You are holding something small in your hand — a metal puzzle, maybe, or a wooden lock that refuses to open. You twist it. Nothing happens. You flip it. Still nothing. You stare at it, and a quiet frustration builds behind your eyes.

Then something shifts. Not in the puzzle. In you.

You notice a groove you missed. A piece that wobbles differently from the rest. A shape that doesn’t quite match the others. And suddenly, without fully understanding why, your fingers do the right thing. The mechanism clicks. The lock opens.

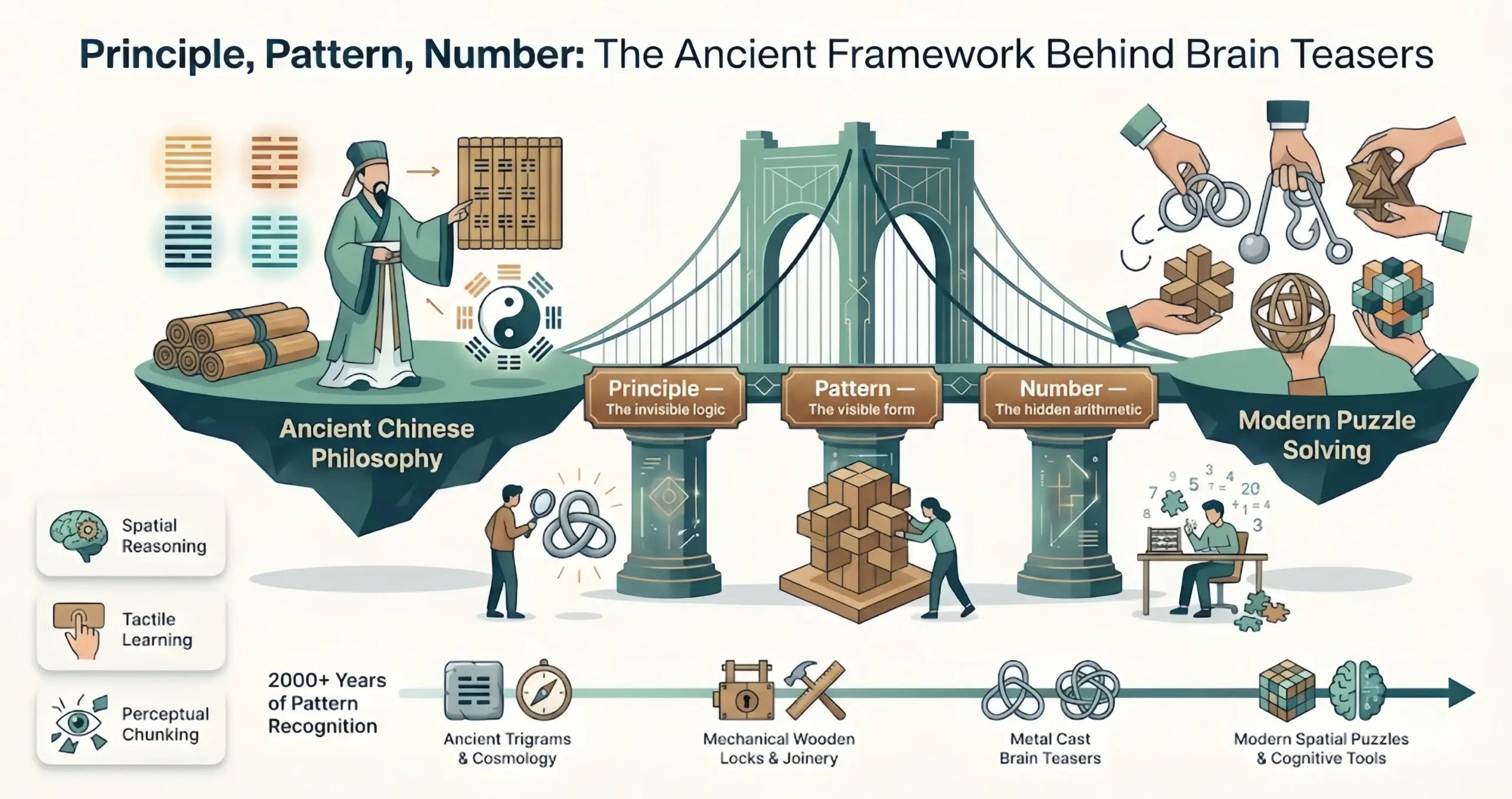

What just happened in your brain isn’t random. It follows a framework that scholars mapped out over two thousand years ago — a way of understanding how everything in the universe operates through three interlocking layers: the reason something exists, the form it takes, and the numbers that govern its behavior.

This isn’t mysticism. It’s a practical model for thinking clearly. And it explains, with surprising precision, why puzzles train your mind better than almost anything else you can do with your hands.

The Three Dimensions of Everything

Traditional Chinese philosophy recognized that every phenomenon — from the orbit of planets to the sway of a teacup lifted from a table — operates on three simultaneous levels.

The first is principle — the underlying reason a thing works the way it does. Not just the mechanical explanation, but the deeper logic. Why does a lock resist opening? Because concealment requires effort to undo. Why does a puzzle have a solution at all? Because every constraint implies a path through it.

The second is pattern — the visible form, the shape, the appearance. The curve of interlocking metal. The grain direction of wooden pieces. The way light catches a crystal surface differently depending on how the facets are arranged. Pattern is what you see before you understand.

The third is number — the measurable dimension. How many pieces. How many moves to solve. The angle of rotation required. The precise tolerance between two components that allows one to slide past the other. Number is the hidden arithmetic of physical reality.

Old records describe how someone deeply versed in these three layers could examine any object or situation and understand it completely — not through magic, but through disciplined observation. Pick up a cup from a table and watch it sway: the swaying is the pattern, the frequency and arc are the number, and the reason it sways at all — gravity acting on mass displaced from equilibrium — is the principle.

