A teacher forced his students to memorize lines they didn’t understand. Decades passed. One of those students — now older, wiser, more bruised by life — picked up a set of tiles, arranged symbols on them, shuffled them around like a card game, and suddenly understood what the words meant. Not because he studied harder. Because he played.

That story comes from a tradition thousands of years old. A scholar once insisted that the only way to grasp a complex system of patterns — eight fundamental symbols representing everything from sky to earth, fire to water — was to stop treating it as a textbook and start treating it as a game. Carve the symbols onto tiles. Shuffle them. Arrange and rearrange. Let your hands teach your brain.

He called this principle something that translates roughly to “play and explore, and understanding follows.” It’s the oldest argument for hands-on learning ever recorded. And it turns out to be the single most useful piece of advice for anyone staring at a metal brain teaser that refuses to come apart.

The Trouble With Studying Something You Can’t See

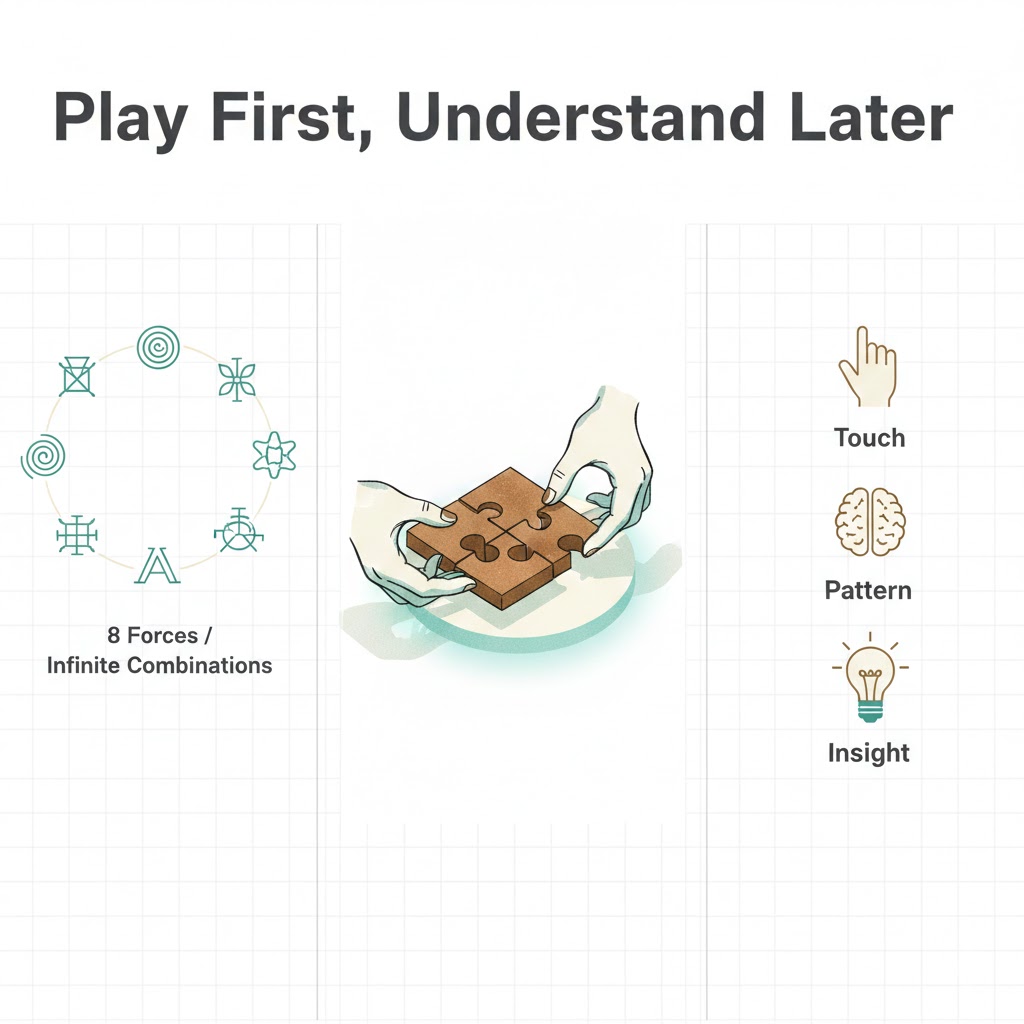

Here’s the problem the old scholars faced. They had a system — eight symbols, each built from combinations of broken and unbroken lines — that described the fundamental forces of the natural world. Heaven and earth. Sun and moon. Thunder and wind. Mountain and water. Eight phenomena, arranged in pairs of opposites, generating infinite combinations.

