There is a particular moment — you have probably felt it — when your hands go still over a puzzle you cannot solve. The pieces are all there. The mechanism is sound. Nothing is missing except the one insight that would make everything fall into place. And the harder you push, the further away that insight retreats.

This is not a flaw in you. It is a feature of the puzzle. And it was understood, with remarkable precision, thousands of years before anyone coined the term “brain teaser.”

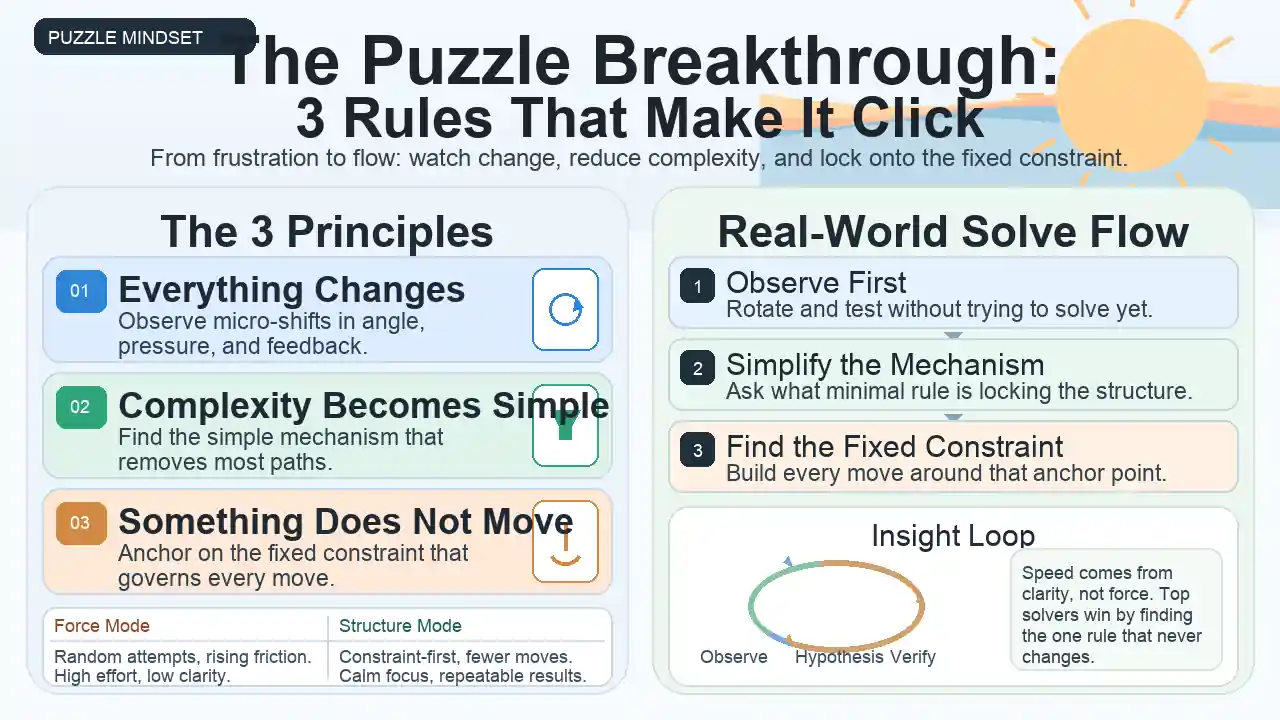

Old records describe a set of three governing principles that apply to every system of interlocking parts, every hidden mechanism, and every pattern that resists brute force. The principles are deceptively simple: everything changes, complexity reduces to simplicity, and beneath all motion sits something that does not move. Taken together, they form a framework that experienced puzzle solvers recognize immediately — even if they have never heard it stated so plainly.

What follows is a practical tour of those three ideas, tested against actual puzzles you can hold in your hands. No mysticism required. Just a willingness to stop forcing things.