Every puzzle you have ever solved, or failed to solve, operates on exactly these three layers. And the reason puzzles are genuinely good for your brain is that they force you to engage all three simultaneously.

Why Your Brain Needs All Three Layers at Once

Modern cognitive science backs this up, though it uses different vocabulary. Researchers at institutions studying spatial reasoning have found that puzzle-solving activates multiple neural pathways simultaneously — visual processing (pattern), logical reasoning (principle), and quantitative estimation (number). The combination is rare in everyday life. Most tasks only require one or two of these systems at once.

When you scroll through a phone, you’re doing almost no spatial reasoning. When you read a book, you’re processing language but not manipulating physical forms. When you do arithmetic, the numbers are abstract, disconnected from anything you can hold.

Puzzles collapse all three into a single experience. You hold the pattern. You feel the number (the weight, the resistance, the click at exactly the right angle). And you discover the principle through your fingertips, not through explanation.

One old line puts it this way: once you truly understand the reason, the form, and the measure of a thing, you can know its changes before they happen. That sounds grandiose until you watch someone experienced pick up a metal brain teaser and solve it in seconds. They aren’t faster because they’ve memorized the answer — they’re faster because they’ve internalized how principles, patterns, and numbers interact.

Principle: The Invisible Logic Inside Every Puzzle

The principle layer is the most important and the least visible. It’s the reason a mechanism does what it does.

Consider a cast metal puzzle — two pieces of zinc alloy interlocked so tightly they appear to be one solid object. The principle isn’t the shape of the pieces. The principle is that there exists exactly one orientation in three-dimensional space where the two pieces can pass through each other. Every other angle is blocked. The designer chose that angle, embedded it in metal, and handed you the job of finding it.

This is why brute force rarely works on well-designed puzzles. Forcing a puzzle is like trying to argue with physics. The principle doesn’t care about your effort — it only responds to the correct approach.