Sounds abstract. It was abstract. For centuries, teachers made students memorize the sequences. Recite the order. Know which symbol sat opposite which. Students could pass tests without ever grasping why any of it mattered.

One particularly honest scholar admitted he suffered through this exact education. His teachers demanded memorization. When he asked what the patterns actually meant, the teachers couldn’t explain — probably because they didn’t know either. They recognized the characters on the page without understanding the system behind them.

It wasn’t until years later, when he began physically manipulating the symbols — first using chess-like pieces on a board, then switching to tile sets he could shuffle and rearrange — that the relationships clicked. The abstract became concrete. The memorized became understood.

This is not a metaphor. This is literally what happens when you pick up a six-piece wooden brain teaser set for the first time. You can read the instructions. You can watch a video. None of it matters until your fingers start moving pieces, testing orientations, feeling where wood catches on wood. The understanding lives in the doing.

Eight Symbols, Eight Natural Forces

The system those scholars were wrestling with organized the entire observable universe into eight categories. Not nine, not seven — exactly eight, each one paired with its opposite.

The first pair: heaven and earth. One represents everything above. The other, everything below your feet. Simple enough — until you realize these aren’t just labels. They’re principles. Heaven implies creative force, expansion, initiative. Earth implies receptive force, support, responsiveness.

The second pair: sun and moon. Or more precisely, fire and water. Two forces spinning endlessly between heaven and earth. The scholars noticed these opposites don’t just coexist — they generate motion. Fire rises. Water falls. Their interaction drives change.

Then thunder and wind. Energy in motion. One is sudden, violent, a shock that initiates. The other is persistent, pervasive, a force that follows through. An old phrase captures it: “thunder and wind chase each other.” The shock creates the movement; the wind carries it forward.

Finally, mountain and water — or more precisely, stillness and flow. The mountain stands. The river moves. Stability and change, existing side by side.

Eight forces. Four pairs of opposites. And here’s what made the scholars’ heads spin: these eight, combined with each other, produced sixty-four configurations. Those sixty-four could describe any situation, any dynamic, any pattern in the natural world. The system was finite in its parts but infinite in its applications.

If that sounds like a combinatorial puzzle, it’s because it is one. The twelve-piece crystal interlocking set operates on a similar principle — a limited number of pieces producing a staggering number of possible arrangements, with only a few that actually work.

Why Playing Beats Studying

The scholar who championed the play-first approach wasn’t being lazy. He was making a cognitive argument centuries ahead of its time.

His point was this: when you treat a complex system as something to memorize, you engage only your verbal and sequential memory. You can recite the eight symbols in order. Congratulations — you’ve learned a list. You haven’t learned a system.

But when you put those symbols on tiles and start arranging them spatially — placing opposites across from each other, testing what happens when you swap positions, noticing which combinations feel “balanced” and which feel “tense” — you engage spatial reasoning, pattern recognition, and kinesthetic memory all at once. The system doesn’t just live in your head anymore. It lives in your hands.

Modern cognitive science backs this up. Researchers at the University of Chicago have documented how physical manipulation of objects enhances abstract reasoning, particularly for relational concepts. When you rotate a puzzle piece in your fingers, you’re not just testing a physical fit — you’re modeling a spatial relationship that would take much longer to process purely mentally.

The scholar even had a dream for the future: he wished someone would create an interactive device — like a planetarium instrument, he said — where you could explore the system playfully, seeing the patterns shift and recombine in real time. He was describing, in essence, a puzzle toy. In the era before electricity.

This is why a traditional mechanical puzzle lock teaches patience more effectively than any lecture about patience. Your hands learn what your mind can only theorize about. You feel the mechanism resist. You feel the moment it gives way. That tactile feedback encodes the lesson deeper than any text.

Two Maps of the Same Territory

The ancient system had two different arrangements of the eight symbols — and the difference between them reveals something important about how puzzles work.

The first arrangement, attributed to a mythical sage, placed the symbols according to pure opposition. Heaven at the top, earth at the bottom. Fire on the left, water on the right. Perfect symmetry. Perfect balance. This was the idealized map — how the forces relate in theory.