The Calm Before the Click

Before the principles themselves, there is a prerequisite. Tradition names it with four qualities: purity, tranquility, precision, and subtlety. Stripped of ceremony, the idea is this — a scattered mind cannot solve anything worth solving.

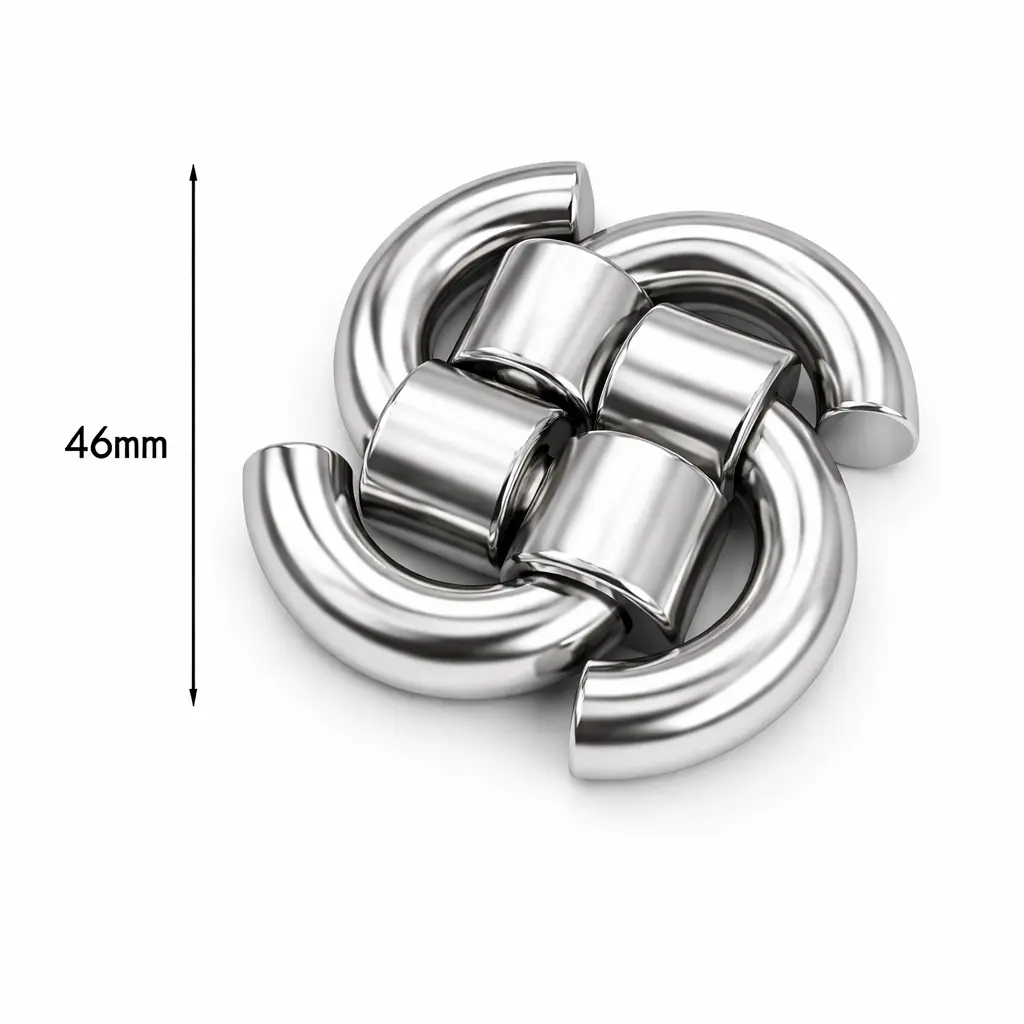

Anyone who has spent twenty minutes rotating a cast metal brain teaser knows the feeling. The first five minutes are confident. The next five are experimental. By minute fifteen, frustration sets in, and your movements become faster, sloppier, more random. That is exactly when you should stop.

