limited—nobody is consulting a Ming dynasty manual to frame their garage. But the principles embedded in it are surprisingly portable.

The idea that constraints improve outcomes applies to everything from writing to software design. The discipline of checking orientation before committing to a plan is just good practice. The understanding that materials have their own logic—and that fighting that logic produces worse results than collaborating with it—is as relevant to woodworking today as it was six hundred years ago.

And the Lu Ban Jing’s central conviction—that a builder’s education is never complete, that there is always a finer joint to learn, a subtler proportion to master—is the reason interlocking puzzles continue to captivate people who have access to every form of digital entertainment imaginable.

The Chinese Old Style Fu Lock with Key is a tangible example. This brass padlock uses a traditional Chinese locking mechanism—the kind referenced in historical craft texts—that requires understanding rather than force to operate. It connects a modern user to the exact lineage of precision metalwork that ran parallel to the carpentry tradition.

The Chinese Koi Puzzle Lock pushes further into the decorative-functional overlap. Shaped like a carp—a symbol of persistence and transformation in Chinese culture—it is a working lock that also requires puzzle-solving to open. The form carries meaning. The mechanism carries function. Neither is optional.

3D Wooden Puzzle Safe

This is where the Lu Ban Jing’s principle of joinery meets modern ingenuity. The safe assembles from wooden pieces into a functional box with a working combination lock—no metal fasteners in the structural body. It is a legitimate storage object built entirely from interlocking wood. The assembly process teaches you exactly how the locking mechanism works, which means you understand the object at a level most people never reach with mass-produced safes. Skip this if you need actual security; it is clever woodcraft, not a bank vault.

- Wooden construction with combination lock mechanism

- Assembles from flat pieces into a 3D functional object

- Educational and decorative

View the 3D Wooden Puzzle Safe →

For those who want a broader survey of puzzle locks and their mechanisms, the puzzle locks topic guide covers the full spectrum from simple trick locks to multi-step sequential designs.

What the Old Builders Knew That We Keep Forgetting

There is a passage in traditional carpentry lore—echoed across multiple historical workshop texts—that advises a builder to study a site for a full day before making a single mark. Watch where the light falls in the morning. Note where water collects after rain. Observe which direction the wind enters. Only then, with a full cycle of observation complete, should you pick up your tools.

Modern productivity culture would call this wasted time. The Lu Ban Jing would call it the only time that matters.

This is not mysticism. It is the recognition that understanding precedes action, and that rushing past the understanding phase creates problems that no amount of skill can fix later. It is the reason a memory match game rewards observation over speed—the player who studies the board before flipping cards outperforms the one who starts clicking immediately.

The Three Brothers Lock Puzzle ($11.99) distills this insight into a palm-sized metal object. Three interlocking pieces that look identical but behave differently. Pulling harder does not help. Only careful observation of how each piece relates to the others reveals the separation sequence.

The 18 Piece Wooden Puzzle extends the same idea to a larger scale—eighteen wooden components that form a single sphere when correctly assembled. The instructions are absent by design. You must observe, test, and learn from failure, which is the Lu Ban Jing’s entire pedagogical method compressed into a single object.

The Wooden Desk Organizer with Perpetual Calendar sits at the intersection of function and craft in a way the old master builders would have recognized. It is a working desk tool—pen holder, calendar, organizer—built from interlocking wooden pieces. You assemble it yourself. You understand how it works. And then you use it every day, which is the highest compliment the Lu Ban tradition can pay to any built object.

For a broader look at how the Lu Ban legacy shaped not just construction but the puzzle traditions that followed, the blog post tracing the ancient carpentry text behind modern puzzles provides additional context worth reading alongside this piece.

Build Slow, Build Once

The Lu Ban Jing has survived for six centuries not because its specific measurements still apply—they do not—but because its underlying logic does. Build with the grain, not against it. Measure before cutting. Respect the materials. Accept that some knowledge only comes through handling, not reading. And understand that a joint made with patience will outlast one made with force by generations.

Those principles do not require a construction site. They apply every time you pick up an interlocking puzzle and rotate the first piece, looking for the angle that will make everything else fall into place. The old builders would recognize what you are doing. They wrote a manual for it.