Tradition holds that craftsmen who understood underlying principles could design objects that seemed impossible. A wooden lock with no visible keyhole. A metal ring that passes through a solid bar. A box with no seams that somehow opens. The craft wasn’t deception — it was deep understanding of how materials and geometry interact, expressed in physical form.

Cast Galaxy 4-Piece Silver

This metal brain teaser separates into four distinct silver-toned pieces, each curved in a way that suggests astronomical orbits. The principle at work is rotational symmetry — the pieces only separate when rotated along axes that mirror their design curves. It rewards the kind of thinking where you stop pulling and start turning, which is harder for your instincts than it sounds. The finish is smooth enough that you can feel the slight resistance change when you’ve found the right angle. Not ideal if you prefer puzzles with clear visual cues — the uniform silver color means you’re working entirely by feel and spatial reasoning.

View the Cast Galaxy 4-Piece Silver →

Interlocking Metal Disk Puzzle

Two flat metal disks appear fused together. The principle here is planar constraint — the solution requires finding a specific path within a two-dimensional plane rather than the three-dimensional space your brain assumes. Most solvers waste time trying to pull the disks apart vertically when the answer lies in a lateral slide. A compact exercise in questioning your own spatial assumptions.

View the Interlocking Metal Disk Puzzle →

The Antique Bronze Metal Keyring Puzzle operates on a similar idea — its vintage-looking rings conceal a pathway that only appears when you stop thinking about rings and start thinking about gaps.

Pattern: What You See Before You Understand

Pattern recognition is the second layer, and it’s the one most people associate with puzzle-solving. You look at an object and your brain starts sorting: symmetry, repetition, anomaly, alignment. These visual assessments happen fast — often faster than conscious thought.

But pattern recognition in puzzles goes deeper than “this piece looks like it fits there.” Experienced solvers develop what psychologists call perceptual chunking: the ability to see groups of features as single units rather than processing each detail individually. A chess grandmaster doesn’t see 32 pieces — they see formations. A puzzle enthusiast doesn’t see six wooden sticks — they see interlocking planes.

The ancient framework recognized this. Pattern, as a concept, wasn’t limited to appearance. It included behavior, tendency, and character. The pattern of a river isn’t just its shape on a map — it’s the way water moves within it. The pattern of a puzzle isn’t just its visual form — it’s the way its pieces want to move.

This is why wooden brain teasers are such effective trainers of perception. Wood has grain. Grain has direction. Direction affects how pieces slide, catch, and release. When you work a wooden puzzle, you’re reading pattern at multiple scales simultaneously — the macro shape of the assembly, the micro texture of each joint.

The Barrel Luban Lock

Named after Lu Ban, the legendary craftsman whose construction manuals influenced centuries of Chinese architecture, this barrel-shaped puzzle demands pure pattern reading. The pieces are cut so that their interlocking geometry only becomes visible once you’ve identified which face of the barrel is the entry point. The cylindrical form is deceptive — your brain expects symmetry to mean any face is equivalent, but the wood grain itself contains clues about orientation. A patient solver who looks before touching will solve it faster than an aggressive one who starts twisting immediately.

6-in-1 Wooden Brain Teaser Set

Six classic configurations in one set, each demanding a different pattern vocabulary. The value here is range — solving one puzzle teaches you a visual language that partially transfers to the next, but each has enough novelty to prevent rote memory from taking over. If you’re building pattern recognition as a skill rather than solving for a one-time dopamine hit, a graduated set is considerably more useful than a single showpiece.

View the 6-in-1 Wooden Brain Teaser Set →

Experienced collectors often note that after working through multiple wooden puzzles, they begin to notice structural patterns in everyday objects — the joinery in furniture, the way a cardboard box folds flat, how a door hinge distributes weight. For a more structured path through that learning curve, our guide to traditional wooden puzzles maps the progression from beginner to advanced geometries.

Number: The Hidden Arithmetic of Physical Things

The third layer is the one most people underestimate. Number isn’t just about counting. It’s about proportion, tolerance, and sequence.