The old teaching puts it bluntly: studying anything that involves hidden structure demands a cool head and precise thinking. One practitioner described reading difficult material at night and losing track of time entirely — solving one problem only to discover a new one behind it, then another behind that, until dawn arrived unnoticed. That kind of absorption is not willpower. It is what happens when the mind is genuinely still and genuinely engaged.

If you have ever explored what makes mechanical puzzles such a compelling collection, you know this state well. The best puzzles demand exactly this quality of attention — not aggressive focus, but calm precision.

This matters for a practical reason: the three principles that follow only work when the mind is quiet enough to notice them operating.

Principle One: Everything Changes

The first principle is the most obvious and the most frequently ignored. Everything changes. Every situation, every configuration, every assumption you carry into a puzzle — all of it shifts the moment you interact with it.

This sounds like philosophy-class material until you sit down with an interlocking puzzle and realize you have been holding it the same way for ten minutes. You assumed the entry point was on top. You assumed the first piece to move was the largest. You assumed symmetry meant equal force on both sides. None of those assumptions survived contact with the actual mechanism.

The principle of change does not mean chaos. It means attention. The skilled solver watches for what shifts — a slight wobble, a half-millimeter of give, a sound that changes when pressure is applied from a different angle. These micro-changes are the puzzle talking. Most people are too busy forcing their own solution to listen.

This is why experienced solvers often look like they are doing nothing. They rotate a piece slowly. They feel the weight distribution shift. They notice that the mechanism responds differently when warm from handling than when cold from sitting on a shelf. Everything changes, including the puzzle in your hands.

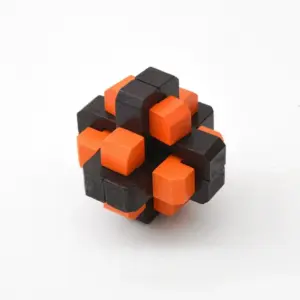

Cast Galaxy 4-Piece Silver

This cast metal brain teaser looks deceptively unified — four interlocked silver pieces that appear welded together. The solution requires recognizing that the relationship between the pieces changes depending on the axis of rotation you choose. There is no single “correct” orientation. Each rotation reveals a different possibility, and the solver who locks into one approach will stall completely. The limitation is real: this is not a puzzle for someone who wants a clear step-by-step path. It rewards spatial intuition and the willingness to let go of a failed hypothesis quickly.

- 4 interlocking cast metal pieces

- No tools required

- View the Cast Galaxy puzzle →

The principle of change also explains why the same puzzle can feel impossible on Monday and obvious on Wednesday. You changed. Your stress level is different, your grip pressure is different, your willingness to experiment is different. The puzzle did not get easier. You arrived in a different state, and that state happened to align with what the mechanism needed.

If you are drawn to puzzles where change is literally built into the form — spirals that unwind in unexpected directions, for instance — the 5-Piece Cast Spiral Metal Puzzle is a clean illustration. Five pieces. Multiple possible rotations. The solution path shifts depending on which piece you move first.

Principle Two: Complexity Becomes Simple

The second principle is the one that separates patient solvers from frustrated ones. Every complex system, once truly understood, reveals itself as simple.

This is not wishful thinking. It is an observable pattern in puzzle design. A six-piece interlocking burr puzzle looks impossible when assembled — dozens of potential movements, no visible entry point, no obvious sequence. But the solution is typically three to five moves. The complexity was always an illusion projected by the solver’s incomplete understanding.

Old teachings frame it as a philosophical contrast: when something exists but cannot be explained, the limitation lies in our experience, not in the thing itself. When an event occurs without apparent cause, the limitation lies in our wisdom, not in reality. Every phenomenon has a principle behind it. Find the principle, and what seemed mysterious becomes plain.

This is exactly what happens when you hear the satisfying click of a puzzle box opening. Seconds earlier, the mechanism was incomprehensible. Now, looking at the solved state, you wonder how you ever missed it. The path was always there. You simply could not see it yet.