The second arrangement, created by a later historical king, shuffled the positions entirely. Fire moved to the top. Water dropped to the bottom. The opposites no longer faced each other directly. This map wasn’t about ideal structure — it was about practical reality. How do these forces actually behave in the world? Where does energy actually flow?

Two maps. Same eight pieces. Completely different configurations. And the scholars argued about which one was “correct” for over a thousand years.

If you’ve ever held a cast galaxy metal puzzle in your hands — four silver pieces that interlock in multiple orientations — you know this experience intimately. The pieces fit together one way to form a compact shape. They fit together another way to form something looser, more open. Neither configuration is wrong. They’re different solutions to the same set of constraints.

Understanding this distinction — that the same elements can be validly arranged in multiple ways depending on your purpose — is one of the most transferable skills puzzle-solving develops. It’s why seasoned solvers approach new challenges differently than beginners. Beginners look for the answer. Experienced solvers look for the system.

The Principle of Opposing Pairs

Let’s stay with the idea of opposition for a moment, because it runs deeper than you might expect.

The old texts describe how the eight forces pair off: heaven and earth “define position.” Mountain and lake “exchange energy.” Thunder and wind “chase each other.” Fire and water “don’t shoot at each other” — meaning they maintain their distinct natures even while interacting. Each pair creates a specific dynamic. None of the opposites are enemies. They’re dance partners.

This is not a poetic abstraction. It’s a structural principle that appears in nearly every well-designed mechanical puzzle.

Take a metal interlocking disk puzzle. Two pieces, made from the same material, shaped to grip each other. They resist separation not through force but through geometry — each piece’s shape is the other’s constraint. Remove the constraint, and both pieces are just flat metal. It’s the opposition that creates the puzzle. It’s the opposition that creates the value.

The yin-yang logic game explores this same idea digitally, if you want to feel how opposing forces create structure without any physical pieces in your hands.

The scholars who studied these patterns noticed that the eight forces, despite being “only” eight, produced effectively infinite variation when combined. A mountain touching water created one meaning. A mountain touching fire created another. The same element, in a different pairing, produced a different result. They documented sixty-four primary combinations and noted that even those were just the surface — “the transformations are inexhaustible.”

This is the mathematics of interlocking puzzles in a nutshell. A modest number of pieces. A rule set governing how they interact. And an outcome space far larger than you’d expect from counting parts.

Hands-On Pattern Recognition Is a Trainable Skill

Here is where the ancient insight meets modern neuroscience in a way that actually matters for your puzzle shelf.

The scholar’s method — carving symbols on tiles and shuffling them daily — was a deliberate practice routine. Not study. Not review. Practice. The same distinction athletes and musicians understand: reading about a technique is not the same as performing it repeatedly until your body knows the movement.

When you sit with a traditional Jiutong lock and spend twenty minutes testing orientations, you’re training exactly the pattern-recognition circuits that the old scholars were exercising with their tile-shuffling sessions. You’re building what psychologists call “perceptual fluency” — the ability to rapidly identify meaningful patterns in complex visual-spatial information.

This isn’t feel-good speculation. A 2019 study in the journal Acta Psychologica documented measurable improvements in spatial reasoning after participants engaged in regular mechanical puzzle manipulation, with effects persisting weeks after the practice ended. The scholars didn’t have brain scanners, but they had thousands of years of observational evidence pointing to the same conclusion.

The key insight: you don’t need to understand why a puzzle works to benefit from working it. Understanding comes after the doing, not before. Play first. Comprehend later. This is literally what the old phrase means.

Luban Lock Set — 9-Piece Collection

The Luban Lock Set takes this principle and gives it physical form. Nine interlocking wooden puzzles, each requiring you to discover a hidden sequence of moves through trial and observation. You cannot solve these by reading instructions — or rather, you can, but you’ll miss the entire point. The point is the search. The point is training your hands to think. Difficulty ranges from accessible to genuinely challenging, making this set one of the best investments for anyone who wants to build spatial reasoning systematically rather than randomly. Start with the simplest lock. Notice the patterns. Apply what you’ve learned to the next one. This is the tile-shuffling method, updated for a modern desk.