Every mechanical puzzle has a numerical reality beneath its surface. The Tian Zi Grid Lock Puzzle, for instance, requires a specific sequence of moves — not just the right moves, but the right order. Skip a step and you’re locked out, not because the puzzle is punishing you, but because the mechanism has a mathematical structure that only permits one path.

Ancient thinkers observed that everything in the world has its number — the time it takes for a process to complete, the proportion between parts, the threshold at which something changes from one state to another. A tape being recorded has a measurable length, a measurable capacity, a measurable duration. Remove any of those numbers and the thing ceases to function.

In puzzle terms, number governs difficulty. A puzzle with three pieces and one solution pathway is categorically different from a puzzle with twelve pieces and forty-seven possible assemblies. The jump isn’t linear — it’s exponential. Each additional piece multiplies the complexity rather than merely adding to it.

Luban Lock Set — 9 Piece

Nine interlocking wooden pieces that form a single structure. The numerical complexity here is significant: the assembly sequence has over a dozen decision points, and a wrong choice at step three may not reveal itself as wrong until step seven, when the final piece refuses to seat. This is where number and patience intersect. The set teaches you to count your assumptions — literally, to track which choices you’ve made and which remain open. Solvers who keep mental (or physical) notes progress significantly faster. Not recommended as a first Luban lock — start with a 6-piece set to build your vocabulary first.

View the Luban Lock Set 9-Piece →

5-Piece Cast Spiral Metal Puzzle

Five spiral metal pieces wound together so tightly they resemble a single helix. The number to pay attention to here isn’t five — it’s the rotational angle between adjacent pieces. That angle is consistent, and discovering it is the key. Once you’ve identified the numerical relationship, the separation follows a predictable rhythm. This is a puzzle that rewards analytical persistence over trial-and-error guessing.

View the 5-Piece Cast Spiral Metal Puzzle →

The 12-Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set pushes the number dimension further — translucent pieces that let you see the internal structure, which counterintuitively makes the challenge harder because your brain receives more visual data than it can productively process.

The Danger of Mastering All Three

Here’s where the ancient framework takes an unexpected turn. The records include a warning: learn these three dimensions too well, and life becomes tedious.

The reasoning is counterintuitive but sound. If you can read the principle behind every situation, recognize every pattern before it fully forms, and calculate the number governing every outcome, then nothing surprises you anymore. You know what will happen before it happens. Anticipation replaces experience. Knowledge crowns out wonder.

The recommendation? Learn only half.

That sounds like false modesty, but there’s genuine wisdom in it — and genuine relevance for puzzle enthusiasts. The best solvers aren’t the ones who’ve memorized every mechanism. They’re the ones who maintain enough uncertainty to stay curious. They understand the principle well enough to narrow their approach, read patterns well enough to avoid obvious dead ends, and count well enough to track their progress — but they leave room for the puzzle to surprise them.

This is why physical puzzles outlast digital ones in long-term engagement. A digital puzzle, once solved, is fully exhausted — the algorithm is known, and there’s no sensory richness to revisit. A physical puzzle retains texture, weight, and the particular satisfaction of feeling a mechanism work. Even after you know the solution, the act of executing it engages your hands in a way that your brain finds rewarding. The journey remains interesting because the medium is richer than the information.

If you’re the kind of person who treats puzzles as problems to eliminate rather than experiences to repeat, you might actually get more value from a Yin Yang logic game that resets its challenge each time, or a memory match game that tests recall under fresh conditions.

Who Should Not Read Further

If you want puzzles to be simple entertainment — something to fidget with during conference calls — this framework is overkill. Skip it. Buy a spinner. No judgment.

If you’re looking for quick-fix brain training apps that promise cognitive improvement in five minutes a day, this approach is too slow and too physical for your goals.