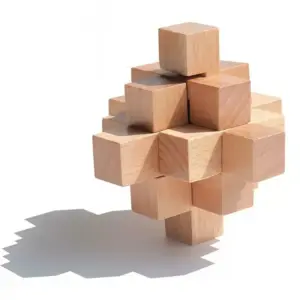

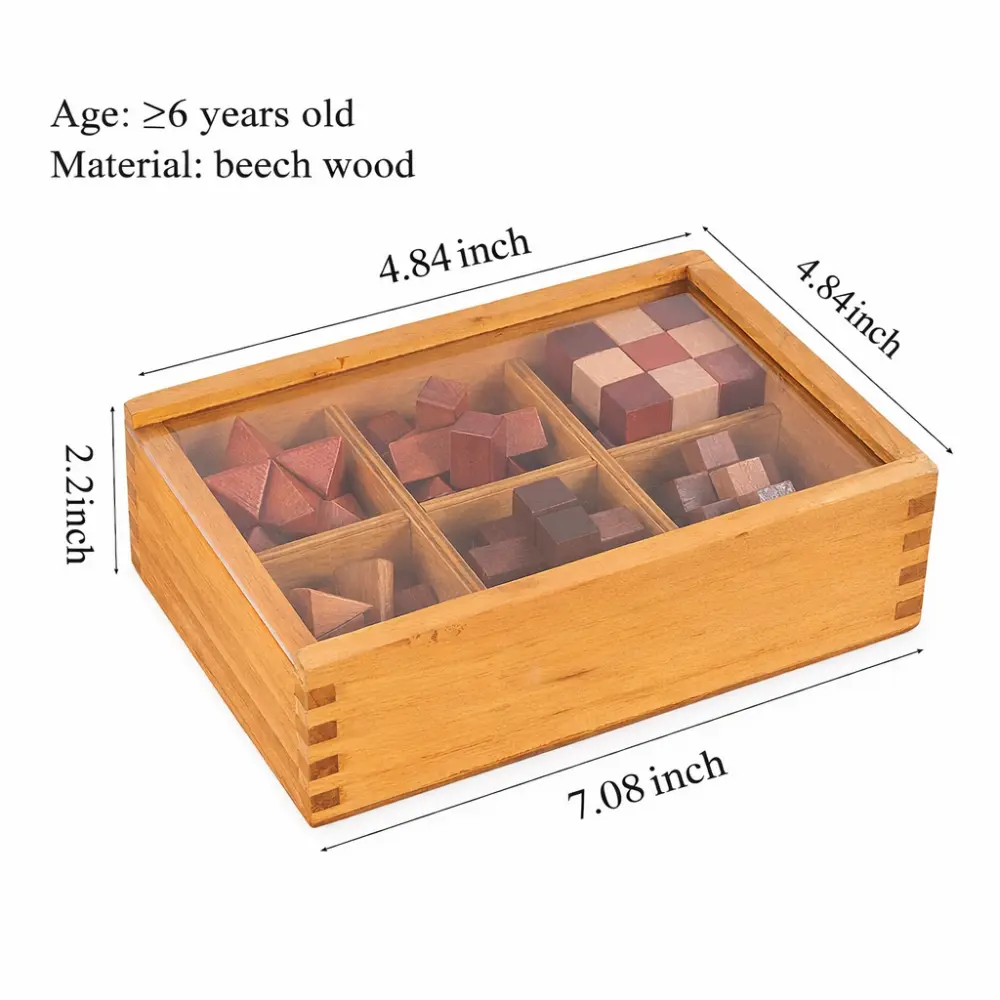

6-in-1 Wooden Brain Teaser Set

This set embodies the simplicity principle perfectly. Six different wooden puzzles, each looking like a tangled mess of interlocking pieces. Each one solves with a small number of precise moves — but discovering those moves requires understanding the underlying geometry rather than brute-forcing combinations. The set works as a training ground for exactly this skill: learning to see the simple structure hiding inside apparent complexity. Not ideal for anyone who wants a single long-session challenge — these are short puzzles, best solved one per sitting.