Cast Hook Metal Brain Teaser

The Cast Hook puzzle demonstrates what the scholars meant by “opposing forces that don’t conflict.” Two interlocked metal hooks, each one’s curve creating the other’s constraint. The separation move isn’t about force — it’s about finding the exact angle where opposition becomes freedom. Most people try brute strength first. Most people are wrong. The hooks teach a specific lesson: when two forces are locked together, the solution is almost never more force. It’s a change of angle. The old texts had a phrase for this too — the idea that opposing elements “exchange energy” rather than destroy each other. The Hook makes that principle tangible.

Who Should Skip This Entire Way of Thinking

Not everyone finds value in the play-first-understand-later approach, and that’s worth acknowledging honestly.

If you need immediate results and measurable outcomes from every activity, puzzle-based pattern training will frustrate you. The insights arrive on their own schedule. Some people sit with a barrel-shaped Luban lock for an evening and feel the click of understanding. Others need weeks. The process cannot be rushed, and that’s the point — but it’s also a genuine limitation.

If you strongly prefer digital, screen-based learning, physical puzzles may feel unnecessarily slow. The haptic element is what makes them work, cognitively speaking, but if holding a wooden object feels like a step backward from your usual workflow, the benefit diminishes.

And if you’re looking for competitive puzzle-solving — speed records, tournament preparation, optimized solutions — the contemplative tradition described here is the wrong framework entirely. Speed-solving and play-based exploration serve different goals. Neither is superior. They’re just different configurations of the same elements, like those two ancient maps.

From Pattern to Practice: Applying the Principle Daily

The old scholars weren’t content with understanding patterns intellectually. They wanted to use them. The eight-symbol system wasn’t just a cosmological map — it was a decision-making tool. Facing a choice? Consider which forces are in play. Notice where opposition exists. Find the configuration that allows all elements to interact without destruction.

This translates more directly to modern life than you’d expect. The principle of opposing pairs — that constraints create structure, not just limitation — applies to everything from project management to relationship dynamics. The principle that the same elements produce different outcomes depending on arrangement is essentially the core of strategic thinking.

You don’t need to study any ancient text to absorb these lessons. You just need to spend time with objects that embody them. A bronze keyring puzzle in your pocket provides dozens of micro-sessions per day — waiting for coffee, riding the subway, sitting through a meeting that could have been an email. Each session is a few seconds of spatial reasoning practice. Over weeks and months, those seconds compound.

The five-piece spiral metal puzzle is another strong daily carry option. Five pieces that interlock in a spiral configuration, requiring you to find the exact rotational sequence for separation. The spiral form itself echoes one of the oldest symbolic representations of natural cycles — energy moving outward and returning, endlessly.

If you’re drawn to the deeper history behind why physical puzzles work the way they do, the story of the carpenter who wrote the rules that governed Chinese puzzle design for centuries is worth your time. That tradition’s core belief — that a good joint teaches geometry better than any diagram — comes from the exact same philosophical root.

The Diagram That Changed Everything (And Almost Didn’t Exist)

One detail from the historical record deserves mention because it reveals something about how knowledge systems evolve.

The circular diagram that most people associate with the eight-symbol system — the one you’ve probably seen on flags, martial arts logos, and philosophy book covers — didn’t actually exist until relatively late in the tradition’s history. Before a certain dynasty, scholars studied the system purely through text. No visual diagram. No spatial map. Just words describing relationships between abstract concepts.

When the diagram finally appeared, it transformed understanding overnight. Suddenly, the spatial relationships between opposing forces were visible. You could see that heaven and earth were at opposite poles. You could trace the cycle of thunder-wind-fire-water around the circle. The system that had seemed impossibly abstract became intuitive — because it became visual and spatial.

This is the same leap that happens when someone moves from reading about a wooden brain teaser to actually holding one. Description collapses into experience. Abstract geometry becomes tangible feedback. And understanding, which had been hovering just out of reach, suddenly lands.

The scholars who explored the ancient carpentry traditions behind modern puzzles understood this transformation implicitly. Their entire craft was built on the premise that physical objects teach what words cannot.

What “Infinite Combinations From Finite Parts” Actually Means for Your Desk

Let’s bring this back to something concrete.

The eight symbols produce sixty-four combinations. Those sixty-four each have six internal positions that can change, creating 4,096 sub-states. The old scholars noted that this already exceeds what any single human could memorize — and that was the point. The system was designed not to be memorized but to be navigated. You learn the eight base elements. You learn the rules of combination. Then you explore.