And if you genuinely dislike the feeling of being stuck — not temporarily frustrated, but fundamentally uncomfortable with not knowing an answer — then mechanical puzzles may not be your medium. That discomfort is the point. It’s the space where principle, pattern, and number haven’t converged yet. Some people find that space energizing. Others find it unbearable. Both responses are valid.

Putting the Framework to Work

So how do you actually use principle, pattern, and number when facing a new puzzle?

Start with pattern. Before touching anything, look. Rotate the puzzle visually. Identify symmetries, anomalies, and joints. Notice which surfaces are smooth (designed to slide) and which are rough (designed to grip). Spend at least thirty seconds just observing.

Then consider principle. What type of mechanism are you likely dealing with? Interlocking? Sequential? Hidden pathway? Gravity-dependent? Your guess doesn’t need to be right — it needs to narrow the possibility space. The article on how collectors and casual solvers approach puzzles differently explores how experienced solvers develop this classification instinct over time.

Finally, engage number. Count the pieces. Count the visible joints. Estimate the minimum number of moves a solution might require. If you’re three moves in and the puzzle feels further from solved than when you started, you’ve likely chosen the wrong principle — go back and reassess.

This three-layer approach doesn’t guarantee fast solves. It guarantees smarter solves. And over time, it builds a kind of structured intuition that transfers beyond puzzles to mechanical repair, spatial planning, and any task where you need to understand how physical things interact.

3D Wooden Puzzle Treasure Box

This is where all three layers converge in a single object. The treasure box is a mechanical puzzle that actually stores things — you have to solve it to access the interior. The principle is sequential locking: multiple mechanisms must be released in order. The pattern is the visible surface, which offers subtle clues about which panels move and which are fixed. The number is the specific sequence of slides and rotations required. It makes a strong desk piece because it serves a real function beyond being a puzzle — and it gives visitors something to attempt when they’re sitting in your office.

View the 3D Wooden Puzzle Treasure Box →

Tian Zi Grid Lock Puzzle

A puzzle built around the Chinese character 田 (field), which is itself a grid — a visual representation of number embedded in language. The grid structure means every move affects multiple axes simultaneously, requiring you to hold several numerical relationships in mind at once. This is one of the best intermediate-level puzzles for training the number layer specifically, because the grid gives you a visible coordinate system to work with rather than forcing you to imagine one.

View the Tian Zi Grid Lock Puzzle →

For readers interested in the deeper history behind puzzle lock mechanisms and their relationship to traditional Chinese craftsmanship, our long-form piece on the carpenter who wrote the rules traces the design lineage from ancient workshop manuals to contemporary production.

The Half-Knowledge Advantage

The most useful insight from the old framework isn’t the three layers themselves. It’s the advice to stop at half.

Half-knowledge, in this context, isn’t ignorance. It’s deliberate incompleteness. It means understanding enough to navigate effectively while preserving enough uncertainty to remain engaged. In puzzle terms, it means you’ve solved enough to recognize categories and anticipate mechanisms, but you haven’t solved so many that every new puzzle feels like repetition.

The best puzzle collections are built on this principle. They include a range of difficulties and mechanism types — some you’ll solve in minutes, some that take days, and one or two that you may never fully crack. That last category isn’t a failure in the collection. It’s the most important piece. It’s the one that keeps your brain reaching.

A well-curated desk might include a quick-solve cast puzzle for fidgeting, a medium Luban lock for focused sessions, and something like a puzzle box that requires sustained effort across multiple sittings. The variety isn’t just about entertainment — it’s about keeping all three cognitive layers active and growing.

Records suggest that those who studied change at the deepest level eventually became so adept at prediction that they lost interest in action — why go outside if you already know you’ll trip? Why start a project if you can calculate its failure point? The warning isn’t about puzzles specifically. It’s about the relationship between understanding and engagement. Mastery without curiosity is a dead end.

So learn the principle. Read the pattern. Count the number. And then — deliberately, intentionally — leave room for the puzzle to be smarter than you.

That’s where the real training happens.