- 6 distinct wooden brain teasers

- Varied difficulty levels

- View the 6-in-1 Brain Teaser Set →

The practical takeaway is direct: when you are stuck on a puzzle, you are almost certainly overcomplicating it. The mechanism has a design logic. That logic is simpler than the shape of the object suggests. Your job is not to try every combination — your job is to find the principle that eliminates most combinations at once.

This is the thinking that guides a good approach to wooden brain teaser puzzles generally. The wood is not hiding a computer chip. There are no magnets. The solution is geometric, and geometry — once you see it — is clean.

Luban Lock Set 9-Piece

Few puzzle types demonstrate the simplicity principle more clearly than Luban locks. Nine pieces of wood, cut with precise notches, assembled into a solid form that appears to have no way in or out. But each Luban lock follows an internal logic dictated by the joinery itself. Find the key piece — the one that moves first — and the entire structure unfolds in sequence. It teaches a specific habit of mind: instead of asking “how do all these pieces fit together?” ask “which single piece holds everything in place?” That reframe is the simplicity principle in action.

- 9 interlocking wooden pieces

- Traditional joinery-based design

- View the Luban Lock Set →

The history behind Luban lock design stretches back centuries through the same carpentry tradition that produced some of the most sophisticated joinery in the world. If you want to understand how deeply the carpenter who wrote the rules influenced modern puzzle design, the connection becomes obvious once you handle a well-made interlocking set.

Principle Three: Something Does Not Move

This is the principle that takes the longest to grasp, and it is the one that matters most.

Amid all the change, amid the reduction of complexity to simplicity, there is something that does not change. Call it the core mechanism. Call it the design constraint. Call it the single rule that the puzzle builder could not violate without the puzzle ceasing to function.

In a well-designed trick box, every panel may slide, every surface may have a hidden seam — but the locking mechanism itself follows one inviolable rule. In a cast metal puzzle, the pieces may rotate freely in multiple axes, but the solution depends on one specific geometric relationship that never changes regardless of orientation.

The old teaching states it plainly: philosophers call this the fundamental substance. Scientists call it function. Whatever name you give it, this is the thing that remains constant while everything else transforms around it.

For puzzle solvers, this translates to a critical skill: identifying the constraint. What cannot change about this puzzle? What is structurally fixed? That fixed point is your anchor. Everything else — the rotations, the sliding panels, the red herrings — is noise. The signal is the constraint.

The Barrel Luban Lock

This puzzle is a masterclass in the constancy principle. Shaped like a small barrel, it consists of wooden staves held together by internal notches. Every piece appears identical. Nothing suggests a starting point. But there is one piece — always one — whose geometry differs slightly from the rest. That single difference is the constant around which the entire puzzle was designed. Remove that piece, and the rest release in sequence. Miss it, and you can manipulate the barrel for hours without progress. The lesson is blunt: find what does not change, and you have found the solution.

- Barrel-shaped interlocking wood puzzle

- Traditional Luban lock mechanism

- View The Barrel Luban Lock →

This principle explains why some people solve difficult puzzles quickly and others do not. Speed has little to do with it. The fast solver is not trying more combinations per minute. The fast solver is looking for what remains fixed — the constraint that governs all possible movements. Once found, the solution follows logically.

It also explains a peculiar phenomenon: the solver who walks away from a puzzle and returns to solve it in seconds. What changed was not the puzzle. What changed was the solver’s willingness to stop looking at the moving parts and start looking for the still point.

If you enjoy puzzles that make this principle tactile — where finding the fixed element is literally the mechanism — traditional wooden locking puzzles offer some of the clearest examples available.

When the Principles Fail (Or Rather, When You Do)

There is a recorded warning about these principles. The tradition acknowledges that knowledge of pattern, structure, and hidden mechanism can be misapplied. A person who understands how locks work can open doors they should not open. A person who understands influence can manipulate rather than persuade.

The puzzle-world equivalent is the solver who immediately looks up the solution. The mechanism is defeated, but nothing was learned. The three principles remain untested. The patience, the calm focus, the moment of genuine insight — all of it was skipped.