A well-curated puzzle shelf works the same way. You don’t need a hundred puzzles. You need eight to twelve that operate on different principles — interlocking, sequential, disentanglement, rotational — and you need the patience to explore each one thoroughly.

3D Wooden Perpetual Calendar Puzzle

The Perpetual Calendar puzzle embodies the cycle principle directly. It’s a functional calendar built from interlocking wooden components, requiring assembly that mirrors how cyclical time actually works — days within months within years, each unit fitting inside the next. The finished object sits on your desk as both a tool and a reminder: systems are made of repeating, nested patterns. Once you grasp the pattern at one level, it repeats at every level.

Gold Fish & Silver Coral Reef Cast Puzzle

The Gold Fish and Silver Coral Reef puzzle is opposition made physical. Two cast metal pieces — one gold-toned, one silver — locked together in a configuration that requires precise rotational movement to separate. The color contrast isn’t just aesthetic. It’s a visual representation of two distinct forces, intertwined, neither dominating, each one defining the other’s boundary. If you want to feel what “opposing forces exchange energy” means without reading a single philosophical text, hold this puzzle for ten minutes.

The Memory Game Connection

The old scholars had a specific method for developing pattern fluency. They’d lay out tiles representing the eight symbols, study them briefly, then flip them face-down and try to recall positions. This is, recognizably, a memory matching game — the same mechanic used in modern cognitive training apps and, more relevantly, in the memory match game available as a free brain exercise.

The connection isn’t coincidental. Pattern recognition, spatial memory, and the ability to hold multiple elements in working memory simultaneously are all trainable skills that transfer across domains. The scholars knew this empirically. Modern research confirms it experimentally.

What the scholars added — and what most modern brain-training programs miss — is the philosophical dimension. They weren’t just exercising cognition. They were cultivating a specific orientation toward complexity: approach it playfully, explore it systematically, and trust that understanding will arrive in its own time.

This is why the relationship between puzzle design and engineering principles runs so deep. Both disciplines share the conviction that complex systems become manageable when you break them into interacting pairs of opposing forces.

A System for Starting

If you’re drawn to this play-first philosophy and want to build a physical practice around it, here’s a framework based on the ancient system’s own structure:

Start with one pair of opposites. Pick any two-piece metal puzzle — the interlocking disks, the cast hooks, the seahorse pair. Spend a week with it. Don’t research solutions. Just play. Notice when you’re forcing. Notice when the pieces want to move.

Then add complexity. Move to a multi-piece puzzle like the Luban Lock set. Now you’re managing not just one pair but several interlocking relationships simultaneously. The cognitive load increases. The pattern-recognition muscles get a real workout.

Then add reflection. After solving (or failing to solve), sit with the question: what principle was this puzzle teaching? Stability? Flexibility? Sequence? Opposition? The scholars believed that naming the principle after experiencing it was far more valuable than learning the name first.

This sequence mirrors the original system’s progression: from two symbols (heaven and earth) to four pairs to sixty-four combinations. Start simple. Build deliberately. Let complexity emerge from mastered fundamentals.

The collection of locking brain teasers is a practical starting point if you want curated options for each stage.

What Understanding Feels Like

The scholar who wrote about his tile-shuffling breakthrough described the moment of understanding not as a flash of insight but as a gradual settling. Things that had been separate began connecting. Patterns that had seemed arbitrary revealed their logic. The system didn’t change — his relationship to it changed. Because he’d spent enough time playing with the parts, the whole finally made sense.

Anyone who’s solved a difficult puzzle recognizes this feeling. It’s not the “aha!” moment of getting the answer. It’s the slower, deeper realization that you now see the logic that was always there. The puzzle didn’t get easier. You got better at seeing.

That’s what “play and explore, and understanding follows” actually promises. Not quick answers. Not guaranteed success. Just this: if you engage with complex systems through your hands, with patience and without forcing, understanding arrives. It arrives on its own schedule. It arrives more deeply than memorization could ever deliver. And it stays.

The question was never whether the old scholars were right about play being the path to understanding. Every child who’s ever built a tower of blocks and watched it fall already knew the answer.

The question is whether you’re willing to pick up the pieces and start.