This is worth stating directly: if you are the kind of person who checks the answer within five minutes, most puzzles above entry level will disappoint you. Not because they are too hard, but because you will never experience the state of mind that makes them rewarding. The old practitioners called this state “so absorbed that spring passes without notice.” Modern psychologists call it flow. Either way, you cannot reach it in a hurry.

Who Should Probably Skip This Entire Approach

Not everyone needs puzzles to teach patience. If you already have a meditation practice, a martial art, a musical instrument, or any other discipline that demands sustained focused attention, you may find puzzle solving redundant as a mindfulness tool. The principles still apply — they are useful for solving the puzzles faster — but the personal development angle may not add much for you.

Similarly, if you are looking for party entertainment or quick fidget toys, the puzzles discussed here will frustrate rather than satisfy. They are designed for sustained engagement, not casual distraction. A puzzle box for family game night is a different category entirely from a Luban lock you work on alone over several evenings.

Know what you want before you buy.

Applying the Principles: A Practical Sequence

Here is how the three principles work together when you actually pick up a puzzle:

Step one (Change): Handle the puzzle without trying to solve it. Rotate it. Feel the weight. Notice what moves and what does not. Pay attention to how the mechanism responds differently to different types of input — pressure, rotation, lateral sliding. You are not solving yet. You are listening.

Step two (Simplicity): Ask yourself: what is the simplest possible mechanism that could hold this together? Not the most clever, not the most complex — the simplest. Most puzzle designs are more constrained than they appear. A six-piece interlocking puzzle probably has one key piece. A trick box probably has one primary locking mechanism. Find it.

Step three (Constancy): Identify the fixed point. What cannot move? What is the structural anchor? Every other piece exists in relationship to this anchor. Once you find it, the solution sequence usually becomes obvious — or at least reduces from hundreds of possibilities to a manageable few.

The Tian Zi Grid Lock Puzzle is a good test case for this sequence. Its grid-based design appears to offer many possible entry points, but the internal structure follows a single constraint that governs all movement. Apply the three steps and the puzzle typically opens faster than expected.

For those who want to test their spatial reasoning with an interactive warm-up, the Yin Yang logic game offers a digital counterpart to this same balance of structure and adaptability. Sometimes a few minutes of pattern-based thinking primes the mind for physical puzzle work.

The Clock Problem (Or: Patience Has a Shape)

There is a reason clocks appear so frequently in puzzle design. Time is the medium in which all three principles operate. Change happens across time. Simplicity is revealed when you give yourself enough time to stop overcomplicating. Constancy is what survives when time strips away everything temporary.

3D Wooden Puzzle Clock DIY Kit

Building a mechanical clock from wooden pieces is a different kind of puzzle experience. The solution is predetermined — you follow assembly steps — but the understanding is not. Watching gears mesh, seeing how one rotation becomes a different rotation through a ratio change, feeling the mechanism’s rhythm emerge from individual parts — this is the simplicity principle made tangible. You start with a pile of laser-cut pieces and end with a working clock that you genuinely understand. The patience required is real: this is not a thirty-minute project.

- 28 laser-cut wooden pieces

- Functional clock mechanism after assembly

- View the 3D Wooden Puzzle Clock →

The clock also illustrates something the tradition emphasizes about the principle of constancy: the unchanging thing is not the pieces. The pieces wear down, warp, and eventually break. The unchanging thing is the principle that makes the clock keep time — the mathematical relationship between gears. Replace every piece, and the clock still works, because the principle was never in the wood. It was in the design.

This is the same insight that drives the craft of puzzle design through the lens of mechanical engineering. The best puzzles are not clever shapes. They are clever constraints expressed through shape.

Metal, Wood, and the Materials of Patience

Material matters more than most puzzle buyers realize, and it matters for reasons the three principles predict.

Metal puzzles embody the change principle. Cast zinc alloy shifts subtly with temperature. Grip pressure varies. The interaction between solver and puzzle is dynamic and constantly adjusting. The Interlocking Metal Disk Puzzle is a clear example — its solution depends on precise alignment that feels different every time you pick it up, because your hands are never in exactly the same state twice.

Wooden puzzles embody the simplicity principle. Wood joinery is inherently geometric. There are no springs, no magnets, no hidden electronics. The mechanism is the shape of the wood itself. When the traditional craft behind these designs traces its roots to the ancient carpentry text behind modern puzzles, you begin to understand why simplicity is not a limitation but a design philosophy.

Crystal and glass puzzles embody the constancy principle in a surprisingly literal way. Transparent material lets you see through to the structure. The fixed point is visible. The 12-Piece Crystal Luban Lock Set makes the internal geometry visible in a way that opaque wood cannot, which changes the solving experience fundamentally — you can see the constraint, but seeing it and understanding it are not the same thing.

The Portable Version

Not every puzzle sits on a desk. Some of the best applications of these principles happen in your pocket.

The Antique Bronze Metal Keyring Puzzle is small enough to carry daily and complex enough to resist casual fiddling. It is the kind of object that teaches the change principle through repetition — you solve it, reassemble it, and solve it again, and the experience is slightly different each time because your muscle memory and your conscious strategy are developing at different rates.

Portable puzzles also test an underrated skill: solving in public, surrounded by distraction. The calm-mind prerequisite becomes harder to maintain in a coffee shop or airport lounge. This is where the “pure and tranquil” teaching becomes genuinely practical rather than aspirational. Can you find that still point amid noise? The puzzle in your pocket answers the question honestly.

If you are exploring the full range of what carry-friendly brain teasers offer, the curated guide to puzzle locks and their mechanisms covers the portable end of the spectrum in useful detail.

What Patience Actually Produces

The three principles are not self-help advice. They are structural observations about how hidden mechanisms work. But applied consistently — across dozens of puzzles, across months of practice — they produce something worth naming.

You develop a tolerance for not knowing. You learn to sit with an unsolved problem without anxiety, because you trust that the mechanism has a logic and that logic will eventually reveal itself if you stay attentive. This is not optimism. It is pattern recognition applied to your own cognitive process.

Experienced puzzle solvers report a specific kind of calm that non-solvers find difficult to understand. It is not relaxation exactly — the mind is active and engaged. It is closer to what musicians describe during improvisation or what athletes describe during a long-distance race. The body is working, the mind is clear, and the two are synchronized.

That state has value beyond the puzzle table. The tradition noted this centuries ago: one who has internalized these three principles can navigate complex situations — professional, personal, strategic — with less reactive emotion and more structural clarity. The puzzle is practice. The principle is the point.

For a tangible entry into this practice, the 3D Wooden Puzzle Treasure Box offers something most puzzles do not: a functional endpoint. Solve it, and you have a working box that stores small objects. The puzzle becomes furniture. The patience becomes a physical thing you keep on your desk.

Where to Start (And Where Not To)

If the three principles resonate, start with a wooden interlocking puzzle in the beginner-to-intermediate range. The feedback is immediate, the mechanisms are honest, and the solving time is measured in minutes to hours rather than days. The full guide to traditional wooden puzzles offers a solid orientation.

Do not start with the hardest thing available. The principles need room to develop, and a puzzle that defeats you completely before you have built any pattern recognition is not training patience — it is testing endurance. Those are different skills.

Build from simple interlocking puzzles to Luban locks to trick boxes to cast metal challenges. Each step adds complexity, and by the time you reach the harder end, the three principles will be operating more or less automatically. You will recognize change as it happens. You will look for simplicity before you look for cleverness. You will hunt for the fixed point before you try any combination.

That is not mystical insight. It is practical skill, built through repetition, expressed through calm hands on well-made puzzles.

And one day — probably on a Wednesday, probably when you are not even thinking about it — the piece that would not move will move. Not because you forced it. Because you finally stopped forcing and let the principle do the work.